“It was what you call an ego death, when everything that you’ve defined yourself by just doesn’t work any more, and it’s not going to carry you any further. You’ve got to redefine yourself; you’ve got to be reborn as a different person or die.”

As she picked up the pieces, Chan instinctually turned to writing, and her words became a vessel for healing in a way that she had not expected.

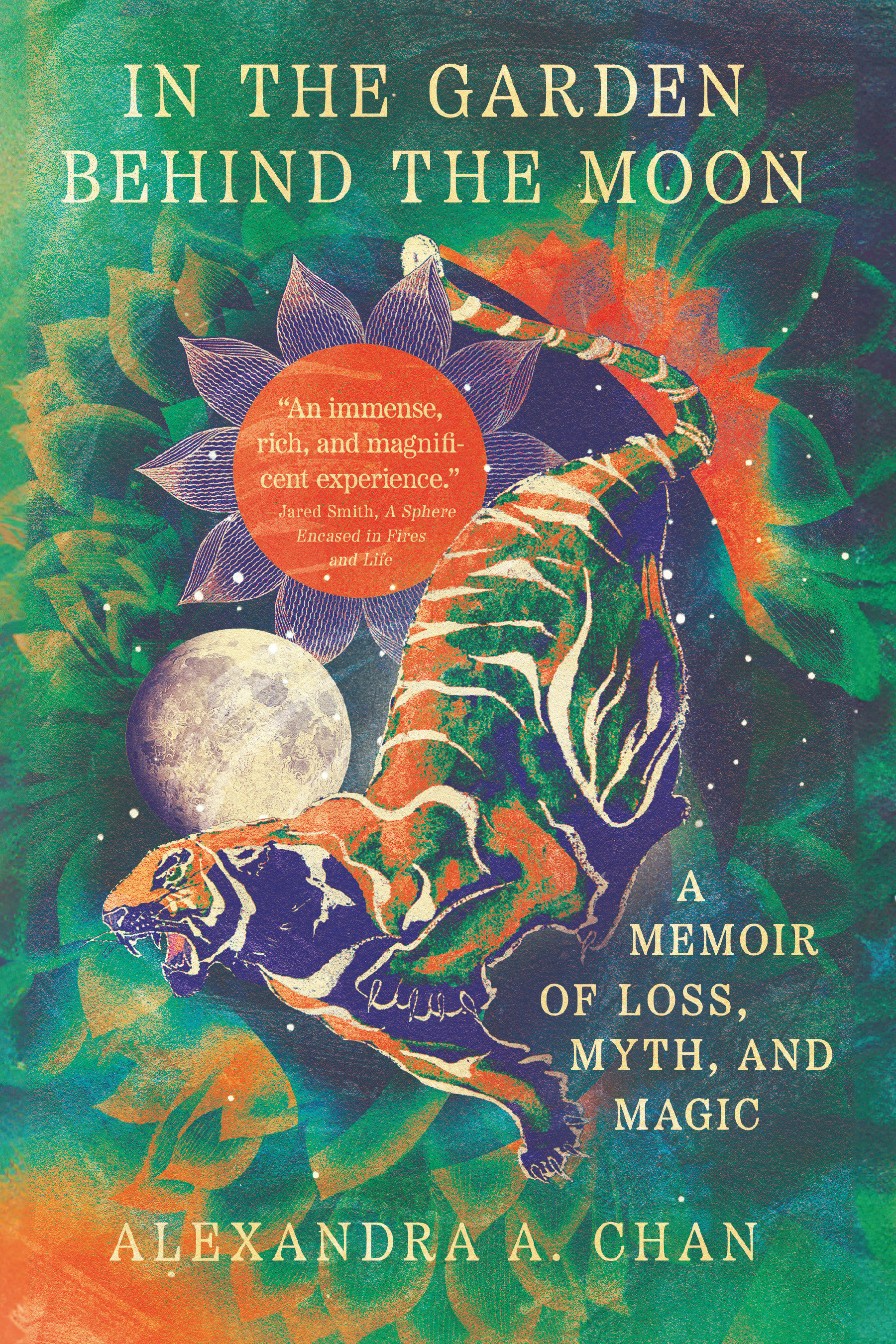

Today Chan has distilled her journey into a book, In the Garden Behind the Moon: A Memoir of Loss, Myth, and Magic. As its title suggests, the book is a string of Chan’s memories and family stories, but an undercurrent of myth and magic is ever present.

