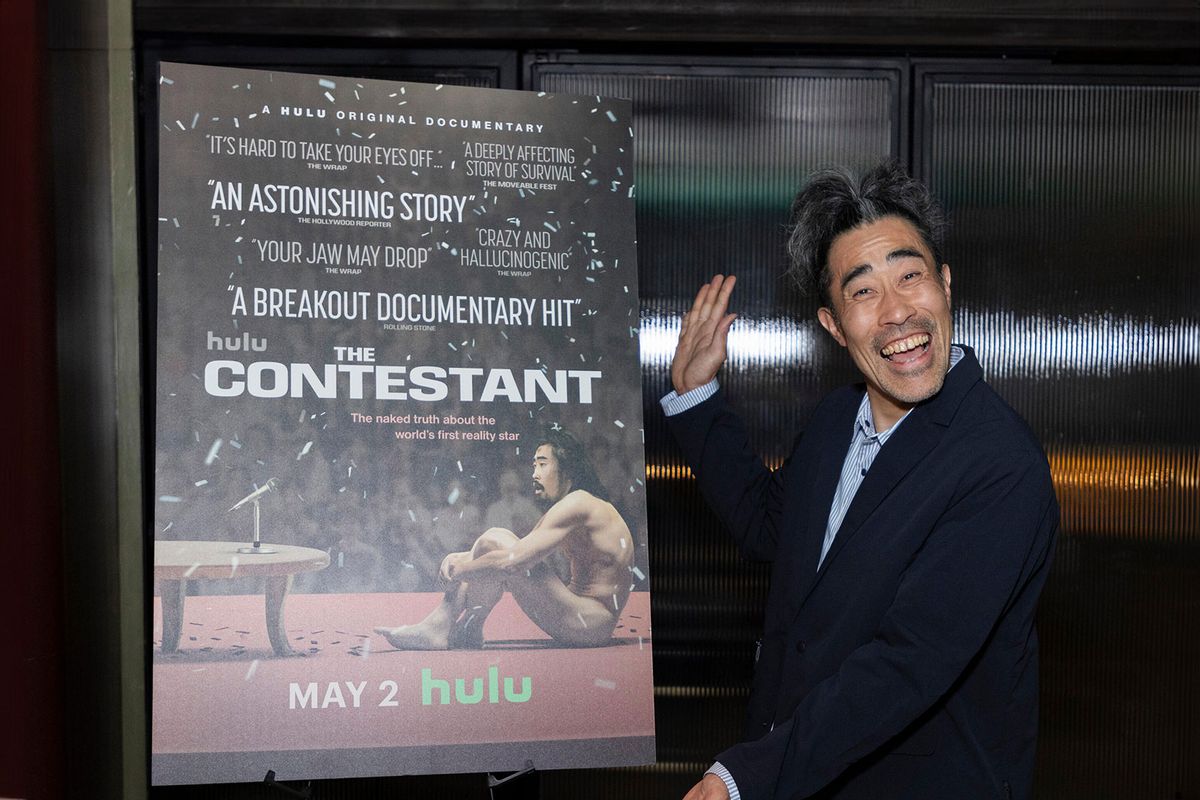

Clair Titley never set out to have “The Contestant” explore the origins of reality television. Though some critics have opined in favor of the importance of such a lens where the recently released Hulu documentary is concerned, she didn’t endeavor to provide a thorough examination of the ethics of reality media. Instead, she wanted to give one man “the space to just really unravel all those thoughts.”

