Aurich Lawson

Anyone with a passing interest in retro games knows the bulk of classic video game history is effectively “out of print,” with legitimate copies limited to defunct hardware platforms and secondhand physical copies (if you’re lucky). Now, in a first-of-its-kind study, the Video Game History Foundation has determined the full extent of this issue, finding that a full 87 percent of games released in the US before 2010 are no longer commercially available.

This vast expanse of out-of-print games isn’t exactly “lost,” of course; libraries, archives, and even software pirates have helped ensure the games will continue to be accessible in some form. But the VGHF argues persuasively that the poor market availability of reissued games highlights how the game industry is not doing a sufficient job of preserving access to its own history.

“The industry has done a great job re-commercializing a wide catalog of [popular] titles, but for the vast majority of games, we can’t rely on the commercial market to solve this,” VGHF Library Director and study author Phil Salvador told Ars in a recent interview. “We need to give libraries and archives more tools to get the job done.”

What’s available?

The VGHF study analyzed a random sample of 1,500 titles pulled from MobyGames’ extensive, crowdsourced database of over 27,000 games released in the US before 2010 (roughly when increasing digital releases and backward compatibility changed the modern continuing access equation). The study also took a more in-depth look at a handful of classic platforms, from the Commodore 64 (95.5 percent of titles currently out of print) to the PlayStation 2 (88 percent out of print).

The 13 percent of legacy games that are currently in print is comparable to the availability of much older, pre-World War II music recordings (10 percent or less in print), a comparison that Salvador says shows just how behind the gaming market is on this score. “Video games have historically been treated as disposable toys,” he told Ars. “Commercial game emulation has been underdeveloped as long as games have been falling through the cracks legally. We’re all still playing catch-up taking this medium seriously, and unfortunately, these are the long-term effects we’re dealing with.”

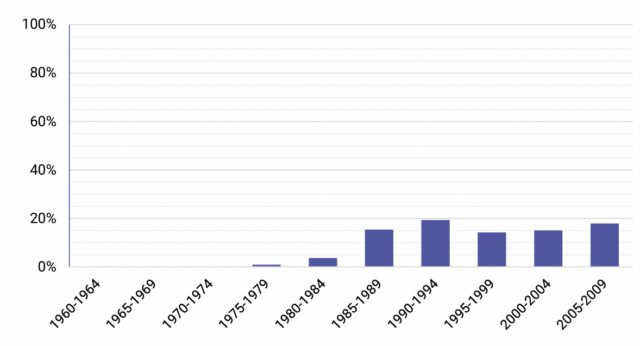

Beyond the headline numbers, the availability of legacy games varies greatly across different eras of gaming’s short history. A paltry 2.6 percent of games released in or before 1984 are in print, compared to 16.5 percent of games released since then.

That reflects the limited market value of the industry’s oldest games, which Salvador acknowledges are “a little archaic and not especially exciting from a commercial perspective.” But these 30-plus-year-old titles are also more likely to interest game researchers and developers looking into the influences that have driven the industry’s evolution over time.

“It’s not the obligation of game publishers to keep games in print,” Salvador told Ars. “But it also means we shouldn’t expect the commercial market to solve that problem [of access].”

Why is this a problem?

To an average gamer, the fact that most classic games are no longer for sale might not be a practical concern. Piracy groups have gone to great lengths to ensure that entire platform catalogs have been ripped and preserved, with only a few unemulated exceptions. Apart from that, many games are available relatively cheaply on the secondhand market (if you have working hardware) or through institutional archives like Standford University’s Cabrinety Collection.

For researchers, though, these solutions are imperfect. A professor assigning students a game to study, for instance, might find their university department is uncomfortable leaning on the “fair use” legal argument that would be needed to distribute a pirated copy. For these kinds of reasons, Salvador acknowledges piracy in the study as “often a last resort and necessity for proper study.”

And beyond academia, piracy isn’t necessarily a mainstream-ready access solution. “Those of us already ‘in the know’ are set for life. My ROMs are never going away,” VGHF founder and Executive Director Frank Cifaldi tweeted. “But I love video game history and I want it to be for everyone, not just the software-literate nerds. I want to see old games inspiring the weird artists of the future.”