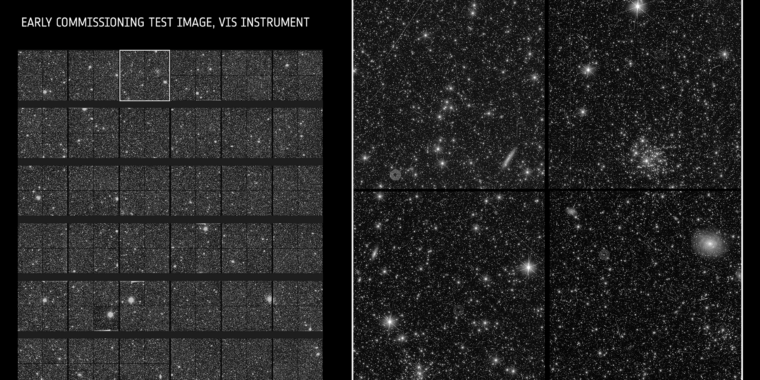

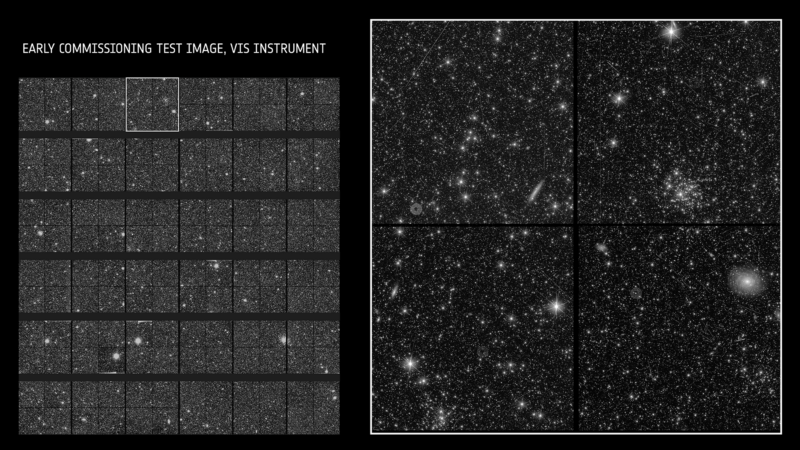

ESA/Euclid/Euclid Consortium/NASA

Nearly one month after launching into space, a European telescope has begun taking its first images and data of the Universe. And to the delight of scientists at the European Space Agency, everything seems to be working rather well.

As part of the months-long commissioning phase, both the telescope’s visual and infrared-light cameras have started snapping photos of the cosmos. Scientists who helped develop these cameras—VIS for visible light, and NISP for Near Infrared Spectrograph and Photometer—say the new instruments work superbly.

“We are very pleased that the commissioning phase of Euclid is progressing well,” Alessandra Roy, Euclid project manager at the German Space Agency at DLR, said. “The spacecraft will soon reach its final position at a distance of 1.5 million kilometers from Earth and begin scientific observations.”

Sized for a sky survey

The telescope has a primary mirror that spans 1.2 meters, or about half the size of the Hubble Space Telescope. Unlike Hubble, however, Euclid was not designed to focus on single galaxies or stars or other astronomical phenomenon in great detail. Rather it is intended to look at broad areas of the sky to obtain a more comprehensive view of the cosmos. Over its six-year life, the telescope will survey about 36 percent of the sky.

Euclid will observe large swathes of the universe to detect the shapes of galaxies and attempt to observe distortions that may be caused by mysterious, hidden matter. Scientists believe that only about 5 percent of the matter in the Universe is stuff we can look into the night sky and see—stars and galaxies, mostly.

So what does that leave? That’s the primary question Euclid is attempting to answer. Over the last two decades or so, scientists have come to understand that dark or hidden matter makes up about 25 percent of the Universe’s mass. The remaining mass, more than two-thirds of the cosmos, is something called dark energy, a presently unknown force that is causing the expansion of the Universe to accelerate.

Designed for dark energy

Understanding what dark matter is actually made of, or even confirming its existence, would represent a huge step forward in physics and cosmology, the study of the cosmos. Physicists are also keen to better understand the nature of dark energy, which can only be inferred by its effect on the rapidly expanding Universe.

When it is fully calibrated, Euclid will literally observe billions of galaxies in the night sky and provide data to create a three-dimensional map of the Universe. Euclid is one of the first space-based telescopes designed after the discovery of dark energy, so scientists hope it will provide critical data to shed light on such mysterious subjects.

“It is fantastic to see the latest addition to ESA’s fleet of science missions already performing so well,” said Josef Aschbacher, the space agency’s director general. “I have full confidence that the team behind the mission will succeed in using Euclid to reveal so much about the 95 percent of the Universe that we currently know so little about.”

The European Space Agency and its partners, including NASA, will continue to test and check out the telescope and its scientific instruments over the next few months, continuing the commissioning process. After verifying that all is well with the telescope after its launch and deployment in space, the science phase of the mission will begin in earnest late this year.