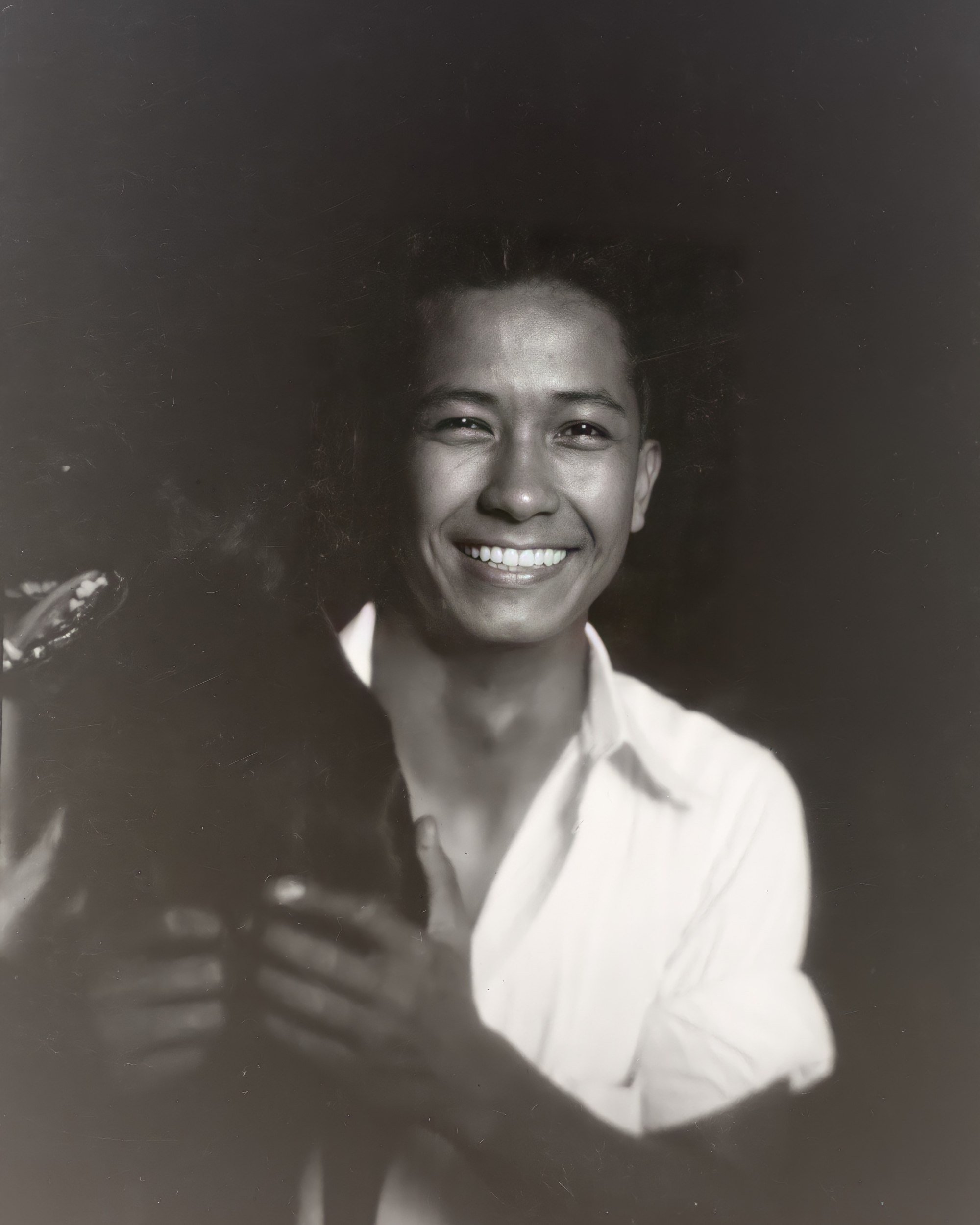

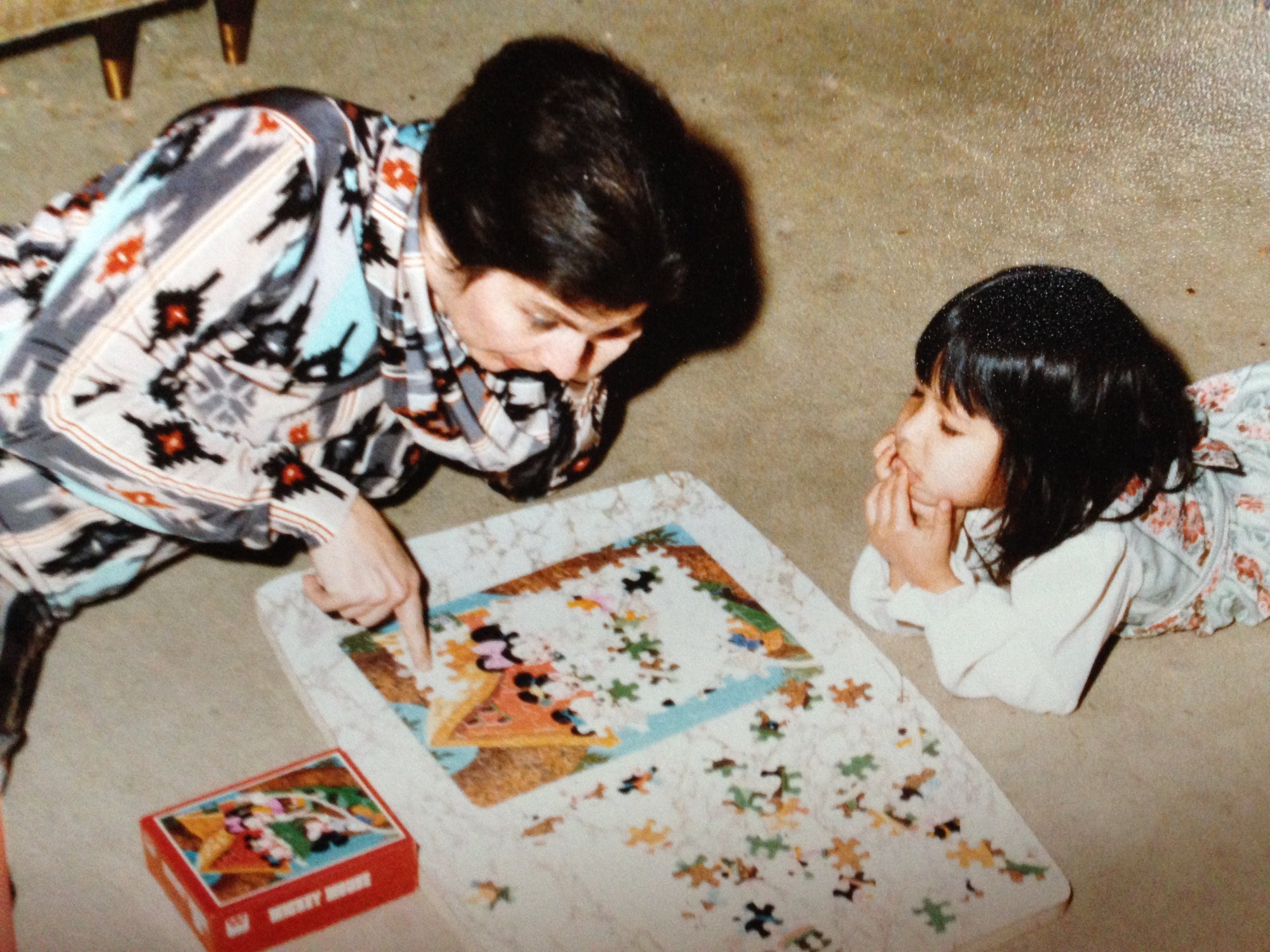

An archaeologist by trade, Chan grew up in the 1970s and 80s, part of “the last generation before the internet took over”, as she puts it.

“I was always sort of in between worlds,” she says, “both within my own family, being interracial, but also in society, being sort of an island in this mostly white town.”

Unlike others who came from immigrant families, she did not struggle as much with her Asian identity.

“I can’t really relate to that part because for whatever reason, being part of the Chan clan, as they called it, inoculated me,” she says. “I felt it made me really special. Why would you not want to be a Chan? That [would be] ridiculous.

“I had a very strong sense of inner bigness, importance and value that I think came from that family.”

