A graduate from Boston University, Downey is a self-educated wine expert and one of the industry’s best known fraud detectors. Her knowledge is vast and diverse: she learned about glass from American artist Dale Chihuly and paper from a conservationist at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. She has worked in restaurants and auction houses.

Eventually, her name reached the ears of American law enforcers – including the FBI and the US Department of Justice – who sought her expertise in cracking two infamous cases involving Rudy Kurniawan, who sold fake wines for US$1.3 million; and Rodenstock.

In 2005, Downey started her own consultancy – Chai Consulting – and online hub Winefraud to raise awareness of counterfeits. She now has an extensive network of authenticators around the world that she’s looking to expand. She will be hosting authentication workshops at the Grand Hyatt Hong Kong hotel for wine on March 2 and 3, and for whisky on March 4.

Sour grapes: Indonesian wine fraudster Rudy Kurniawan deported from US

Sour grapes: Indonesian wine fraudster Rudy Kurniawan deported from US

According to a study into illicit alcohol in Latin American, African and Eastern European countries by Euromonitor International in 2018, an estimated 25.8 per cent of the 42.3 million hectolitres (930.4 million gallons) of alcohol consumed annually was illicit; 24 per cent of that is categorised as counterfeit and unregistered brands. The study concluded that the illicit alcohol trade generated US$19.4 billion in black market revenue.

The internet is also to blame for an uptick in wine crimes. “Before, customers would go through a wine journey that doesn’t dive straight right into DRC Montrachet,” says Downey. Domaine de la Romanee-Conti Montrachet Grand Cru is valued on average at US12,780 a bottle.

The prominence of online shopping and rise in global wealth, however, means enthusiasts have direct access to fine and rare bottles; this has also “opened up an opportunity where you have a whole lot of ignorance and a whole lot of money,” she says. “This is the perfect set up for fraud to happen.”

She’s found DRC Montrachet in banded boxes – a kind of packaging designed for supposed security – that were later proved to be fakes; she also uncovered a 1982 Chateau Mouton Rothschild Bordeaux, which fetches more than US$1,500 a bottle, filled with rose.