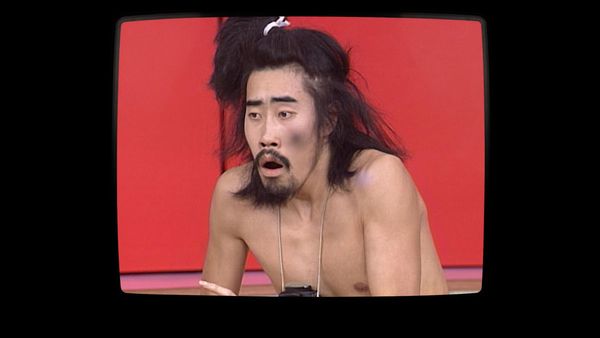

“The Contestant” chronicles the 15 months that 22-year-old Tomoaki Hamatsu, better known as Nasubi, spent naked in isolation in 1998 as a willing participant on a popular Japanese reality show, “Susunu! Denpa Shonen.” Nasubi’s ordeal, which saw him submit to magazine sweepstakes to obtain food, was broadcast to millions, unbeknownst to him until his challenge ended.

“He would be paranoid that people were filming him.”

Though Nasubi did not retain any editorial control in the production of the documentary, he collaborated heavily with Titley, lending his testimony and thoughts to its creation. After all, “The Contestant” is about Nasubi’s experience, tracing not only his time apart from the rest of the world, but also — and perhaps more importantly — what came after. In part, Nasubi’s home in Fukushima – which had a power plant that experienced a nuclear meltdown after being hit by an earthquake and tsunami in 2011 – helped spur him into helping others and finding his way.

After months of being subjected to cruel manipulation by “Denpa Shonen” producer Toshio Tsuchiya (who is also featured as an interviewee in “The Contestant”), Nasubi was left mentally and emotionally debilitated. And while Titley wanted to embolden Nasubi to share his story, she knew it would take steadily cultivated trust for him to say yes to her vision. “There were so many questions that I felt were kind of obvious or natural that people just hadn’t asked him. But consent was an enormous part of the process,” she said.

“I don’t want to say it’s like therapy, but it was like somebody who’d never really opened all those boxes before,” Titley added. “And then suddenly he could.”

Check out the full interview with Titley, in which she discusses building a bond with Nasubi, managing the presence of a Western perspective in the documentary, and encouraging viewers to reflect on their own relationship with the media they consume.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Obviously, this is revisiting an era from the late ’90s and the early aughts, as this sort of nascent moment in reality television, so to speak. How did the conversations to turn Nasubi’s ordeal into a documentary start and how familiar were you with his story beforehand?

I came across his story by accident. I was researching something else. You know when you get distracted and you start working on something you shouldn’t be? It went down one of those rabbit holes. And I wanted to tell the story about Nasubi. The stuff that I found online had been very, I found quite almost on the verge of being a bit derogatory about kind of either Japanese culture or about him in some ways as well and his ordeal. And a bit perfunctory in the way that’s gone: “Oh, and then that was the end of it. And he didn’t even become an A-list celebrity.” That was kind of the end of the story. And I really wanted to do something about him.

So I approached him and said, “I want to make a film and I want to make it about you and your story.” And we kind of had this open dialogue that kind of went back and forth. And we talked about the things that were important to us about making the film. You know, one of the things that was really important to him is he really felt that Fukushima was a very important part of his life. And he really wanted Fukushima to play a role. And I was in total agreement. So Fukushima was always going to be a big part of the film in some way, have a role.

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)In prior depictions of his story, I’m assuming Fukushima was not really a part of it at all, because most of what it was sort of focused on, which you touch on in the documentary, was this sort of ascension into the ranks of entertainer, as a comedian. The focus was much more on his career prospects, so to speak, rather than how it affected him mentally and emotionally.

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)In prior depictions of his story, I’m assuming Fukushima was not really a part of it at all, because most of what it was sort of focused on, which you touch on in the documentary, was this sort of ascension into the ranks of entertainer, as a comedian. The focus was much more on his career prospects, so to speak, rather than how it affected him mentally and emotionally.

But it was also quite a car crash TV as well. I think that’s the thing. I think also, say for maybe the “This American Life” podcast, and a lot of the YouTube-type things that have been done and print, or online kind of reviews of it had been sort of like, “Look at those crazy Japanese — isn’t this a crazy story?” And then that was kind of the end of it, and not really dug any deeper, particularly about his story.