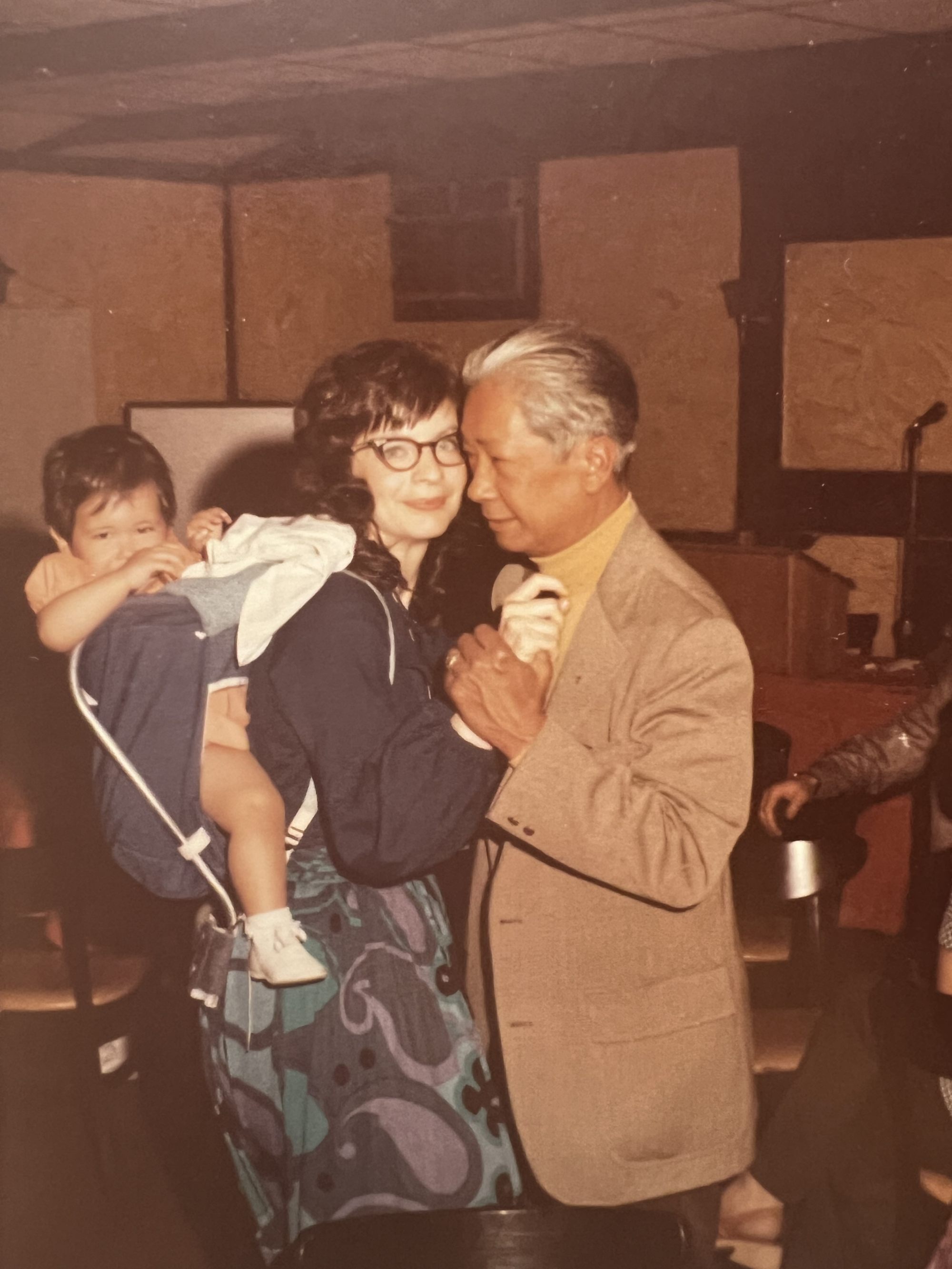

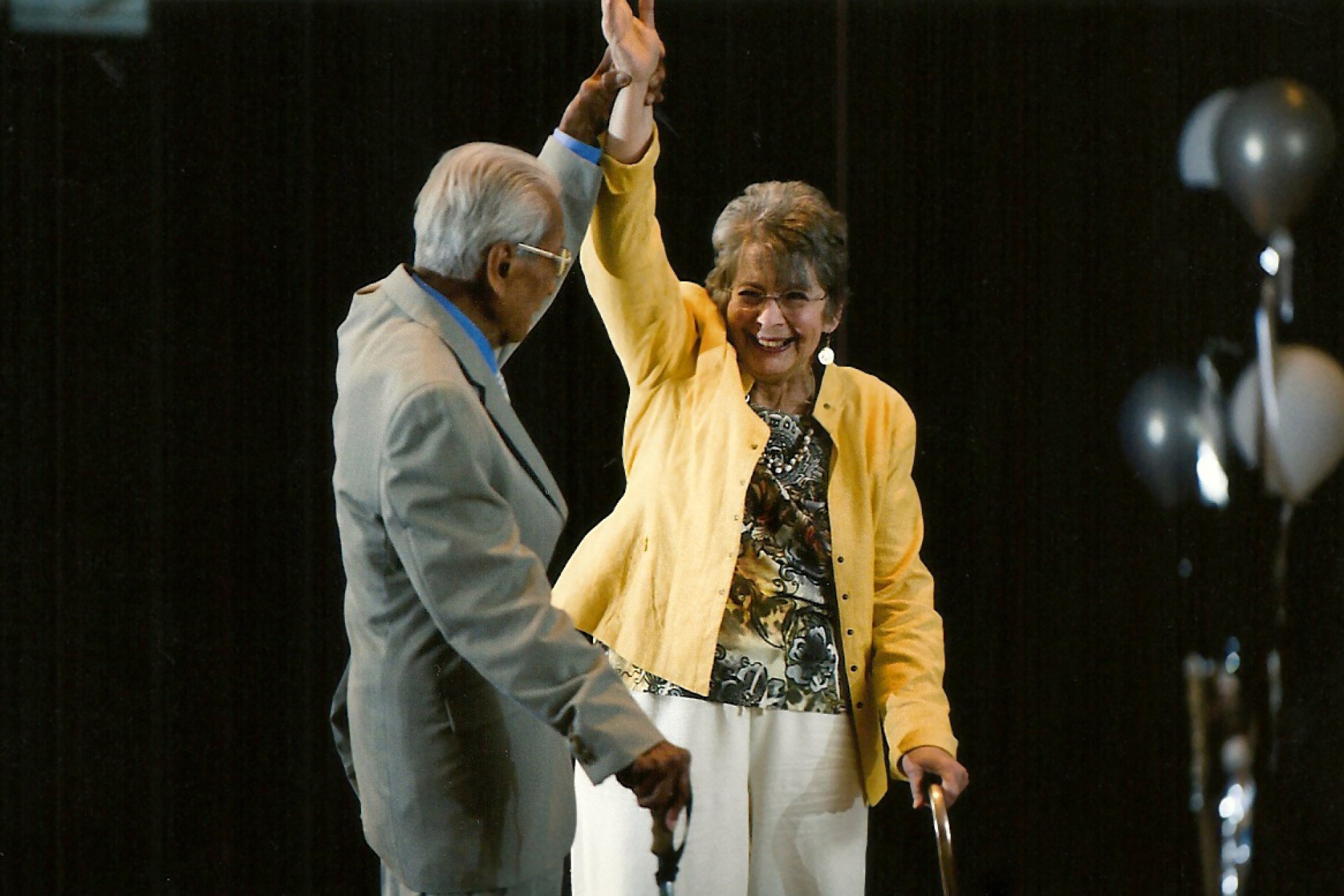

When she was born, her father was 59 years old, and “my mom was an executive – one of the first female coders and Kodak executives – which was very rare for women [back then]”, Chan explains.

