In Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, the local fudge shop is called Cottage of Sweets. In Stratford, Ontario, it’s Nudge Nudge Fudge. Sarasota, Florida; Juneau, Alaska; and Provincetown, Massachusetts, all have a Fudge Factory. In Mystic, Connecticut, there is Mystic Fudge, and in Cape May, New Jersey, you will find the Original Fudge Kitchen. Niagara-on-the-Lake in Ontario has Maple Leaf Fudge.

These towns are, like all places, unique—full of particular politics and personalities—but they also have much in common. They are the kinds of places that contain multiple stores that stock regionally specific seashells and a rotating display of nameplate keychains featuring a local food or animal: a lobster, say, or an orange. In any of these places, you can almost certainly buy a waffle cone scooped high with butter pecan ice cream, and you can surely eat a hamburger with special sauce and drink a local beer as you look out over a pleasing vista, most likely a body of water with a harbor full of boats. And, of course, weirdly, in each of these places, you can eat fudge.

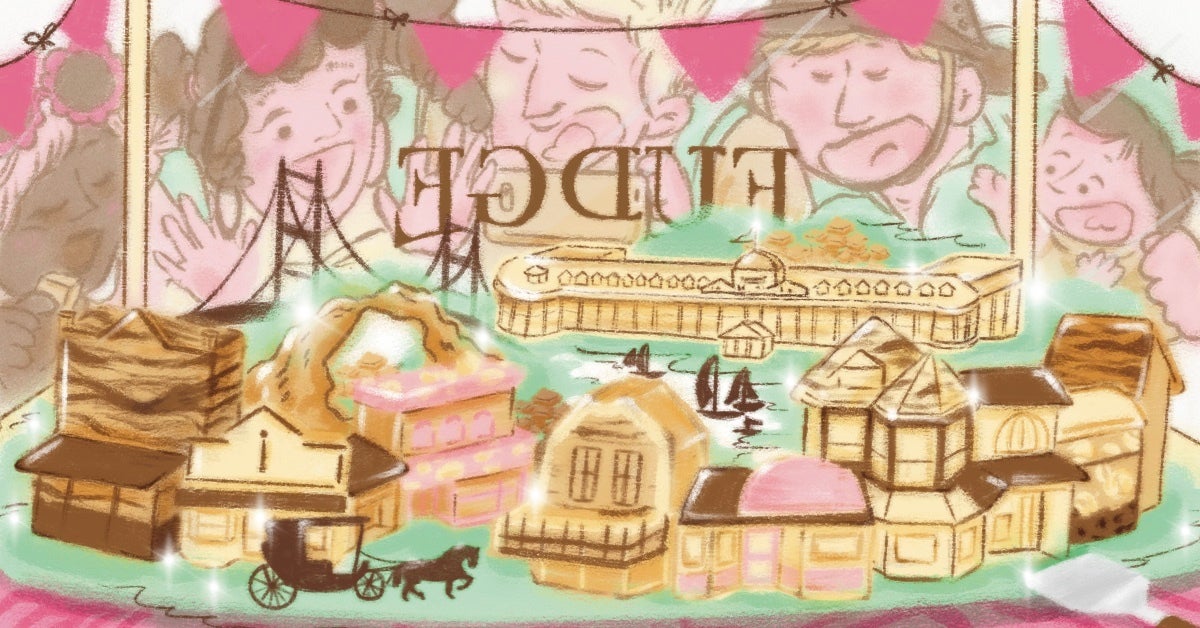

The country’s first town to marry fudge and tourism—the one that kicked off North America’s love affair with the sugary, chocolaty treat—is scarcely different. On Mackinac Island, which is four square miles and sits between the Upper and Lower peninsulas of Michigan, just under the Mackinac Bridge, one can buy ice cream at Joann’s and go to Little Luxuries to pick up a few Petoskey stones: rocks dotted with fossilized coral available exclusively near the Great Lakes. There are no gas stations because, since 1898, cars have been banned on the island. The whole place runs on horses, bicycles, and, during a large portion of the year, snowmobiles. Main Street, which is less than a mile long, has no fewer than 13 fudge shops. The island imports ten tons of a sugar every day.

In Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, the local fudge shop is called Cottage of Sweets. In Stratford, Ontario, it’s Nudge Nudge Fudge. Sarasota, Florida; Juneau, Alaska; and Provincetown, Massachusetts, all have a Fudge Factory.

The story of how fudge came to Mackinac Island and, eventually, the world starts with the story of the island itself: a hub of the fur trade and the site of an important British fort in the 18th century. In the early days of contact with the French and British, the indigenous Odawa people in L’Arbre Croche sold as much as two hundred thousand pounds of maple sugar each year. Much of that sugar was shipped down the Great Lakes, but well into the 19th century, some was sold on the island in birch bark containers called mokuks—the original sweets of Mackinac.

