Every detail would be thought out, and run with the exactitude of an operatic performance. The aim, the goal of all art – transcendence.

He brought in top chefs from Hong Kong and waiters from Italy, who dressed in designer suits and were schooled in placing plates on starched white tablecloths in a precise, three-fingered grip. There were no chopsticks in sight.

Chefs performed for guests, hand-pulling Beijing noodles in the dining room. Servings were small, and prices intentionally colossal. Instead of dinner, what was served was luxury and dreams.

He called his restaurant Mr Chow, a calculated name. And with it, he, too, became Mr Chow – the only way he “could get people to call me ‘mister’”.

“I’ve faced prejudice all my life,” says Chow, now 85, on a video call from the US city of Los Angeles, where he lives with his fourth wife and two young children.

“All Asian men in the West, apart from those who’ve become what they call a ‘banana’ – yellow outside, but white inside – are always afraid. I’m less afraid now, but I wasn’t back then.”

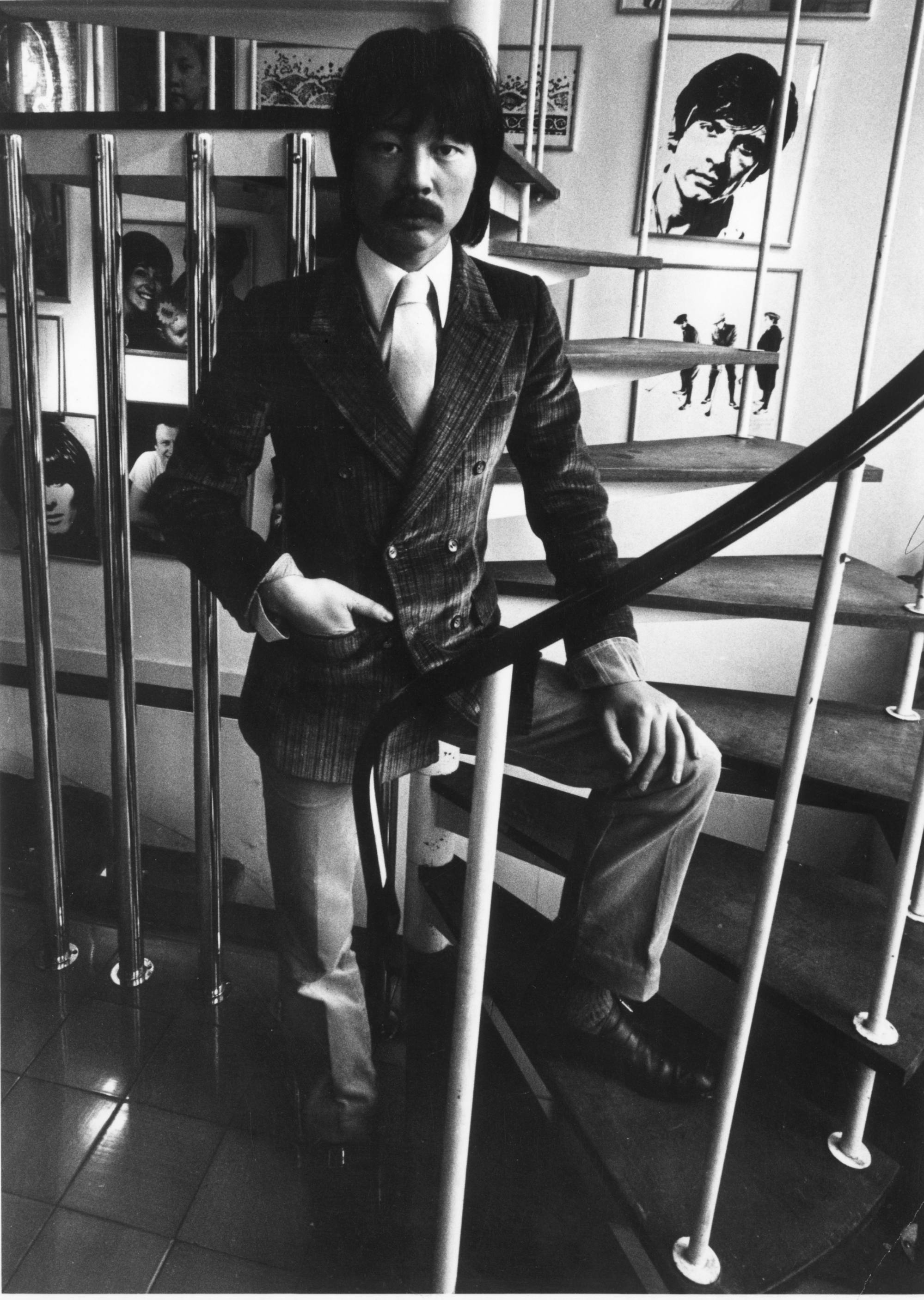

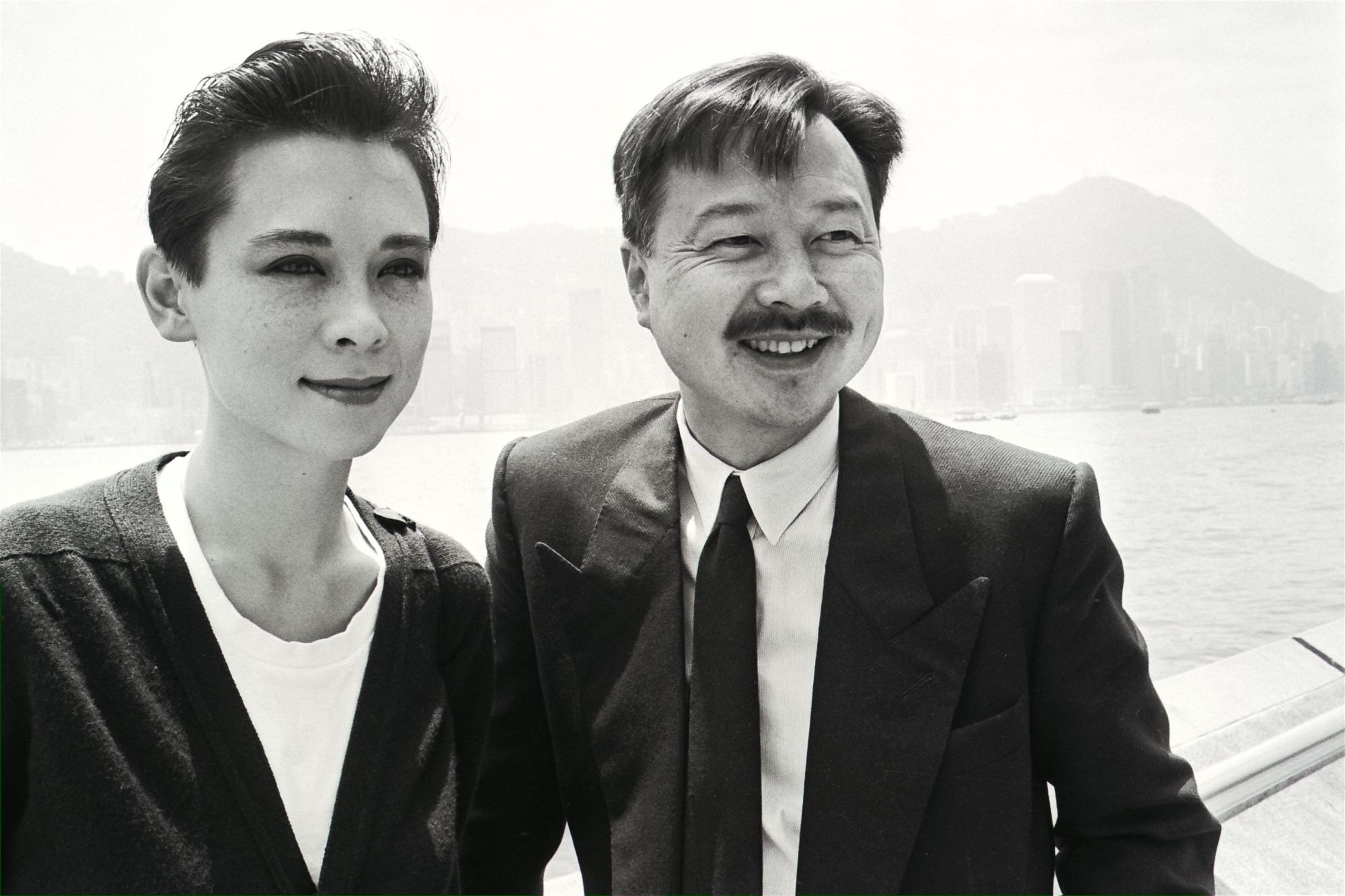

Along with creating a restaurant that imitated theatre, he created a character to play within it – the persona of Mr Chow, with his trademark bottlebrush moustache and, later, his boldly rimmed round glasses.

In class-conscious British society, where only three characteristics – being “eccentric, artistic, or princely” – could possibly eclipse foreignness, Chow exaggerated his considered idiosyncrasies.