So she and her father developed an inseparable bond, and Chan grew up being treated to stories of his remarkable feats.

In her book, Chan writes: “His presence in my life was planetary; I was but one of his moons. Or was he a star, the light of his life making my own feel twinkly and charmed?”

Aside from work, at home, “he was also so charming, witty, warm and wise, and he was uniquely gifted with children”, says Chan. “I refer to him in my book as my ‘personal colossus’.”

Chan’s mother, Karen Elizabeth Smith, was the first of her parents to die, from multiple myeloma, a blood cancer, in 2011. Four and a half years later, when her father died, “It really just all crashed on me all at once,” says Chan.

“Maybe I hadn’t fully processed grief for my mom, because I was so busy trying to make sure that my dad was OK, that when he died, it felt almost like I lost them both together. But what was still intact were these creative urges that I’ve always had.”

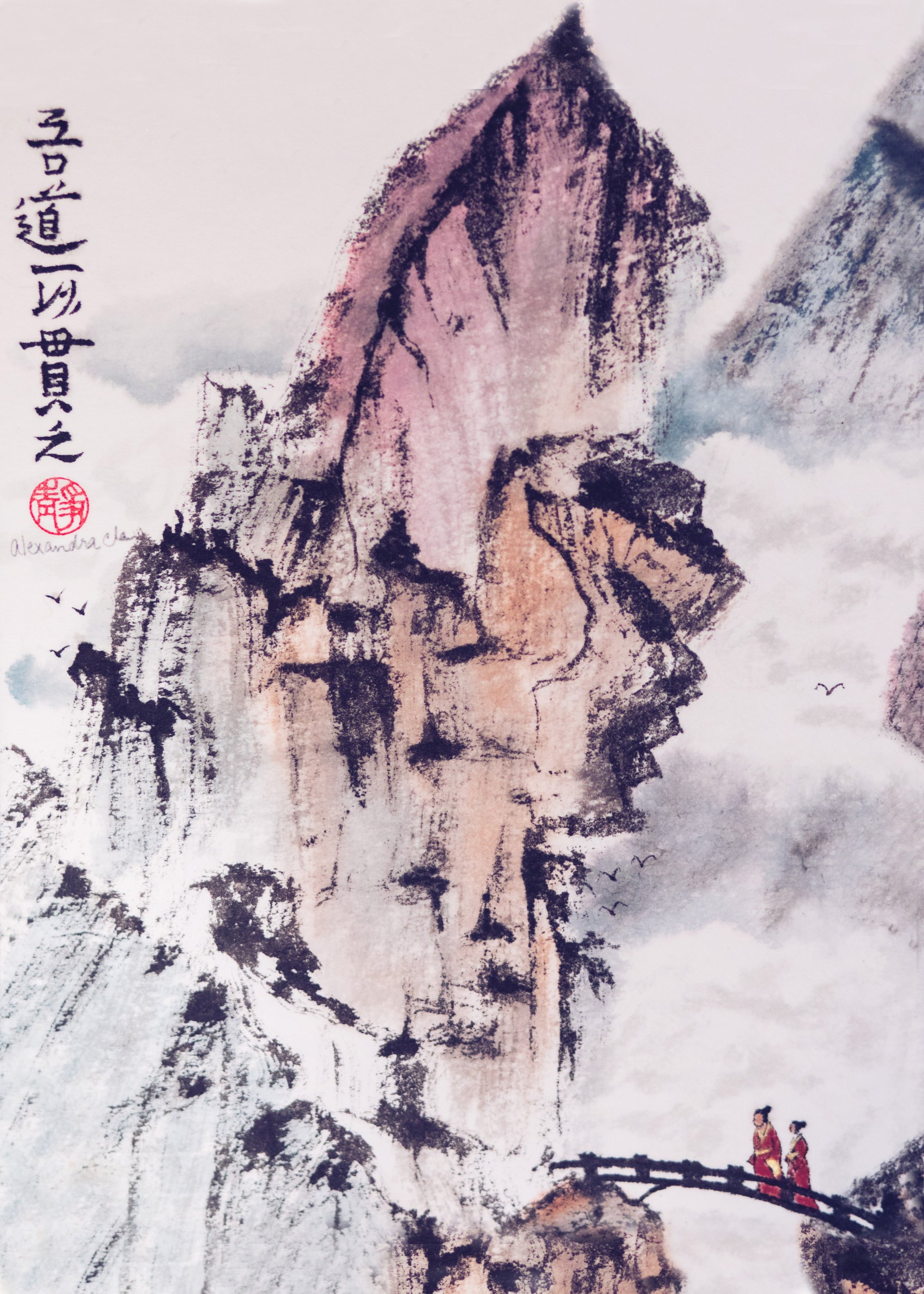

So in her grief, she fell back on the only things she felt she could do: playing music, writing and painting, the latter of which she took up in 2015.