So I really wanted this to be a film about Nasubi and about his journey. Of course, it is a film about reality TV as well. But that wasn’t the intention. The intention wasn’t to be kind of like, “Here’s the beginning of reality TV. This is a potted history.” That was never the intention. It was very much about his experience of that kind of period in history.

“The Contestant” uses Nasubi’s testimony to delve deeply into his story and the mental and emotional toll that “A Life in Prizes” had on him. I’m wondering, how were you able to get him to come on board for the project without making him feel as though he may be exploited all over again?

No, completely. What’s interesting, actually, kind of relates back to the other question as well. When we did start talking to him, it felt a little bit like, “Oh, I’m pretty certain actually, that it was the first time that he’d really got to unpack his story.”

There were so many questions that I felt were obvious or natural that people just hadn’t asked him. But consent was an enormous part of the process. I made sure that all the way through we talked about it. I double-checked with him that everything was OK. He was involved. He never had editorial control and he was aware of that. And that was something that’s important. But he was involved in the process. It was it felt like a collaboration, and we made sure we didn’t do anything that he wasn’t uncomfortable with.

And it was baby steps in a weird way. It took a very long time. And that’s frustrating in so many ways to make this film. But in other ways, it maybe helped the film a lot and served it quite well. Because the film’s finished now, and we’re good friends — we’ve built this kind of relationship over time. There’s that level of trust. I’m fairly certain that because of what Nasubi’s been through — when he first came over to the U.K. and we met for the first time, and shot a tester tape — I think he was still worried that he was going to get to the airport, and there was going to be nobody to pick him up or that it was all going to be a big prank.

I think he mentioned something along those lines, that there’s still that part of him that’s ever so slightly worried that it’s a bit of a game show. But no, I think there’s a level of trust there now.

I don’t know if you’ve seen “Jury Duty”?

No, but I’ve heard about it, yeah.

The guy who was the subject of that show expressed a similar sentiment once all was said and done. Because if you know the premise of the show, everyone who was in it was part of the show. And when he learned that, they went through this whole, phony jury trial, he was really, not only disoriented, but I think there are reports out there that said he spent a significant portion of time in the weeks and months that followed being paranoid in effect that he was being videotaped or just recorded or just who was he interacting with? Was it an actor? Was it a real person? So that’s really interesting to hear.

That’s exactly what happened to Nasubi as well. And we don’t put enough of that in the footage — I mean, we’re constrained by everything else. But that’s exactly what happened to him, that he would be paranoid that people were filming him, he just struggled to communicate with people on that kind of level, because he wasn’t sure. And everything, everything he did from then on, he was just sort of paranoid about. So I think he did retreat back to Fukushima in a way.

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)I remember that part of the documentary where he says, you know, I even had trouble making eye contact with people the same way. And just his communication skills, he felt had just regressed so significantly, which was heartbreaking. You were talking about that trust you kind of cultivated with him. Was there anything specific that you did on set to maintain that level of trust?

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)I remember that part of the documentary where he says, you know, I even had trouble making eye contact with people the same way. And just his communication skills, he felt had just regressed so significantly, which was heartbreaking. You were talking about that trust you kind of cultivated with him. Was there anything specific that you did on set to maintain that level of trust?

So, the way in which we filmed it was actually remote, because it was in the middle of COVID. I think it was just that communication. So I think the ongoing thing was that we would ask him, we would ask him sort of even visual ideas, you know? We were kind of going, “We’re doing the diaries, and we’re not sure how to illustrate them in this way. Have you got any suggestions?” Or, “We’re looking for a voiceover artist to do this. Have you got any suggestions of somebody who you think might be good?” So I suppose we asked as a creative input in that kind of a way.

He’d come over to the U.K. for a couple of weeks when I’d been pitching the idea for some time, and it was the usual sort of story where you can’t quite get the funds and I needed to do a test of tape, I felt. And he said, “Let’s make this film.” Once he’s committed to something, as you probably know, he’s quite committed, which is handy for me. So he came over to the U.K. and we had this sort of two-week holiday where we spent some time down on the Isle of Wight as well. The interpreter lived around the corner. And we just had all this time to hang out. We’re playing table tennis in the evenings and long car journeys and ferry journeys and walks along the beach and hanging out with my family and the interpreter’s family and a couple of other Japanese people we knew nearby who were intrigued to come along and help. And so it was this slightly random, chaotic kind of holiday that we had. But I think that broke down all those barriers.