“I deliberately developed a life in the limelight so the racism would be more bearable,” he says. “If I’m famous they’ll be nicer to me, or I’ll be back in the queue again.”

He also opened branches in New York’s Tribeca (2006), Miami (2009), Las Vegas (2016) and Riyadh, in Saudi Arabia, which launched in October last year.

Although, over the decades, branches have opened in other cities, only to close, and the restaurants were sometimes panned by food critics (a New York Times review in 2006 gave Mr Chow Tribeca zero stars), the brand remains iconic because of its lauded history and glittering clientele. Another outpost is expected to open this year in Dubai.

In 2018, a book commemorating five decades of the original Knightsbridge Mr Chow was published: Mr Chow: 50 Years features a painting by Keith Haring on the cover, depicting Chow as a green prawn – the Mr Chow dish of green prawns was said to be the American artist’s favourite.

Other artists have captured Chow in portraits, including Blake, who painted Chow’s likeness in bright yellow, and Hockney in ink.

Last year saw the release of the feature-length HBO documentary AKA Mr Chow, which attempts to get beneath the persona to the person within.

“It’s all the same thing,” says Chow, “there’s only one me and I’m trying to be truthful. I hope that comes across.”

He is now married to Vanessa Rano, nearly 50 years his junior, with whom he has two of his five children.

While he says he remains at the helm of his expanding restaurant empire, Chow is today as much an artist as a restaurateur, having picked up his paintbrush – and hammer, blowtorch or can of spray paint he uses in his large-scale abstract works – in a return to his youth. In those days, Chow turned to art in loneliness.