“I felt so presumptuous to think that I could do that a year after my first lesson, but it was like it was waiting in the wings, fully formed,” says Chan.

“It gave me a whole new channel to access my stories, because through these archetypal energies – animal and human – of the paintings, you can tap into a sense of myth.

“You can tap into these deeper, broader understandings of your own circumstances; you can start seeing your circumstances in a more artistic and metaphorical way.”

Chan’s brush paintings are scattered throughout In the Garden Behind the Moon. Among them are her “Two Scholars” series, a nod to a Buddhist philosophy that “the obstacle is the path”, part of Chan’s internal musings as she navigated her grief.

Compared to her online shop, the book took a little longer to come into being.

About a year after he died, I had an epiphany, and I realised I wasn’t writing a book about him. I wasn’t writing his story, I was writing my own

Alexandra Chan

“I’ve always been drawn to stories [but] I did not foresee becoming a writer or an author in any way,” she says. “Even after writing my first book [Slavery in the Age of Reason: Archaeology at a New England Farm; 2007], an academic publication about the archaeology of northern slavery, I still hesitated to call myself an author, because I felt like it was just a necessary by-product of the work that I’d been doing.

“When you do that kind of important research – slavery in the north – you can’t sit on it,” says Chan. “The world is counting on you to make it public and accessible to everyone.”

On the other hand, In the Garden Behind the Moon was “definitely the most vulnerable thing I’ve ever done”.

Over the years, friends had remarked that she should write a book about her father, but she says she never considered doing so because he was against the idea: “He always had the same thing to say, which is, ‘Nobody’s going to write a book about me.

“If anyone’s going to write a book about me, it’s going to be me, and I’m not doing it, so there.’ I couldn’t forget those words. They just kept ringing in my head, so [they] really prevented me from exploring that too much.

“The turning point for me was, about a year after he died, I had an epiphany, and I realised I wasn’t writing a book about him. I wasn’t writing his story, I was writing my own. Therefore, the problem of how to tell another man’s story has been rendered moot.”

That said, there was a time when Chan had thought the purpose of her writing was not to publish it but to simply heal herself.

“[I thought] maybe that is, in itself, a worthy thing – maybe it’s OK if I never see this published,” but fast-forward three years and a book deal later, “I’m glad that that’s not the case.”

