The women were particularly good at making one beloved Japanese comfort food: the pan-fried dumplings filled with minced pork and cabbage known as yaki-gyoza.

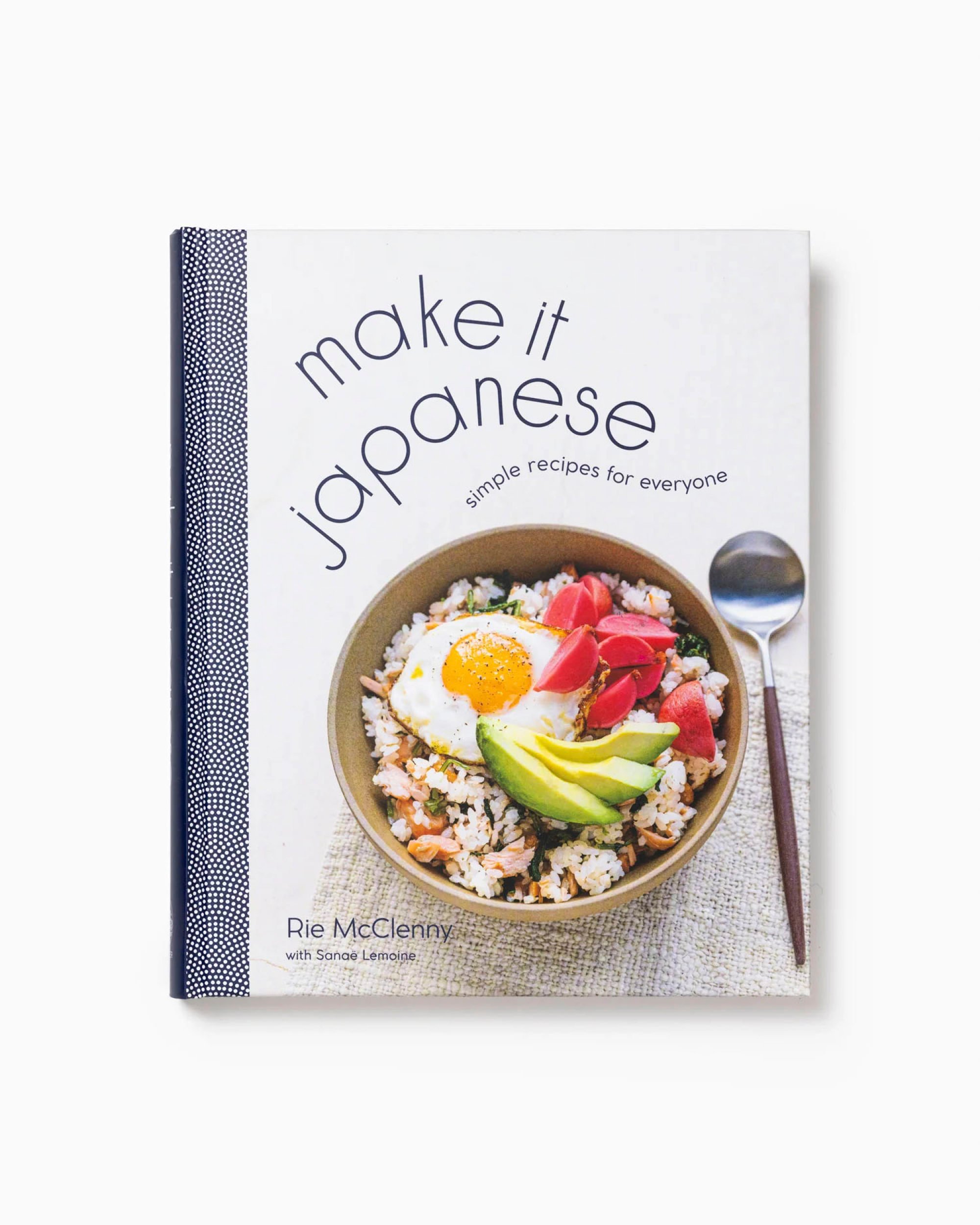

As McClenny recalls in her first cookbook Make it Japanese, they were absolute whizzes at folding dough wrappers around the savoury filling to create dumplings that were juicy and tender on the inside and, when fried, crispy golden-brown on the outside.