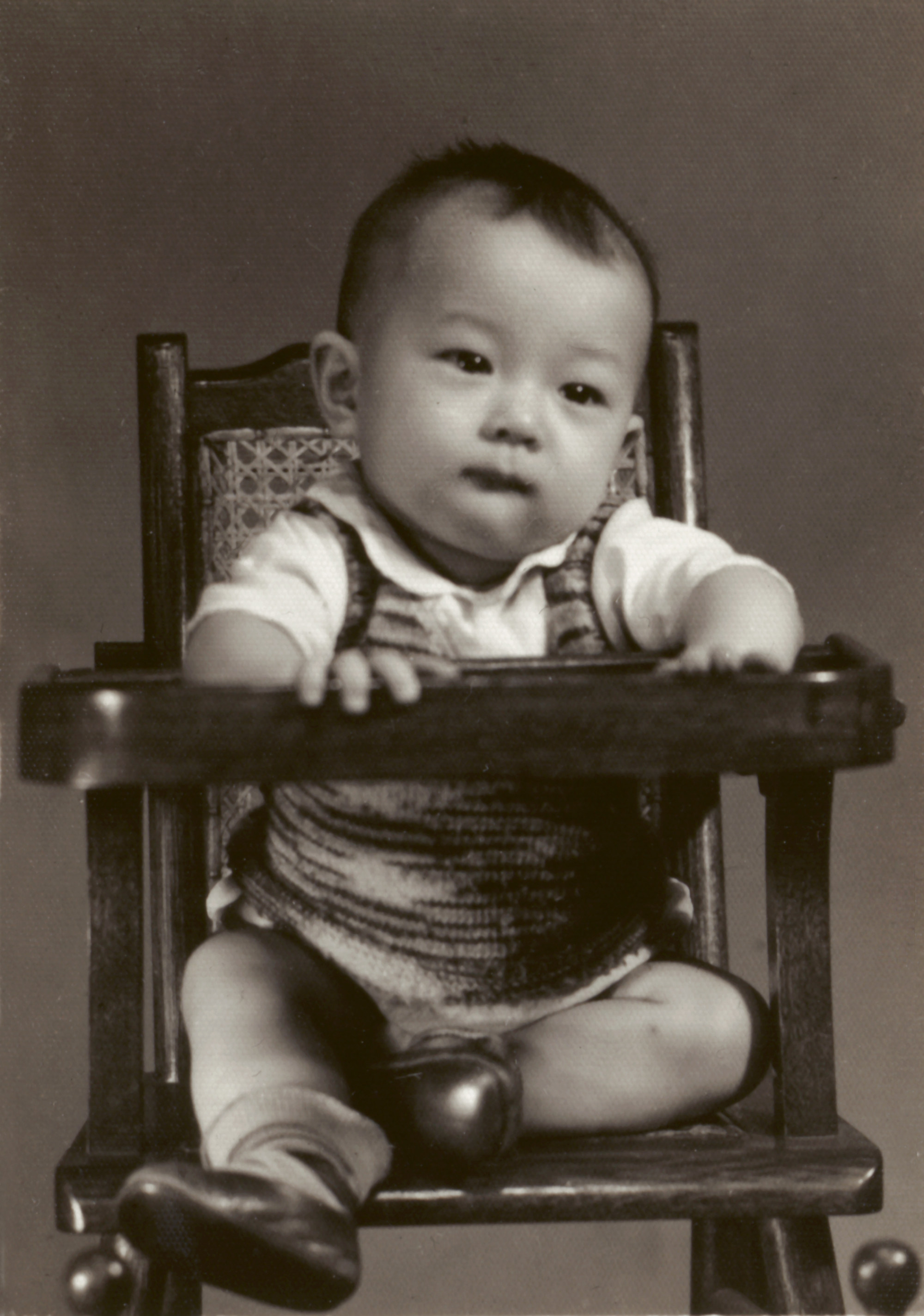

Chow was born in Shanghai in 1939 as Zhou Yinghua, son of the national treasure Zhou Xinfang, who founded the Qi performance style, and of his quarter-Scottish mother, Lilian Qiu, whose family had made their fortune in tea.

He left behind his pampered life of chauffeurs and servants aged 13, with the political situation in China continuing to deteriorate. He and his sister Tsai Chin went via Hong Kong by ship to Britain.

Before he left, Chow spent a magical two weeks with his father, who was usually too caught up in his theatrical life to spend much time with his children.

His father’s parting words have echoed ever since: “Wherever you go, always remember you are Chinese.”

Chow’s mother was beaten to death by zealous members of the new regime.

On the 30-day journey from Hong Kong to Southampton, young Yinghua, who could speak only Mandarin, became Michael Chow, his English name given by his Catholic mother.

He and Tsai Chin arrived in the British capital in late 1952 during the Great Smog of London, a toxic cloud of pollution that enveloped the city, leaving the streets in near darkness and killing up to 12,000.

Art was his only solace.

“Art is an antidote to suffering,” he says. “Take away art and you may as well commit suicide.”

Chow would then enrol at London’s lauded Saint Martin’s School of Art, followed by the Hammersmith College of Art and Building. He tried to make it as an artist, both before and after opening Mr Chow, but was largely dismissed.

“All my life, by force as it were, due to political reasons, they haven’t wanted me to be an artist,” he says. “As a boy I was p****d on all day long, as a younger man I was condemned because I’m Chinese to only do a restaurant or laundry.

“When my restaurant was a hit – my Chinese restaurant, which is, of course, the worst of the worst – then a restaurateur wasn’t allowed to paint. I said I was a Renaissance man and they hated that.

“But great art needs suffering, and I have suffered, even if on the surface I haven’t shown it. I have no complaints, I’m happy where I am now. I’m old but I’m just beginning.”

In 2022, London’s Waddington Custot gallery hosted Chow’s first solo exhibition in Britain in nearly 60 years.

Chow was a keynote speaker at a private lunch hosted by East West Bank before the fair, and a short film about Chow created by French immersive installation company Nova Pista was screened by Sotheby’s at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre after the fair.

Next year will mark 130 years since his father’s birth, and the 50th anniversary of his death, and Chow will take part in a range of exhibitions and celebrations in mainland China to honour him.

The decades may have passed but Chow’s art, which he signs these days merely with the letter “M”, remains deeply informed by his father and his parting words.