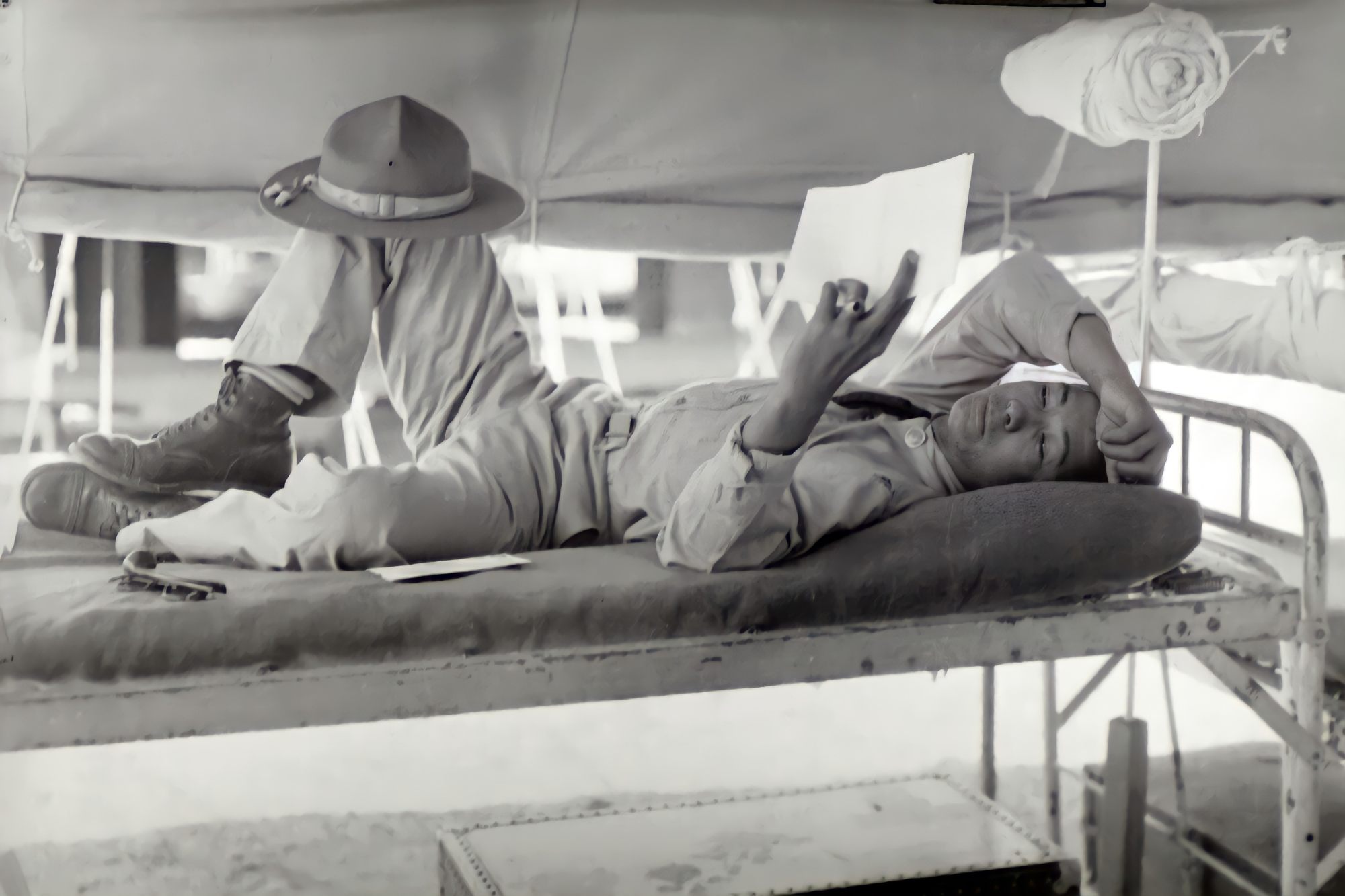

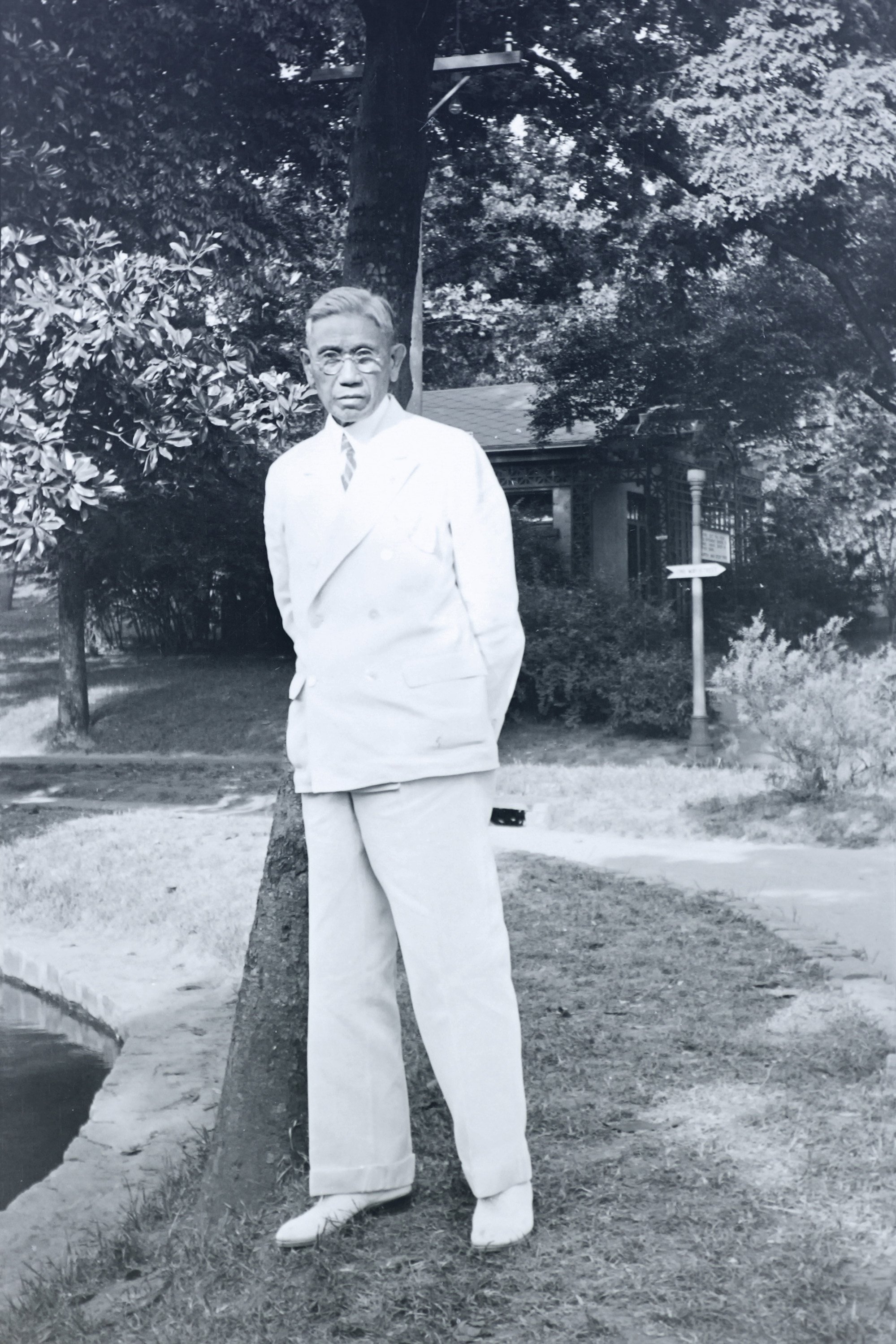

Set in Guangdong province, the prologue to In the Garden Behind the Moon introduces the person who is perhaps the true originator of the Old Chan Magic, Chan’s grandfather, Chung T’ai Peng (later known in the US as Robert Chan).

Named after Peng, the mythological creature who transforms from a Kun fish to a giant bird, Chan’s grandfather was a poet and hoped to become a Confucian bureaucrat.

After a hiccup that involved Chan’s grandfather being stranded at sea with two captors – sailors from an imperial ship who he eventually threw overboard – he found passage to San Francisco, and later made his way to Savannah, Georgia, where he became the owner of a Chinese laundromat.

His oldest son, Archie, was the first Chinese-American baby born in the state of Georgia.

“He was, on the surface of things, totally powerless in this society,” explains Chan. Through acting as a goodwill ambassador for the Chinese community, however, he was eventually able to “idiosyncratically desegregate the Savannah school system 30 years before Brown vs Board of Education”.

“He would order a Chinese Christmas box every year that was filled to the brim with things that the kids wanted for themselves, but it wasn’t for them, it was for judges, lawyers, teachers and business leaders in the community,” says Chan.

“They were gifts of goodwill to create relationships because he didn’t have the protections of citizenship. So I wonder: how many games of poker? How many porcelain vases and [pieces of] jade jewellery did he have to disperse to get permission from authorities to send his Chinese children to the public white school?

“It surely must have come down to charisma. In Savannah at that time, there was no high school for non-whites, not even a segregated one.”

For each, Chan has written an introduction to the animal and its horoscope, which in turn corresponds to a story from Chan’s life.

For example, the first “book” opens with a passage on the ram, which portends: “Is it misfortune or destiny that I am an Ox – same as Dad?

The chapter then details Chan succumbing to the reality that her father is dying, before shifting the scenery to Iceland, where a family trip manages to lift her sorrow.

The book is not just about her father’s death, however, as much of the first quarter is dedicated to her mother. “Have I overlooked her to an extent myself? Why couldn’t I have been the daughter for her that I was for Dad?” Chan writes in the book.