I think, usually you would assume that in creating a documentary like this that is sort of probing someone’s past trauma, there would be, at certain points, some hesitance or maybe they want to back out. But with him, it’s interesting that, as you just said, because of his personality — and even the way he approached the challenge — he was really all in.

I think this is also the first time that he’d had this opportunity to tell his story. And he knew when he trusted us and he knew that this was an opportunity to tell his story, he felt, “Right, this is it. I’m not holding back.” And we did two days of interviews with him. And I remember we were getting halfway through the second day, and he was saying, “We’re going to have to book in another three days because I’ve got so much to say!”

And we were like, “Well, I’m not sure we can do that.” [Laughs] But he had so much more to share. I don’t want to say it’s like therapy, but it was like somebody who’d never really opened all those boxes before. And then suddenly he could, and we gave him the space to just really unravel all those thoughts.

That’s a good segue into my next question, because the other really prominent component or participant of “The Contestant” is Toshio Tsuchiya, who’s obviously the producer of “Denpa Shonen” and was the mastermind, so to speak, behind “A Life in Prizes.” And it’s interesting because I think the way that he at least speaks in the documentary is very open. Was he readily willing to participate in the documentary?

Yeah, he was. We approached him via Nasubi. It was actually Nasubi who asked him. I can’t speak for Tsuchiya, so this is totally my opinion, but I feel that he was taking part in the documentary for Nasubi. I mean, he’s made it clear that’s what he was doing: he was taking part for him, not for me. This is no favor to me that he was doing.

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)I think one of his final quotes in “The Contestant” is, “I would consider laying my life on the line for this person,” which was very profound. Were you surprised by how unabashed and honest he was and how he spoke throughout? Not only about Nasubi, but also the extent to which he was extremely open about his feelings and motivations in producing the show?

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)I think one of his final quotes in “The Contestant” is, “I would consider laying my life on the line for this person,” which was very profound. Were you surprised by how unabashed and honest he was and how he spoke throughout? Not only about Nasubi, but also the extent to which he was extremely open about his feelings and motivations in producing the show?

I’d done preliminary interviews with him, very basic ones, so I knew all of those things. I think I wasn’t extremely surprised that he was so open, but I was very grateful that he was, because I just knew that at any point he could sort of say, “I’m not answering that. I’m not going there.”

But he didn’t. And I am really grateful to him because he didn’t hold back. And we didn’t hold back on what we asked him. He’s a TV producer, he’s a documentary filmmaker himself, as well as reality TV. He’s not silly — he knows what we’re going to ask him. He knows the worst that we could ask him. So he wasn’t going in naive by any means. And so I’m quite grateful to him for his sort of bravery and courage and his openness in all of that. He also knows how Western media is going to portray him or how he will be seen in Western media. So he was aware of that as well. And he still did it, and he didn’t do it in a cagey way — as you said, he was open and forthcoming.

Do you think “The Contestant” would have been a different documentary if Tsuchiya had not participated? And what do you think it would be missing?

When we were developing it, there was always that chance that we might not get him involved. I think it would have been a good film, but it maybe wouldn’t have been a great film. It would have been different. And I just think it’s so interesting, you know, his side of things and his reasonings . . . it would have been possible. It just wouldn’t have been the same film, I think.

Japan has been described as a country that embodies collectivist tendencies. How much do you feel that those tendencies may have played into the way Nasubi’s plight was handled by the viewership or the audience, and by Tsuchiya and the crew of “Denpa Shonen”?