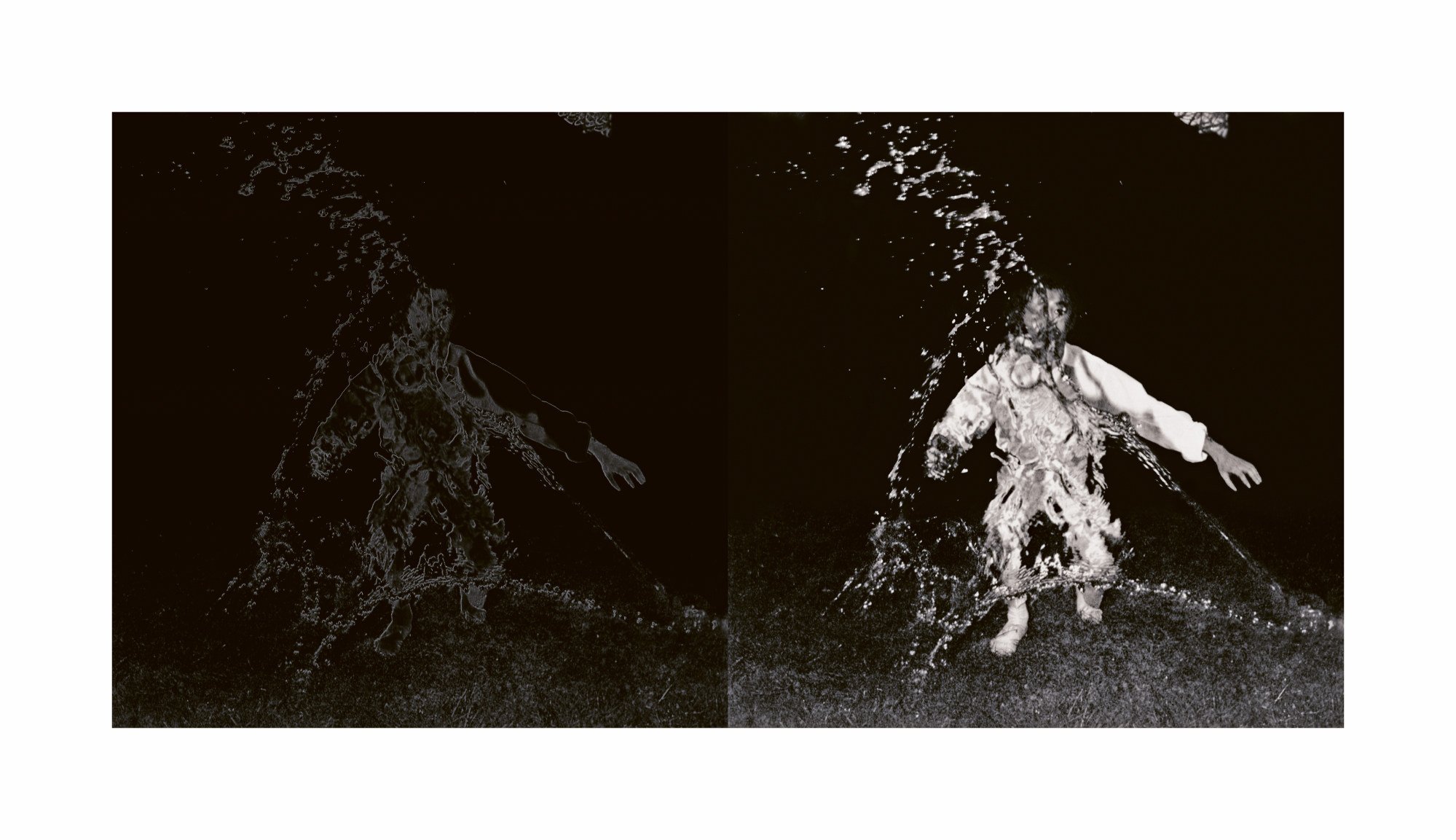

While his artworks – usually large canvases covered in a highly performative process with layers of dried paint sculpted into three-dimensional forms with collage techniques – may look nothing like calligraphy, Chow borrows the physical approach from Chinese writing.

“The action of one stroke, a constant mastery of technique so that when you have a canvas in front of you,” says Chow, “you do a single expression and that creates the work – that’s very much part of my practice.”

In his “One Breath” paintings, the approach is crystallised. He applies one or more large dabs of paint, or objects such as eggs, to paper, and in one fast movement slams it with a chunky hammer.

“‘One breath’ – it’s a martial art technique, it’s so quick it’s internal, you don’t even have to think, it’s emotion. In that moment magic happens, it’s poetry. All Chinese art has it, and so does Chinese cooking,” says Chow in a short film recorded for his Sotheby’s show in Dubai 2022.

In his early days, he opened a hair salon with his business partner, Robin Sutherland, which they sold to British supermodel Twiggy. He has also worked as an interior designer, having created the Giorgio Armani boutiques in Beverly Hills and Las Vegas.

Rather than being a maestro of reinvention, Chow sees his many roles as being part of a unified body of work – as opera masks worn by the same master.

“Life is all about recipes. Oppenheimer’s atom bomb is a recipe, an abstract expressionist work or a landscape painting is a recipe,” he says. “Take a Francis Bacon, you turn the canvas around, you use this kind of primer, this kind of paint, then you put a little salt, then a little of that, and you get a Francis Bacon.

After a moment, he continues: “But don’t misunderstand me, I don’t subscribe to that cultural superficial bulls*** of being so humble. Please, don’t be a hypocrite! I want to be one of the greatest living artists, and why shouldn’t I say that?”