So good, in fact, that she never felt the urge to learn to make them herself.

“I enjoyed baking, and also enjoyed reading recipes in cookbooks and magazines,” she says from her home in the US city of Los Angeles, “but my mum was such a great cook I didn’t feel I needed to do it.”

While her mum imparted a few basics before she left home to go to university in Osaka, it was not until McClenny landed in a rural town in the US state of West Virginia during a year abroad that she realised reading about cooking is a sad substitute for actually doing it.

“There was only one Asian market, so I used what was available,” she says.

She found herself compromising once again with ingredients in her chase to conjure the flavours of her childhood during a post-university job at Disney World’s Japan Pavilion in Orlando, Florida.

They just want to learn how to cook. They are not learning English from me, but Japanese culture and food from a person from Japan

When the school asked her to open a patisserie cafe in New York in 2007, it proved to be a turning point in her career. Being surrounded by ambitious people who were following their dreams, she realised it was now or never.

“I just thought the food industry was so interesting,” she says, “so I started learning more and more. Students were so passionate about restaurants and bakeries.”

At age 33, she enrolled at the French Culinary Institute (now the Institute of Culinary Education), thinking she might become a food stylist.

She had so much fun and loved cooking so much that, after graduating, she became a chef instead, moving to Los Angeles with her husband to work as a chef at two Santa Monica restaurants.

She cooked professionally for three years before burning out one night after working more than 300 meals.

Deciding that a food media job would be less stressful (but still fun), in April 2016 she applied for a position as a recipe developer at Tasty Japan, the Japanese edition of BuzzFeed’s food media brand Tasty.

“But the more I did it, the more I realised people didn’t care so much,” she says. “They just want to learn how to cook. They are not learning English from me, but Japanese culture and food from a person from Japan.”

Despite the long hours to get there, she says, “it was exhilarating to finally pursue what I loved”.

Showing the beauty of Japanese cuisine on camera made her realise she wanted to show that “Japanese home cooking can be for everyone”.

So when a publisher reached out to her in 2021 to do a cookbook, she said yes, and started writing that same year, drawing on the nourishing food her mum cooked throughout her childhood for inspiration.

As she discovered in West Virginia so many years ago, with salt from soy sauce, acidity from sake and sweetness from mirin, “you can basically cook anywhere”.

While some of her offerings require time, many of the dishes in Make it Japanese will easily come together on a busy weekend night.

Most recipes are based on food she grew up eating or learned to cook once she moved to the US, using ingredients you can get at any supermarket instead of a speciality store.

Geared to those new to Japanese cooking, the book also includes instructions on how to stock a Japanese pantry and has a short chapter on essential Japanese cooking tools.

It is not only very traditional, she says, but shows exactly how she cooks at home. That includes a step-by-step recipe for her mother’s gyoza that discloses the secret ingredient that makes them so incredibly tasty – nira, or garlic chives. They are also known as Chinese leeks.

“You definitely don’t want to go on a date after eating them. They are so stinky,” McClenny says with a laugh.

Her mum’s recipe also includes seasoning the minced pork filling with grated ginger, soy sauce and sake and adding fresh shiitake mushrooms and lots of finely chopped cabbage for a bit of silky heft. “But every home has a different recipe,” she says.

She also makes the gyoza with a lacy, crispy crust on the bottom called “wings”, or hane in Japanese – created by adding a cornflour slurry to the pan while the dumplings are steam-frying.

They are served, with golden-brown aplomb, upside down on the plate, with a dipping sauce made from soy sauce, rice vinegar and sesame and chilli oils.

Although you can (and just might) make a meal of them, gyoza in Japan are almost always a side dish, says McClenny.

They are also made with super-thin premade wrappers in Japanese homes because these are easy to find in any grocery store. Plus, a recipe makes so many of them, and stuffing and folding the dumplings just so – gathered on one side and flat on the other – takes time.

So why complicate matters by adding home-made dough to the equation?

That said, even with premade wrappers, it might take beginners a lot of practice before their fingers develop the requisite muscle memory to fill, fold and pleat at a record pace.

