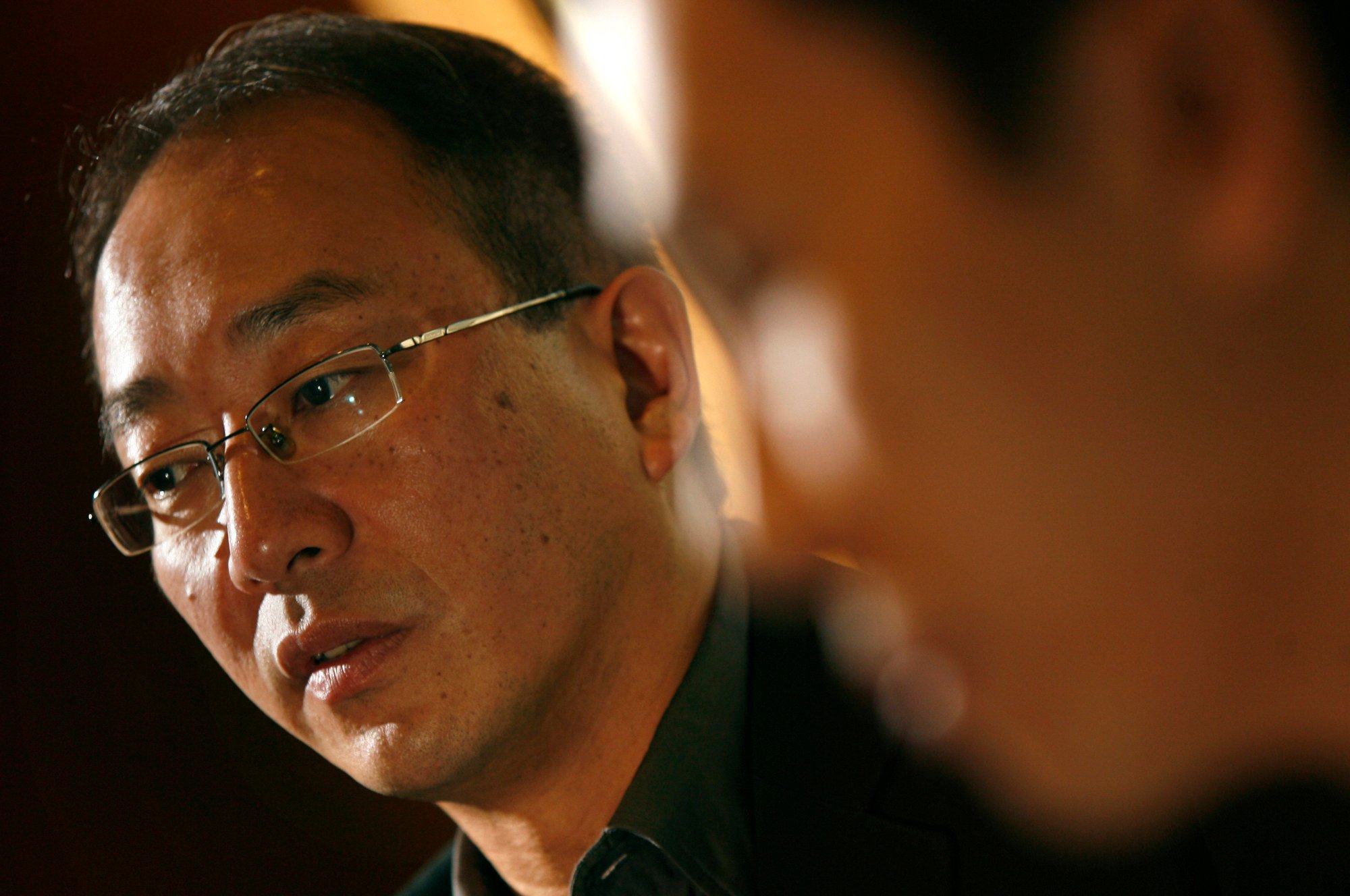

So credit must be given to Hong Kong director Daniel Lee Yan-kong for trying something different in this 2008 adaptation of one of the stories from the novel.