Oh, that’s a really in-depth question. I suppose there are so many different levels of that. With the crew, I don’t know, there’s that level of superiority and that kind of work mentality of doing what your boss tells you to and so forth. But I only spoke to Kagawa and Tsuchiya. I don’t think we managed to speak to, off the top of my head, many other crew members.

I guess I’m thinking specifically about how, Tsuchiya in the documentary often talks about his obsession with capturing something incredible as almost justification for why he subjected Nasubi to everything that he did, which from my interpretation was something incredible to show Japanese viewership and audience or to the world. And I wonder if you feel that that was the case — that there was an underlying motivation to produce something for the masses on behalf of the masses and this sort of collectivist mentality.

I don’t know whether he was doing it for the sake of the masses and everything. I don’t know. I know that he very much believed in capturing this essence of truth. I think he thinks of himself as an artist in that way, that he’s capturing this level of truth in that way. Whether he feels that he must show that to the masses, for this collective responsibility, I’m not sure about that. I was interpreting it more in terms of the audience, about the kind of the collective, what’s the word? Complicity. Do you know what I mean? I’m also being really cautious that I’m a white Western woman commenting on Japanese culture.

You worked alongside Japanese producer, Megumi Inman, for “The Contestant.” As a U.K. filmmaker, how else did you mitigate the presence of a Western voice in making a documentary that is based in Japan and focuses on Japanese people?

I just listened. I tried really hard to listen and listen where I could, whether it happened to be with Megumi or whether it happened to be with other people that I —not just professional Japanese people or people involved — but people I met who might have known his story. People who were in Japan in the late ’90s, and early ’90s. I quizzed them all the time from the moment that we started making this all the way along and about interpretations. So I grew up abroad in South Asia, and I’m aware of how easy it is to stereotype other cultures in that way. I’ve been the outsider and I’ve seen it from the other ways of people kind of stereotyping cultures that maybe I know from a slightly different perspective, and so I was cautious of that.

So yeah, I think just by listening and making sure that I fed back. And I’m sure I haven’t got it 100% right, and it’s quite hard because the desire from, Western storytellers is quite high to make sure that you see things in black and white, good and evil. Whereas Japanese narratives just aren’t that way, and that’s not how they see the world.

The other person that I spoke a lot about it with was Juliet Hindell, and we’re both on the same wavelength — she’s a British journalist who lives in the U.S. now, but was out there, very much embedded in the story. I was really nervous about using her, and I told her as much, about involving her in the story because I really didn’t want to have a Western narrator at any point. It’s hard because, you know that the outside influences are, “Well, if you do this, then it would just wrap all this up quite nice and neatly and tell everybody what to think.” But I didn’t want to tell everybody what to think. I wanted their voices to come through, and I worried with Juliet in there that she might be seen as a commentator. So the fact that she’s embedded in the film and she’s very much an important part of the story made it all right, made it OK really for her to have that role. And also we could have her context and know that it wasn’t colored as a kind of a Western historian might kind of come out with this perspective.

Even though we’re not watching Nasubi live as viewers were in the late ’90s, I feel like “The Contestant” really begets such a strong sense of complicit voyeurism, as you were saying before. How much, if at all, did you want viewers to feel a sense of complicity in this story, which you kind of touched on already?

“I wanted people to feel uncomfortable.”

One of the things that we did was we, the archive that we had, we didn’t have the dailies, the rushes; we just had what went out on air covered in all that graphics and all the audio. It’s an onslaught, and one of the things that we wanted to do was strip it all back, which we did with visual effects, so that could see him naked in the room. But the other thing was that we wanted to recreate it in English, so you got a real sense of what it was like as a Japanese person watching it.

But it was really difficult putting the laughter track back on, and it was really hard to do, actually. There were certain places where like, “Oh, do we have to have it here?” Because it just felt cruel and mean. But at the same time, I wanted people to feel uncomfortable, I wanted people to laugh.

I’m curious if the reality landscape of Japanese TV has changed since then. Were the ethical issues from “A Life in Prizes” ever addressed for this? Are there contracts and more transparency these days in that industry? Notably, Nassabi never signed a contract, which his manager, I believe, said was not because he was gullible, but because he was naive.