“But don’t stress,” says McClenny. “It’s just practice. Channel your inner grandmother or mother, try your best and, if it doesn’t look great, it still tastes good anyway.”

Her one tip is to go kind of skimpy on the filling, with less than a tablespoon. “You feel like you want to fill a lot, but if you overfill it will come out.”

Once you get the hang of it, you will find gyoza are incredibly fun to make, even if they are not perfect.

“It’s just home cooking,” says McClenny. “Your family won’t judge you. They’ll be impressed you’re making [dumplings] from scratch.”

Gyoza with crispy ‘wings’

Serves six to eight people.

For the prettiest pleats, be careful not to overfill the wrappers. Adding a little cornflour slurry to the pan while cooking the dumplings will create a lacy, crispy crust on the bottom called hane – Japanese for wings.

Unless you are an overachiever, do not worry about making dough from scratch for these pan-fried dumplings.

Japanese gyoza are meant to be very garlicky, so if you cannot find garlic chives at your local Asian market, use the same amount of scallions or chives, but also add two grated garlic cloves to the filling.

Ingredients

For the dipping sauce

-

4 tbsp (¼ cup) soy sauce

-

4 tbsp (¼ cup) rice vinegar

-

1 tbsp toasted sesame oil

-

1 tsp chilli oil

For the filling

-

225 grams (8 oz) ground pork

-

90 grams (3 oz) finely chopped green cabbage

-

45 grams (1½ oz) finely chopped garlic chives (also called Chinese leeks)

-

35 grams ¾ oz) finely chopped fresh shiitake mushrooms

-

½ tsp finely grated fresh ginger

-

1½ tsp soy sauce

-

1½ tsp toasted sesame oil

-

1½ tsp sake

-

½ tsp salt

-

½ tsp freshly ground black pepper

For the dumplings

-

Cornflour or potato starch

-

35-40 gyoza wrappers

-

2 tsp neutral oil, such as canola or grapeseed

-

Salt

-

Toasted sesame oil

Method

Make the dipping sauce

In a small bowl, whisk together soy sauce, vinegar, sesame oil and chilli oil. The sauce will keep in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to three weeks.

Make the filling

In a large bowl, combine ground pork, cabbage, nira chives, shiitake, ginger, soy sauce, sesame oil, sake, salt and pepper. Using your hands, mix well to combine.

Make the dumplings

Dust a baking sheet with cornflour. Fill a small bowl with water.

Place a gyoza wrapper in the palm of your hand. Using the other hand, place a scant one tablespoon filling in the centre of the wrapper.

Dip your fingers in water and lightly wet one half of the wrapper’s rim. Fold the wrapper in half.

Using your fingertips, pleat only the top half of the wrapper, pressing against the bottom half to seal the gyoza. The bottom half of the wrapper remains flat; you only fold one side of the wrapper.

Place gyoza on the prepared baking sheet. Repeat with the remaining wrappers and filling. Sprinkle with more cornflour if the gyoza seem to be sticking together. Uncooked gyoza will keep in the freezer in a resealable plastic freezer bag for up to three months.

In a 10-inch non-stick skillet with a lid, heat two teaspoons neutral oil over medium heat. Add enough gyoza to fit in a single layer (about 12), arranging them in a circular pattern.

Cook until slightly golden on the bottoms, one to three minutes.

In a small bowl or measuring cup, combine 1/3 cup water, 1½ teaspoons cornflour and a pinch of salt. Pour cornflour mixture into the skillet.

Cover with lid and steam the gyoza until most of the water has evaporated, six to eight minutes.

Uncover and continue cooking until the water has completely evaporated and the cornflour has thickened to a gel-like web at the bottom of the skillet, about two minutes.

Drizzle some sesame oil around the edges of the gyoza. Increase the heat to medium-high and cook, uncovered, until the cornflour dissolves and dries, forming “wings” that are lacy and crispy, two to four minutes. Remove skillet from heat and let the gyoza rest in the skillet until any bubbling subsides, one to two minutes.

Using chopsticks or a spatula, loosen the “wings”. Place a large plate on top of the gyoza. Flip the skillet upside down to invert the gyoza onto the plate. Wipe the skillet clean and repeat with remaining gyoza.

Serve hot with dipping sauce.