The island is cool, even in the summer, and boasts limestone cliffs and pine forests. By the 1860s, the dramatic topography and the weather of Mackinac Island transformed it from a trade center into a tourist destination. In the years following the Civil War, vacationers began traveling to Mackinac to escape the growing cities and the pollen (at the time, the only remedy for people with hay fever was to spend allergy season away from the offending plants).

When tourists stepped off the ferries onto Mackinac Island in the 1860s and ’70s, they found an abundance of candy shops, which were increasingly common in oases across America catering to those looking to escape the heat of a crowded city. At first, the confectionaries on Mackinac were similar to all the others, offering a wide variety of candies and treats such as chocolate-covered nuts, caramels, and the maple candies made by local indigenous people. But by the turn of the century, Henry Murdick, a boatbuilder from Vermont, began to sell fudge, capitalizing on a new way that Americans were thinking about sweets.

Fudge is a relatively recent invention for such a simple substance. A smooth candy that is made by boiling sugar, milk, and butter and beating them until thick and creamy, it first showed up at candy shops and (somewhat bizarrely) women’s colleges in the 1880s. At Vassar, Smith, and Wellesley, students clandestinely made fudge in their dorm rooms using chafing dishes and spirit lamps. It’s an activity that may sound like a wholesome hobby now, but at the time, it was a rebellion against the strict rules of women’s colleges. Students broke curfew to make and eat fudge together, and they were also flouting nutritional advice of the time, which would have had them eating primarily bland cereals. Administrators feared that they would be too stimulated by the fudge to pursue their studies, or that it might, as Sarah Tyson Rorer, a food writer of the era, suggested, “kill the weak and ruin the middling.”

The story of how fudge came to Mackinac Island and, eventually, the world starts with the story of the island itself

Fudge’s invention coincided with a dramatic change in how sweets were perceived in the United States. Until the late 19th century, confections carried one of two connotations: the luxurious indulgence of an expensive chocolate bonbon, or the lowbrow vulgarity of penny candy. But as sugar and chocolate became cheaper and easier to refine, some candy, like fudge, took on a more middlebrow, domestic, and feminized image. Easy to make at home and rustic in appearance, by the early 20th century fudge had become the candy of church bazaars, children’s birthday parties, and homemade Christmas presents. It was a democratic candy, a middle-class candy, an innocent candy. At the turn of the century, fudge-making parties even became sanctioned at women’s colleges. The candy had become thoroughly wholesome.

From the beginning, Murdick’s Candy Kitchen offered tourists fudge. But in the years just before World War I, Henry Murdick’s son began offering something else: an experience. Rome Murdick and, later, his son Gould turned fudge making into a show. Typically, a candy store would make its product at night, but the Murdicks reaized that if they made their fudge in the store window, during business hours, people would come and watch. They boiled the ingredients—sugar, butter, cream, corn syrup, and flavoring—in large copper pots until they reached 230 degrees Fahrenheit. Then they poured them out onto huge marble slabs and used large handheld paddles to dramatically fold and aerate the molten sweets.

Every time they sold a pound of fudge, the Murdicks rang a bell. The fudge show became a popular attraction, and it was more popular still when Gould Murdick innovated a means to pump the smell of fudge onto the street using enormous fans, which successfully enticed even more customers. By the 1920s, Murdick’s was all fudge, all the time. In 1923, it patented the trademark “Murdick’s Famous Fudge.” People lined up down the block to gaze upon fudge being made, and they bought pounds of it to consume as they sat on the ferry docks or took in the island’s scenery from the jostling carts of a horse-drawn carriage.

The depression and World War II hindered tourism and, with it, the fudge trade on Mackinac Island, but you can’t keep a good fudge down for long, and the island and its signature indulgence came back with a vengeance in the postwar era. During the war, soldiers’ rations had included Hershey’s chocolates, which had cultivated a taste for the sweet, and the postwar economy and new highway system meant regional tourists could make their way to Northern Michigan easily and often. By the 1960s, Murdick’s had competition: local businesses May’s, Selma’s, and Ryba’s borrowed the showy tactics pioneered by Murdick’s to became empires of fudge in their own right, and other candy emporiums followed.

It was official: Mackinac Island had become synonymous with fudge.

The popularity of fudge on Mackinac Island, and its eventual diaspora, raises a question: Why do people get so excited about this relatively simple candy when they go on vacation? In part, the Murdicks discovered the answer a century ago: people like a show. But Abra Berens, a Michigan-based chef (and an old friend of mine) who has written several cookbooks about Midwestern food, points out that tourists aren’t coming for pure entertainment. “People are fascinated by these processes that they don’t usually get to witness or be a part of,” she explains. Berens likens watching fudge making to visiting a cider mill or going to a U-pick farm. Most people aren’t farmers or cider makers, so witnessing and playfully partaking in these forms of work is unusual and delightful, even if doing that work for a living would likely be arduous and poorly paid. Fudge is much the same: it offers old-timey proximity married to the thrill of watching a simple product get made. The tourist gets to have all the fun without any of the difficulty.