Yeah, there’s two things. One’s kind of like, looking back at it, Japan is not as litigious as the U.K., or particularly the U.S. back then or even now. And also we’re kind of looking back at it with 20 years of history of reality TV. If you or I said yes to a reality TV show, we know that we’re going to be manipulated, whereas nobody back then had any idea. It’s totally understandable that somebody would walk into a show and just not expect that.

But, and I’m not really the person to kind of comment on this —the state of reality TV anywhere, really, let alone Japan — but it was interesting when we met Tsuchiya for the first time. We met him in London at a Comic-Con, and we were chatting away, and we said, “People are going to be really critical of you. Are you prepared? Because people think that ‘Denpa Shonen’ and ‘Life In Prizes’ was incredibly cruel.” And he pointed out, “Well, maybe. But actually, we would never do anything as cruel as ‘Love Island.'” I mean, he had a point — there were two suicides at the time, you know, linked to “Love Island.” And so I thought that was just an interesting take.

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)It is interesting to think about, how even when you watch something like “The Kardashians,” and there’s a really juicy segment, you have to think that, “OK, there was probably something done to maybe provoke that scenario or, or create a situation that would be interesting for viewers to watch.”

Tomoaki “Nasubi” Hamatsu in “The Contestant” (Disney)It is interesting to think about, how even when you watch something like “The Kardashians,” and there’s a really juicy segment, you have to think that, “OK, there was probably something done to maybe provoke that scenario or, or create a situation that would be interesting for viewers to watch.”

But in Nasubi’s case, you can tell had no sense of understanding about what he was really getting into. And I think that really culminated with the look on his face when those walls of the fake waiting room were removed. He’s absolutely stunned. And for me, that was the most heartbreaking scene in the show, in the documentary, because of just how confused and shocked he was, he just had no understanding of what was going on.

He says, “My house fell down,” doesn’t he?

That was the line that got me.

Yeah. It’s so, so tragic. That gets me every time. And then weirdly, the party poppers in his face — I can’t watch that. I just find that really hard, actually.

The ethical issues I think raised by “The Contestant” feel especially relevant today, as we’re saying in reality television and social media documentaries and more. We obviously live in a world where we’re able to share personal experiences and information about our lives very easily, as well as, obtain that information about other people if we want to. Do you see “A Life in Prizes” as having portended that? It came very shortly before things as big as “The Truman Show” and “Big Brother,” for example.

It feels like it did. I don’t think it did it, you know, intentionally, obviously, but it is interesting. It’s interesting — we didn’t go into it in the film, but, you know, the idea of product placement as well. I don’t think it was even something they were thinking of, but all of these kinds of things — it’s like he’s an early-day influencer, but without him actually knowing that he is. That’s the weird thing about it all. And it is weird to think that, now we choose to do all those things that he was doing, whereas back then, A) he had no idea and B) I think it’s easy to forget that it was really difficult to be famous back then. The whole idea of your 15 minutes of fame — you had to do something pretty insane. To get to be on TV was a big deal, whereas now, if you were to post something up — well, maybe not me, but — post something up and you could make that happen.

What do you want viewers to glean from “The Contestant,” insofar as it relates to digital and media ethics in contemporary times, if anything at all?

I think I’d like people to reflect on their own relationship with it, whether that’s with reality TV or whether that’s with social media, and to think about their own relationship with it. For the first time, I think in a while, it feels like you could just be a couple of years age difference from somebody and your whole experience of media, social media, all of these things are so wildly different because technology has moved so, so fast. It’s so different. It used to be that if we were in this decade together, we had similar kinds of experiences or the same things. But now you could just be a couple of years older than somebody or whatever, and your whole different perspective — because you were a certain age when Facebook came out or a certain age when Instagram or whatever it is — it’s so different. And I find that’s quite interesting. Reflecting on your own, on people’s own relationship, whatever that might be.

“The Contestant” is streaming now on Hulu.

Read more

about this topic