The Pakistani establishment “has tended to prefer coalitions and if, as is being reported, it is managing these elections like before, we may yet see another coalition emerge from these elections,” said Husain Haqqani, a former Pakistani ambassador who is currently a senior fellow at the Anwar Gargash Diplomatic Academy in Abu Dhabi.

More than 128 million Pakistanis are eligible to cast ballots for candidates contesting elections for the National Assembly and one of the country’s four provincial assemblies.

However, the overall result will hinge on the outcome of the elections in eastern Punjab province, which is home to slightly more than half the country’s population and a matching number of National Assembly seats.

Pakistan struggles to secure IMF bailout as military intervention rears its head

Pakistan struggles to secure IMF bailout as military intervention rears its head

Punjab is also Khan’s home province, as well Nawaz Sharif – another former prime minister, and the leading recruitment ground for the military.

“Pakistan suffers from majoritarian tyranny in the sense that out of the total four of the federating units, one federating unit is population wise bigger than the other three,” said former senator Afrasiab Khattak.

“So the party that wins Punjab forms the government at the federal level.”

This has forced its candidates to contest the general election as independents, each assigned a different symbol, making it difficult for many PTI voters to identify their party’s candidate.

Resultantly, voter turnout, which averaged about 50 per cent in national polls in 2008, 2013 and 2018, could be on the low side, analysts said.

