By Lee Hae-rin

In the bustling heart of Seoul, the South Korean capital, against the scenic backdrop of Mount Nam, is Sopa-ro – a hillside drive lined with an array of restaurants, all offering the same menu featuring giant-sized Korean tonkatsu.

Tonkatsu is a portmanteau of ton, meaning pork, and katsu, a simplified Japanese pronunciation of cutlet.

The tonkatsu served in these restaurants in Namsan, the Korean name for Mount Nam, is the same as the classic version found in other snack stands across Korea.

The pork is flattened until it spans the width of the plate, then breaded and deep-fried to a golden crisp and served with sweet brown sauce. A bowl of plain cream soup, white rice, cabbage salad and kimchi are served with each tonkatsu.

These restaurants all label themselves as tonkatsu restaurants on their signboards, although they sell many other Korean dishes like soup and stew.

Seoul food guide – how to eat your way around South Korea’s capital

Seoul food guide – how to eat your way around South Korea’s capital

The dish arrived in Korea through the Japanese influence during colonial occupation in the 1930s and 1940s, some decades after the Western dish was introduced in Japan at the end of the 19th century.

It was only in the 1960s that Western cuisine became popular in Korea, but it took even more time for tonkatsu to become popular with the Korean public, according to food columnist Park Chung-bae.

“At the time, when most Koreans had a hard time making a living, fried pork was not a popular dish for the public,” says Park. “Western cuisine was a luxury in dining out, a fancy dating course for a young couple.”

However, the trend changed as the ingredients for the fried pork became more available in the rapidly developing country, Park says.

The pork industry grew rapidly in the 1950s because of rising demand for imports from Japan in the 1950s, while a nationwide campaign to consume more flour-based food to counter a rice shortage in the 1960s made wheat flour more available in the market.

I just keep making tonkatsu, every day, day and night. I just keep doing my job

In addition, the mass production of cooking oil started in the 1970s with the rise of a food maker, Dong-bang-you-ryang, today known as Sajo, he explains.

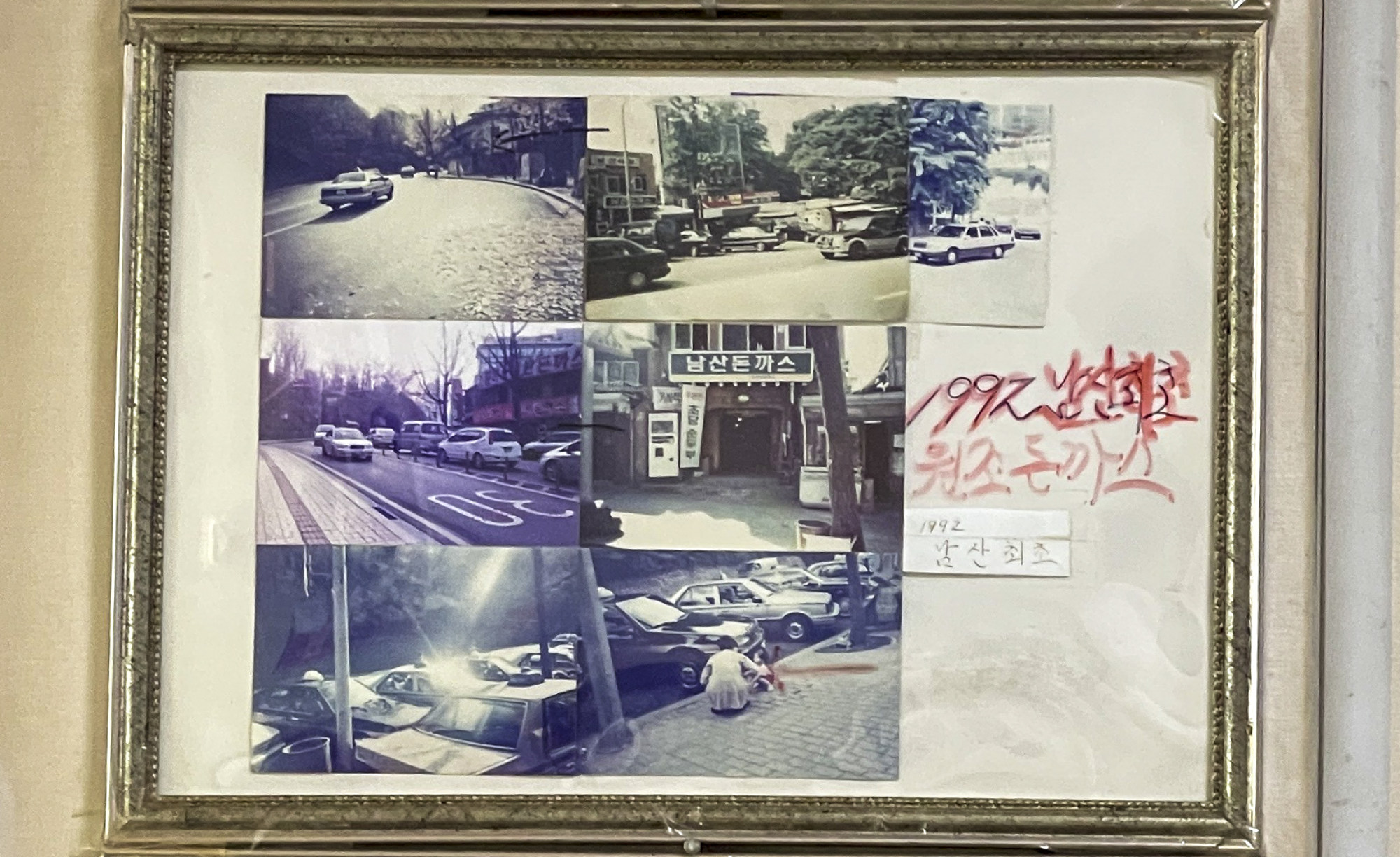

Tonkatsu’s real breakthrough on Mount Nam came thanks to taxi drivers. The first places to serve tonkatsu in the area were originally restaurants catering to drivers, located near taxi garages down the mountainside.

Park Je-min, 62, who owns one of the first restaurants to serve tonkatsu in Namsan, says he originally served soft tofu stew for taxi drivers over 30 years ago.

It was an immediate success.

Park’s restaurant quickly saw lines of taxis parked along the street as drivers flocked to try the fancy Western dish at an affordable price, and neighbouring restaurants started doing the same.

Weary of wagyu? How about Hanwoo? All about the Korean luxury beef

Weary of wagyu? How about Hanwoo? All about the Korean luxury beef

According to 72-year-old taxi driver Yu Gil-jun, his first tonkatsu “tasted like heaven”.

The dish recently resurfaced on the foodie radar when it is featured in Disney+ Korean original series Moving, especially among the young generation unfamiliar with the history of Namsan tonkatsu.

For newcomers and regular visitors alike, the hillside restaurants continue serving tonkatsu.

One of the most cherished memories of serving tonkatsu in Namsan over 30 years is seeing the big smiles on the faces of customers, Park says.

“So I just keep making tonkatsu, every day, day and night. I just keep doing my job,” he says, trimming cabbage that will be served with the dish.