Later chapters touch on a multitude of topics, from Chan’s travels to her father’s war letters to his first wife, Gretchen. There are also mentions of an interview with Chung that was conducted by the Federal Writers’ Project, a government initiative launched by then-US president Franklin D. Roosevelt that saw out-of-work writers interview ordinary people in various states to develop a self-portrait of sorts for America. (Chung’s interview was aptly titled “Laundryman”.)

And while the memoir may begin with grief and loss, it ends with a reflection on how generational trauma – born from Chung’s escape from China – affected Chan’s ability to reconcile with her parents’ deaths.

“It was a wild ride, realising that a lot of what had kept me caught in this severe grief over the death of my parents, and what prevented me from carrying that grief more lightly, was rooted in old refugee trauma – old pain that wasn’t necessarily even my own,” she says, adding that she had been carrying “a spectral suitcase that should have been thrown back into the South China Sea 140 years ago”.

“This feeling of unbelonging: where is my home? Who are my people? I attributed it all to the loss of my parents and the dissolution of my immediate family structure, but by the end of the book, I begin to realise that there’s more at play here.

For Chan, this understanding cast new light on the source of the Old Chan Magic. While writing, the author reflected on her father’s vulnerabilities, which matched her own sense of not belonging.

As a mixed-race boy growing up in the Jim Crow South, she says, her father must have wanted to overachieve, to control his own destiny, perhaps unlike his own father when he was forced to flee and never return.

“I began to understand: what if Old Chan Magic isn’t just a gift, it’s also something that these kids – my father and his siblings – felt compelled to conjure because of refugee trauma, because of growing up in the Jim Crow South?

“This is where the generational pain comes in, because their father was ever the reluctant exile. He never fully accepted the fact that he could never go back to China; he always wanted to go home and he never could.

“And that was a source of pain for him all the way to the end.”

Despite the subject matter, the overarching feeling one gets from reading Chan’s memoir is a sense of wonder and hope, which mirrors the rediscovery of magic that the author felt while writing the book.

“I was feeling this alchemical response in myself,” says Chan. “When I write about the people I love, it makes them feel like they’re alive. So I felt like I was spending time with them that way.

“But gradually, I began to understand that I was writing myself to wellness through this really magical process, and I was beginning to see the world differently and be in the world in a much easier, more beautiful way.”