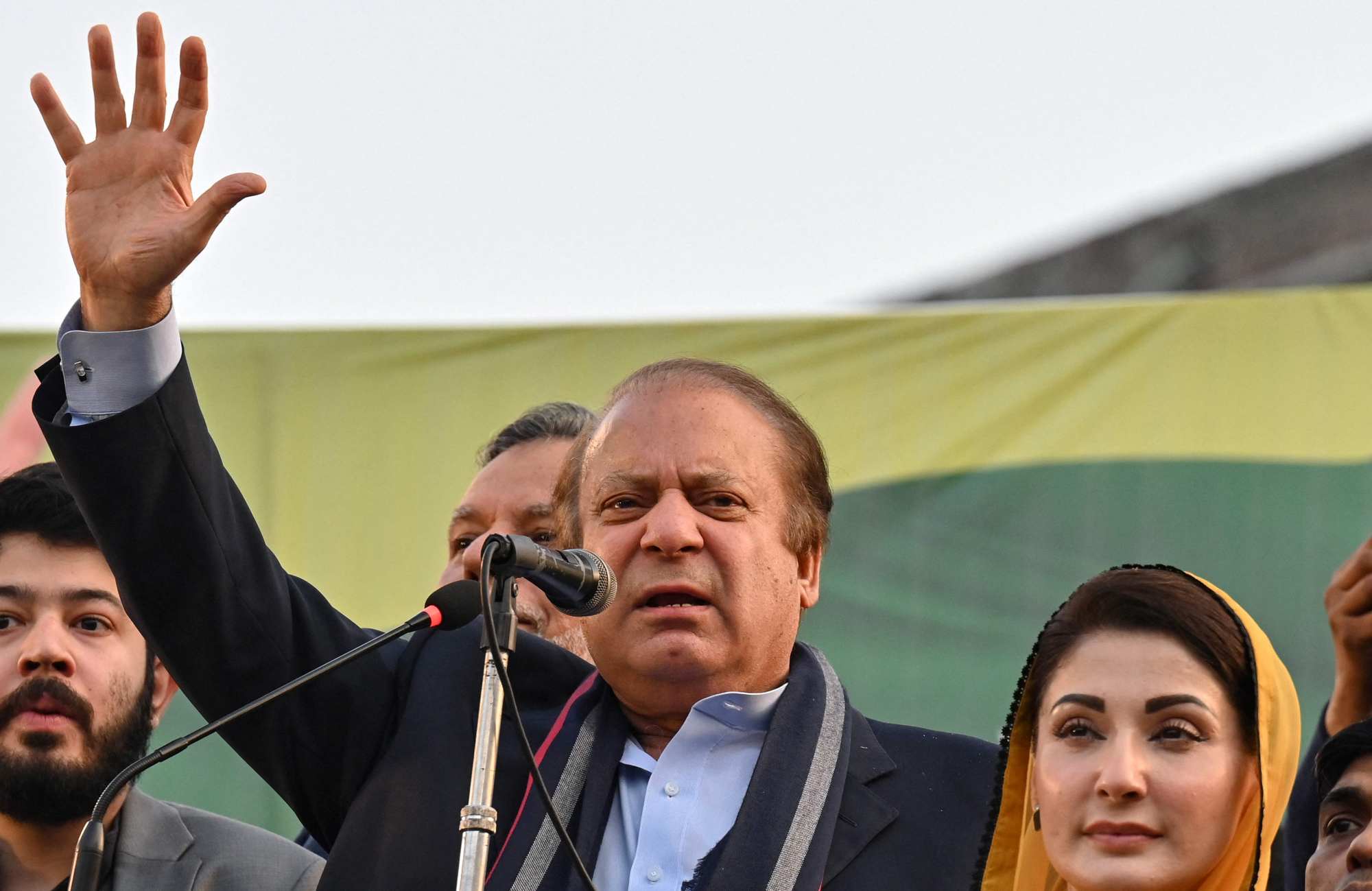

This makes the formation of another weak multiparty coalition government, led by PML-N chief Sharif, the most likely outcome.

Sharif is bidding to become Pakistan’s prime minister for an unprecedented fourth time, having previously been elected in 1990, 1997 and 2013.

On each occasion, he was removed from power by the military-led establishment, and was twice imprisoned on corruption charges that ultimately failed to stick – most recently in June 2018, a month before the election that ushered Khan and the PTI into power.

With their circumstances now reversed, the credibility of Pakistan’s February 8 election and the shaky coalition administration it is expected to yield has already been greatly undermined.

Only credible elections, by representing popular aspirations, can bring stability, rigged elections lead to instability

“The way judicial and administrative organs of the state have been used to make sure that the PTI doesn’t win the election, the elections will have a credibility problem,” said Khattak, who is a ranking member of the National Democratic Movement, an ethnic Pashtun nationalist party opposed to the political dominance of Pakistan’s military.

“Only credible elections, by representing popular aspirations, can bring stability,” he said, adding that “rigged elections lead to instability”.

Analysts said this expected outcome would further empower the Pakistani establishment, with no stability in sight.

Each one of Pakistan’s 11 previous general elections “have been mired in controversy and the 12th one scheduled for February 8 is not different”, said Haqqani, who is also the author of Reimagining Pakistan: Transforming A Dysfunctional Nuclear State.

Until all Pakistani political actors “agree on political rules of the game, instability is unavoidable”, he said, adding: “There will be a ruling party or coalition, and there will be an aggrieved party trying to pull it down”.

“Add to that” the US$78 billion of foreign debt coming due between now and 2026, and the resurgent threat of terrorism to Pakistan, and “the reason for anticipating uncertainty becomes obvious”, Haqqani said.

Khattak said Pakistan underwent a “creeping coup”, beginning in 2014 and climaxing in 2018, leading to a military-dominated elected government under what’s commonly referred to as “the hybrid system”.

Pakistan, Iran military chiefs unite to ‘eradicate terrorism’, stop militants

Pakistan, Iran military chiefs unite to ‘eradicate terrorism’, stop militants

Pakistan’s democracy was “further militarised” by the coalition administration led by the PML-N which replaced Khan after he was removed in an April 2022 no confidence vote.

“So it is now a hybrid-plus system,” said Khattak, who predicted “another round of civil-military squabbles” during the tenure of Pakistan’s next government.

Meanwhile, Pakistan “has had its hands full with a polycrisis at home” that is related to its tensions with the Taliban-led regime in Afghanistan and rising levels of terrorism by Pakistani Taliban and ethnic Baloch insurgents, he said.

Forthcoming elections in Pakistan and India “mean both countries will be busy with political consolidation and governance planning” in the first half of the year.

In the second half of 2024, “we might observe some thaws in the relationship” including diplomatic ties, trade, and travel corridors, Lalwani speculated.

Haqqani said India would “continue with economic growth” after its elections, while Pakistan would “continue to be mired in political and ideological squabbles”.

The United States will continue to see India as an economic opportunity and will view Pakistan as “a problem to be managed”, while China will “remain Pakistan’s backer of last resort” because of China’s growing competition with India, Haqqani said.