VHP is one of several Hindu nationalist groups who detest anything to do with the Mughals, who ruled over a huge swathe of the Indian subcontinent for several centuries before the arrival of the British and are regarded by hardliners as having enslaved the Hindu majority.

2 lions in India named after Hindu deity and Muslim emperor spark court petition

2 lions in India named after Hindu deity and Muslim emperor spark court petition

In its petition, VHP, which has ties with Modi’s ruling BJP, is demanding action against the North Bengal Wild Animals Park in Siliguru, West Bengal.

“Sita cannot stay with the Mughal emperor Akbar,” VHP leader Anup Mondal told reporters in Kolkata on Sunday.

The VHP also objects to the lioness being named after a Hindu goddess. “Such naming of animals after the name of religious deities is very much sacrilegious and tantamount to blasphemy,” said Dulal Chandra Roy, another VHP official.

Alarmed at the protest, zoo officials have separated the two lions and transferred them to a park in Tripura Zoo in the country’s northeast.

Critics say the case is yet another example of how the Modi government has presided over rising religious intolerance and provocative demands for censorship in India, a Hindu-majority country with the world’s largest Muslim minority population at some 200 million.

“Members of the ruling party often talk about Hindu slavery under the Mughals and express disgust for anything to do with Muslim culture. This encourages Hindu extremists to keep the pot boiling with confected indignation,” veteran columnist Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jnr told This Week in Asia.

Love Jihad: a Muslim bogeyman in Indian states’ interfaith marriage laws

Love Jihad: a Muslim bogeyman in Indian states’ interfaith marriage laws

Hardline Hindu groups have often been quick to invoke these laws and file police complaints as a way of removing any content they dislike.

The 32-year-old had been regularly heckled at his shows and online by Hindu radicals who accused him, without evidence, of insulting their deities. He was eventually forced to give up his career as a comedian owing to threats of violence that repeatedly saw organisers cancel his gigs.

“I’m done … hate won”, he announced on Instagram after receiving an average of 50 threats a day.

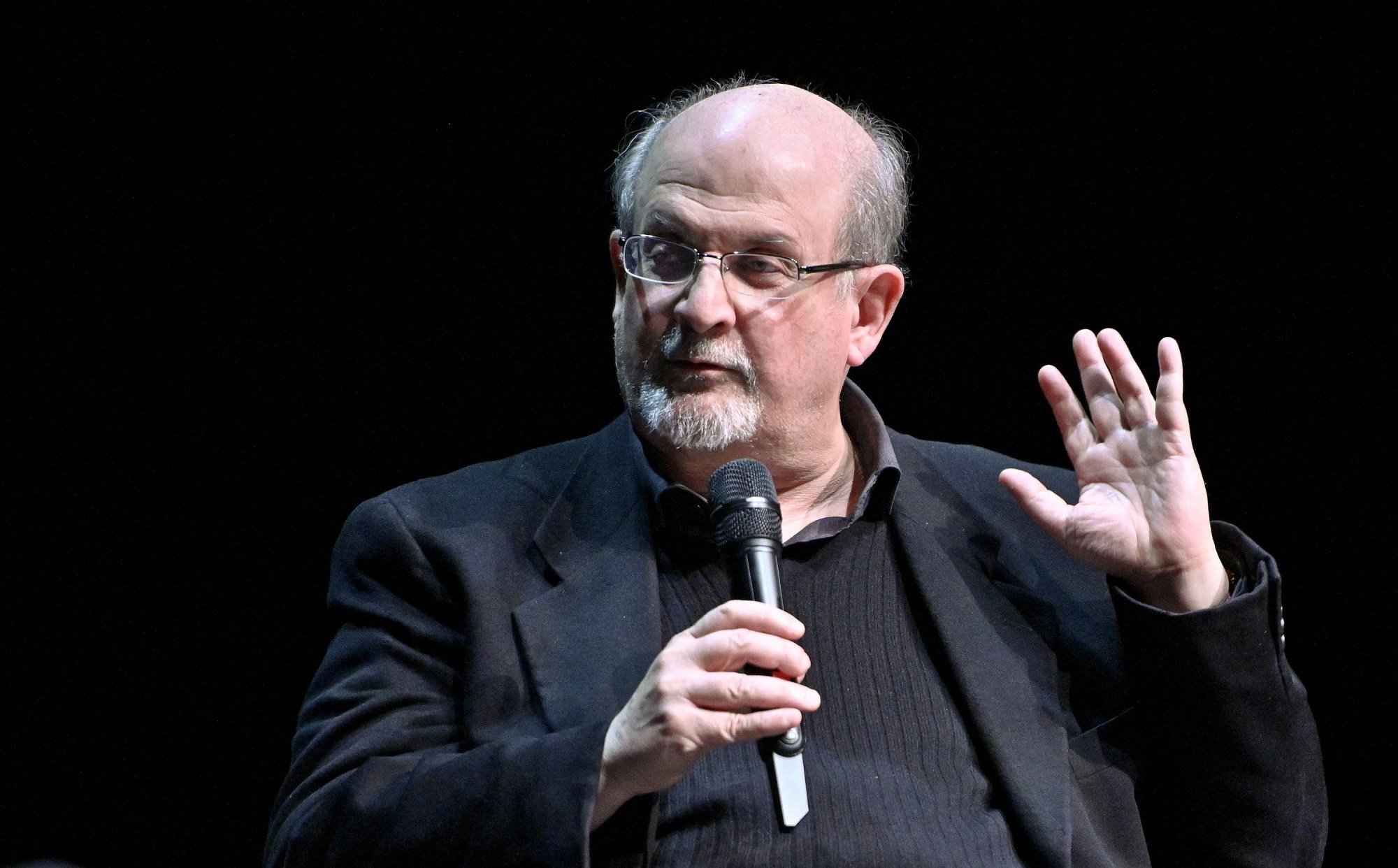

“The government then was so sympathetic to Muslim sentiments that the book was banned at once. Now it’s our turn to protect our religion,” 42-year-old Sudhir Narang, a VHP sympathiser in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, told This Week in Asia.

Narang added that when Rushdie was planning to attend a literary festival in Jaipur in 2012, Muslim groups had demanded that Indian authorities deny him a visa. In the end, the author decided not to attend and spoke via a video link instead.

In India, chorus of anti-Muslim hatred grows louder with rise of Hindutva pop

In India, chorus of anti-Muslim hatred grows louder with rise of Hindutva pop

“As I recall, no liberals or lefties spoke out against the unreasonableness of that demand but somehow Hindu demands are always extremist,” Narang said.

As a result of these campaigns by extremist Hindu groups and individuals, creatives in India have increasingly chosen to self-censor their works to avoid any potential confrontations.

A relatively well-known Bollywood director, who declined to be named, told This Week in Asia that the possibility of ending up in the cross hairs of such groups was scary.

“It might be a 20-second scene, a sentence or two and that will be two years’ work down the drain if it has to be withdrawn. It’s not worth it [to antagonise the radical Hindu groups],” he said.