Fudge still carries the old connotations of wholesomeness and childhood that it picked up in the 19th century, as well as the allure of a special vacation treat. “Seeing candy being made probably seems very novel now,” Berens says. Unlike donuts, cupcakes, or ice cream, fudge hasn’t experienced a renaissance as an urban luxury product—to my knowledge, there are no shops in Soho that sell vegan lychee fudge logs (yet). Like a whiff of lilac in spring, a bite of fudge is evanescent and particular to a time and place. We don’t buy fudge because it’s our favorite candy but instead because it’s the candy we associate with long summer days and refreshing dips in the lake. In order to really enjoy it, or even purchase it, you need to be in a place like Mackinac Island.

Why do people get so excited about this relatively simple candy when they go on vacation?

It is for these reasons, in addition to the basic laws of capitalism, that fudge spread across the country to other tourist towns. In the 1960s, the Murdicks opened shops in nearby Traverse City and Petoskey, and then, later, in Martha’s Vineyard, where the family now owns four shops. In the 1980s, fudge shops began to pop up all over North America—a rich, chocolaty diaspora that took advantage of the allure of this confection of action and smell, nostalgia and sweetness. Today there is hardly a tourist town in America that doesn’t sell fudge.

But fudge isn’t just a treat; it’s also a marker of identity. In the 1960s, Harry Ryba, owner of Ryba’s Fudge and a notorious showboat, gave away pink pins printed with the words “Ryba’s Mackinac Island Fudgie” with every purchase. Ever since, those who vacation in Mackinac—or really anywhere in Northern Michigan—have been referred to as “fudgies” by the locals. It’s not exactly a compliment. Berens describes it this way: “‘Fudge’ is a funny word, and ‘fudgie’ is a funnier one. It’s soft and squidgy, and it makes you think of beached whales gorging on fudge.”

It’s not uncommon for locals to give a nickname to outsiders who take over their towns in the high season. In parts of Florida, for example, they call tourists “cone lickers” because they are always walking around with ice cream cones. Nicknames like these are a marker between outside and inside, between those who spend the money and those that require it for their livelihoods. It’s a way to subtly remind everyone of another truth: It’s not always easy to live in a fudge town.

“It’s really difficult to be working maximum hard when everyone around you is maximum relaxing,” Berens told me. She grew up and now lives in a fudge town in downstate Michigan, a place where people from Chicago visit for the day or the weekend. They sit by the water, have a big meal, and then head back to the city. “When you are on vacation, it’s easy to see things at a distance. There is an alienness to the people who actually live there.” And when a place becomes associated with one thing—like fudge—a lot else that’s true about it gets lost.

“If you work in any restaurant, you are going to get sick of the food.” So says a woman I will call Nicole, a seasonal worker who has been living and working on Mackinac Island for seven summers. “Ninety-five percent of the people who live and work on Mackinac don’t eat fudge. I can’t remember the last time I ate it,” she says. Nicole requested anonymity because Mackinac, like a lot of tourist towns, is a small, tight-knit community. Her job depends on her friendships and connections, and she didn’t want to be perceived as bad-mouthing the place or the tourists who help everyone pay the bills.

However, most of what Nicole tells me is about how wonderful the island is, particularly the parts that most tourists don’t see. She describes the trillium and the lady’s slippers that bloom in the springtime, before most tourists are there to see them, and the many miles of horse trails that run along bluffs, in hardwood forests, and through groves of cedar maples. “You’ll be on a walk, and all of a sudden you come across an apple tree, and you realize that someone probably planted it a hundred years ago,” Nicole says. Most tourists ride their bikes along the perimeter of the island, which is, as Nicole says, “flat as a pancake.” They never venture into the hilly middle, where they can encounter this profound natural beauty.

The other thing the tourists don’t see is the vast infrastructure that makes the island work. The only motorized vehicles on Mackinac are a fire truck and an ambulance, which means everything from trash collection to Amazon deliveries is done using horses and bicycles. Horse manure from over five hundred horses is picked up alongside hotel trash and mixed together to make compost. Non-compostable trash has to be hauled to a landfill off the island using horsepower and ferry rides. It’s difficult work, made more difficult by the absence of cars, the ferries, and the tourists who seem not to see it.

At the end of most summer days, a long line of tourists can be found waiting at the docks for the last ferry back to the mainland. Although there are many hotels on the island—including the famous Grand Hotel where the 1980 movie Somewhere in Time takes place—most tourists head home at the end of the day, once they’ve bought their cherry fudge and bounced around in the back of a horse-drawn bus. Fudge Island recedes into the background as they approach the parking lot where their cars await, ready to take them back to their comparatively fudgeless lives.

After the sun sets, Nicole often picks a point on the west side of the island to sit and look at the Mackinac Bridge. At night, the bridge looks patriotic—the two enormous white towers rise out of the lake, and red and blue lights illuminate the suspension cables. Nicole tells me she watches the bridge sway and shift in the wind and follows the cars as they make the five-mile journey across. “It just kind of twinkles,” she says. “I could look at the bridge every day for the rest of my life.” The 13 fudge shops on Main Street seem very far away.