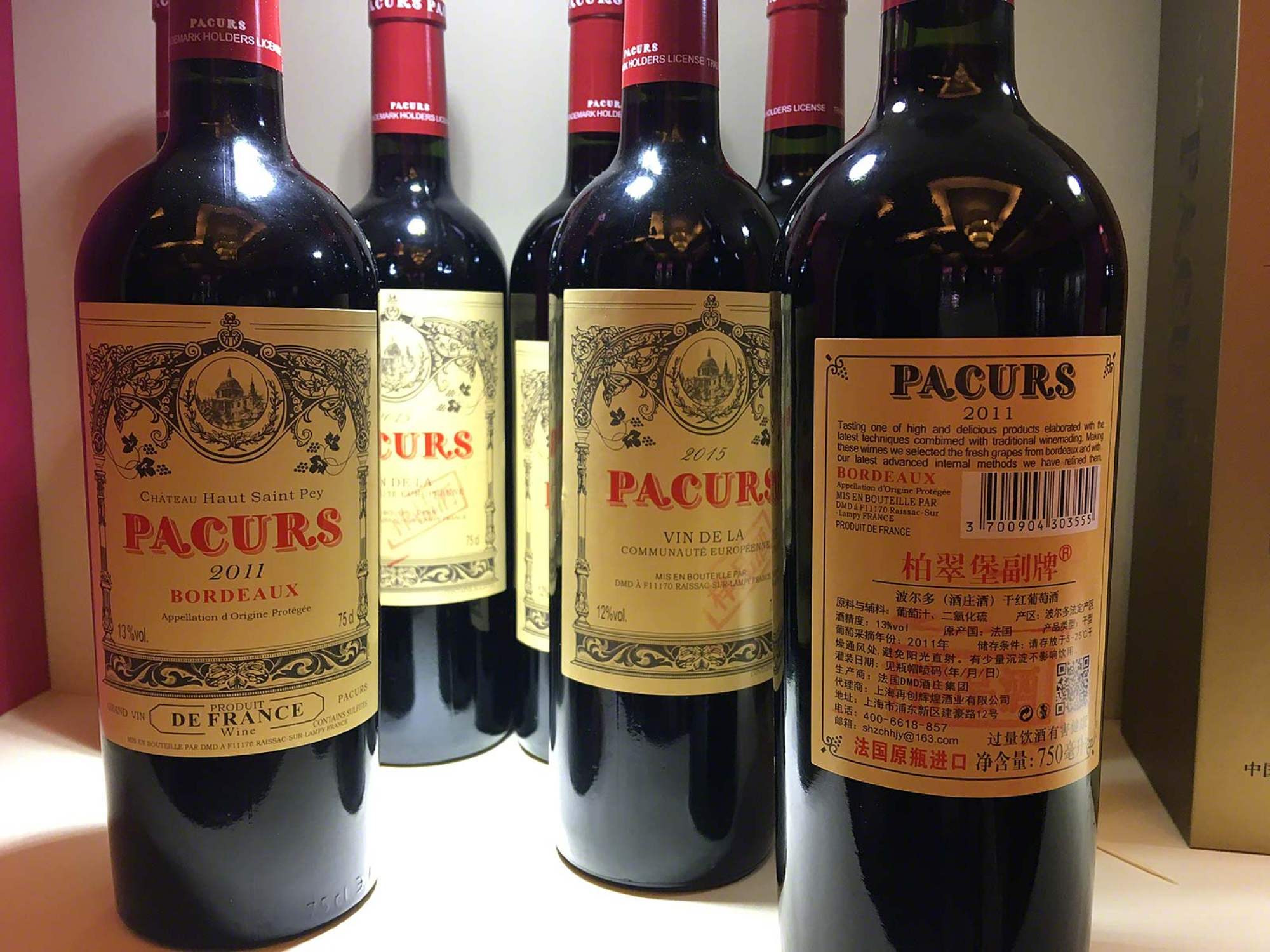

As part of her process, she rarely cuts the capsule – the protective covering around the cork – except when it comes to Henri Jayer wines, as she claims “there’s just no other way to verify it”. Instead, she looks for other visual cues, such as spelling and punctuation mistakes on labels, the integrity of the cork, as well as era-appropriate glass, ink or paper.

Fake wines are also not exclusive to the upper echelons of society: in 2010, bottles of counterfeit Louis Jadot Pouilly-Fuissé were found at UK supermarket chain Tesco, which sold for £5 (US$6.34), reduced from £14.49.

A year later, the UK saw another influx of fake Yellowtail bottles that were reported to taste and look questionable. Though with varying scrupulousness, counterfeit wines of different price points are coming from and showing up everywhere.

Aside from financial loss and tarnished reputations – whether of the buyer, brand or broker – Downey says wine fraud is rapidly becoming a cash cow for organised crime syndicates, with fakes coming out of war-torn zones like Syria. Compared to conventional crimes like drug or human trafficking, wine fraud poses a much lower risk, thanks mostly to an opaque supply chain that allows for anonymity, non-consequential sentences and trusting consumers who don’t bother checking, especially collectors who buy expensive wines for bragging rights over enjoyment.

Producers have counteracted with anti-fraud features – QR codes, invisible ink, special capsules – which Downey calls “cosmetic marketing schemes”. Not only can they be counterfeited, but high-end bottles are rarely exchanged in person.

“Very few people drop 50 grand to buy Mouton Rothschild in a store. They either buy online or in response to an email, meaning they’re not there to inspect the bottle. Once they can see the bottle, it’s too late – it’s no longer an investment, it’s a problem,” she says.

“If it’s a non-cosmetic antifraud, then who’s going to know to look for it? Producers are extremely secretive with this stuff, so how many people will actually take their bottle of Petrus back to the chateau first to see if it’s real? Not to mention that they aren’t going to open the door for you.”

So aside from expanding her team of authenticators – who are sometimes called on a job just days in advance – Downey has founded the Chai Wine Vault, a blockchain-oriented security system in which a chip is inserted within the capsule with a scannable QR code.

Photographs, serial numbers and condition reports of every bottle are uploaded onto a blockchain digital ledger to be recorded at every distribution point, so the data is transparent to both buyer (for ensuring provenance and assurance) and the producers, who can then track their real consumers and get a chance to interact with them.

Her cyber vault also welcomes bottles from the secondary market – a rarity in blockchain services – on the condition that suppliers can offer proof of provenance for the bottles that undergo authentication by her team.

“Ultimately, I want to combat fraud by bringing transparency into the supply chain and empowering producers not just in the secondary market, but by offering them direct communication to people who are drinking their wines and not brokers looking to earn a quick buck,” she says.

At the March workshops, participants can expect a thorough dive into fraud, types of counterfeits and an introduction to authentication including her famous, 16 points of inspection on a bottle. Her seminars are usually capped at 20 attendees, who are vetted to weed out scammers looking to gain intel on how to improve their counterfeit alcohol. Prospective participants are asked to provide their work history and two professional references if they wish to attend workshops.

In the end, Downey sees her work as a valuable service. “We need people to be educated, whether they’re working in the wine industry or for self-enjoyment,” she says.