“Zhao Zilong remains undefeated until the Fengming Shan battle, late in his life,” Lee told the Post in 2008. “When he is trapped in battle, he looks back on his life and his achievements. His life is a good reflection of the wisdom of the book: what goes up must come down.”

The story is set in the Three Kingdoms era (220AD to 280AD), a bloody period of Chinese history when three states, the Wei, Shu-Han, and Wu, were waging war. The story starts when Zhao (Lau) and Luo (Hung) become friends and join the Shu army.

Zhao rises up the ranks to become a great general, while a jealous Luo watches from the sidelines. The finale finds Zhao placed in a difficult military position by his emperor, and betrayed by his old friend out of spite.

Much of this is down to a superior performance by a grizzled Lau, who brings sensitivity and gravitas to the role of the much maligned hero.

“It’s such a well-known story, I was very nervous,” Lau said in an interview at the time. “There are three perspectives on Zhao: historians’ professional knowledge, how normal people like us remember him, and his character in a popular computer game. I can’t satisfy all these, so I just tried to stay true to the script.”

Lee said he had been familiar with the story since childhood, when his father would tell him stories from Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

According to a Post report, Lee had written a work of literary analysis about the novel. “If I could only make one movie in my life, Three Kingdoms would be the one I would aspire to make,” the director said.

The film’s action and martial arts scenes were choreographed by Hung, Hong Kong veteran Yuen Tak, and a massive team of helpers. The battles are modern in style, with fast cuts and multiple camera shots, but Hung ensures the individual martial arts moves can always be seen. Special effects are involved in the action, but they do not dominate.

The actress proved to be much more than a decorative “vase”. She was highly effective in her warrior role, which was surprisingly nuanced; although violent, Cao always insists on a fair fight.

“I came to this project as an outsider, not really understanding the history of it, not speaking the language and not having any background,” Q said in an interview. “So I just had to shut ‘Maggie’ off for a while and really believe I was this person. It was probably the most difficult film I’ve done yet.”

God of War (2017)

His fascination for battle scenes started young – he once told this journalist he used to enjoy staging battles with tiny Airfix-brand soldiers when he was a boy.

Chan, who was one of the most versatile directors of the 1990s, had made some average period fantasy pieces, such as the The Four film series in the 2000s. But he did not get the chance to make a grandiose war epic until 2017’s God of War.

The massive Hong Kong-China co-production is based on the well-worn tale of a Chinese general defending the Zhejiang coastline from Japanese pirates in the 16th century.

“After more than a decade in the creative long grass, Hong Kong director Gordon Chan bounces back with God of War, one of the strongest films of his career,” Derek Elley – an expert in Asian films who is also an authority on Hollywood epics – wrote on sino-cinema.com.

“Grittily realistic and well dialogued, rather than fantastic and VFX-driven, God [of War] shows that Chan still has some juice left,” Elley added.

The battle scenes, choreographed by Qin Pengfei and a more experienced action director, Kenji Tanigaki, are masterfully executed. But long historical interludes slow the film down.

God of War benefits from the presence of Vincent Zhao Wenzhuo in the starring role of Qi Jiguang, the general who turns the Ming army into a formidable fighting force.

But Zhao’s film career did not take off back then, and went on to make it big in television martial arts series.

Here, at age 45, Zhao stepped into the limelight once more, showing he could still use a sword well, and his fists even better.

Zhao’s old-school kung fu pole fight with Sammo Hung, in a supporting role as a failed general in the early part of the film, is one of the movie’s highlights. But the tour de force is his lengthy final bout with veteran Japanese-born actor Yasuaki Kurata. They start off using swords, then switch to daggers, and fists.

Like most of the epic war films produced in mainland China, the film has a nationalistic message, pushing the theme of the Chinese people’s unity in the face of adversity.

Even so, God of War is unusual in the way that it features some traitorous Chinese among the pirates, as well as making Kurata’s Japanese pirate chief – a military general posing as a buccaneer – a man of honour.

In this regular feature series on the best of Hong Kong cinema, we examine the legacy of classic films, re-evaluate the careers of its greatest stars, and revisit some of the lesser-known aspects of the beloved industry.