Aurich Lawson | Getty Images

Welcome back to our series on how Ars Technica is hosted and run! Last week, in part one, we cracked open the (virtual) doors to peek inside the Ars (virtual) data center. We talked about our Amazon Web Services setup, which is primarily built around ECS containers being spun up as needed to handle web traffic, and we walked through the ways that all of our hosting services hook together and function as a whole.

This week, we shift our focus to a different layer in the stack—the applications we run on those services and how they work in the cloud. Those applications, after all, are what you come to the site for; you’re not here to marvel at a smoothly functioning infrastructure but rather to actually read the site. (I mean, I’m guessing that’s why you come here. It’s either that or everyone is showing up hoping I’m going to pour ketchup on myself and launch myself down a Slip-‘N-Slide, but that was a one-time thing I did a long time ago when I was young and needed the money.)

How traditional WordPress hosting works

Although I am, at best, a casual sysadmin, having hung up my pro spurs a decade and change ago, I do have some relevant practical experience hosting WordPress. I’m currently the volunteer admin for a half-dozen WordPress sites, including Houston-area weather forecast destination Space City Weather (along with its Spanish-language counterpart Tiempo Ciudad Espacial), the Atlantic hurricane-focused blog The Eyewall, my personal blog, and a few other odds and ends.

As hosted apps go, WordPress is less fussy than most, being one of the most widely used web applications on planet Earth. If one is self-hosting, it takes more time to configure the web server and the PHP handler than it does to configure WordPress—you just download a zip file, uncompress it into your webroot, and browse to the proper URL. Specify your username and your MySQL information, and boom, you have a WordPress website ready to go!

In terms of functional flow, self-hosted WordPress requires basically four things:

- The WordPress PHP application itself

- A web server application, like Apache or Nginx, to actually serve things to the visiting reader

- A PHP handler, like php-fpm, to run the PHP code and create things for the web server application to serve

- A database for WordPress to store posts and other WP stuff in

In addition, the host on which you’re running WordPress needs to provide the following resources to let those applications actually have a place to function:

- Some amount of RAM

- Some amount of CPU time

- Some amount of disk space to hold our application’s code

- Some additional amount of disk space to hold our database

- Some additional additional amount of disk space to hold data created by our application users (like uploaded files)

- Some kind of network connectivity to the outside world

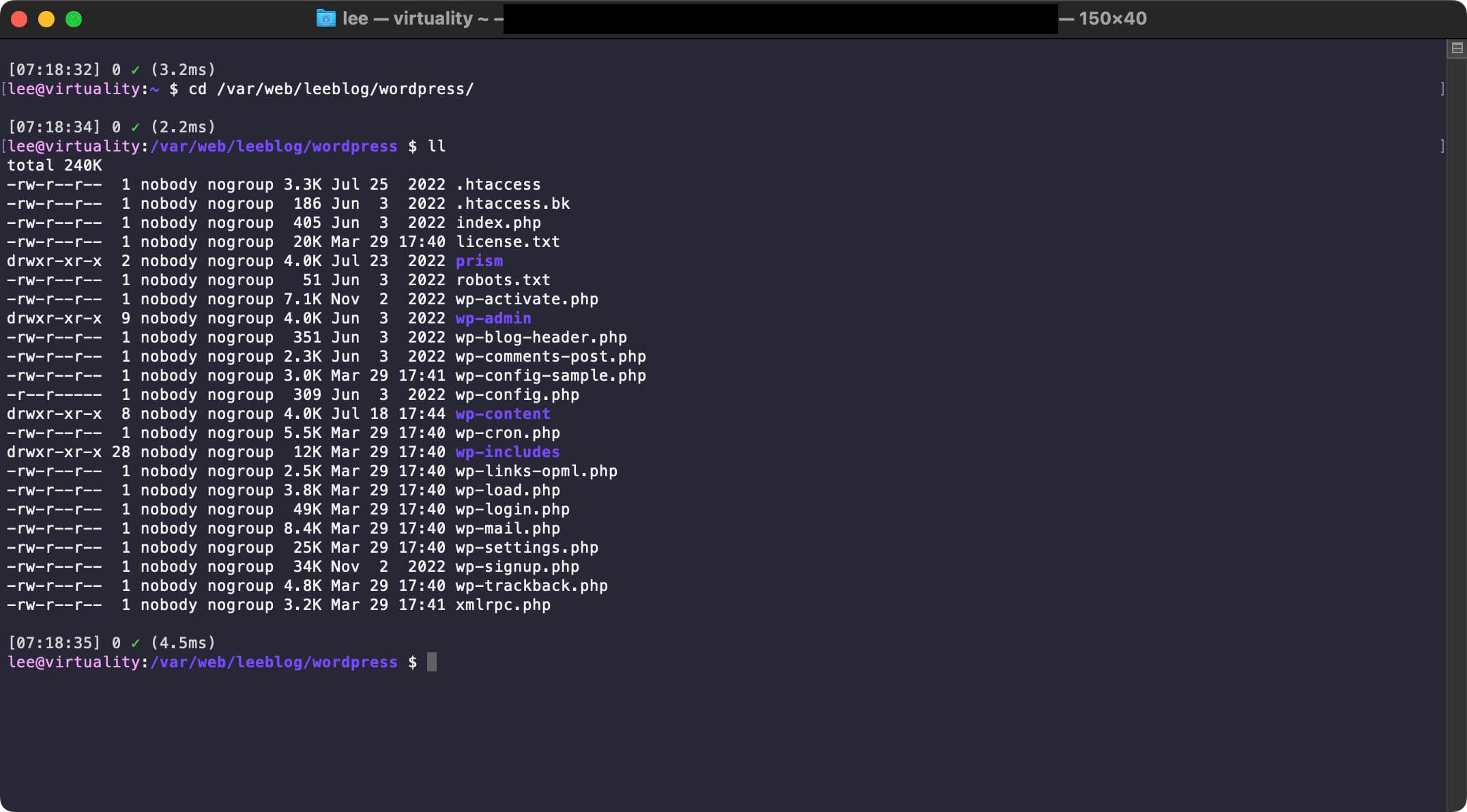

When it’s installed, WordPress exists primarily as a collection of tables in a MySQL database and a pile of files in your web root directory. My personal blog’s WordPress root directory, for example, looks like this:

Lee Hutchinson

Not terribly exciting. And there are no executable binary files in here or anything—they’re mostly just PHP files and require the magic of a PHP handler like php-fpm to actually run them. Otherwise, they just sit there.

The process of actually running those PHP files works like this: Let’s say you want to view a story on Ars Technica—like, say, this one. You click that link, and your web browser sends an HTTP GET request that, through the process described in part one, eventually arrives after a few milliseconds at the Ars Technica web backend. (To get specific, the request is serviced by one of the Nginx processes inside one of the many running arx-production-web-apps tasks).

Nginx looks at the path in the URL and figures out which part of it corresponds with the post you’re asking to view, then tells php-fpm to begin executing PHP code from the WordPress index.php file, using the requested post as a parameter. The php-fpm process also causes queries to be run against MySQL—in this case, it pulls the requested post’s text and structure from the database. Additionally, php-fpm pulls URLs for images from the database so that your browser can request those images from our CDN. (A CDN, or “content delivery network,” is a service that caches your stuff for you in lots of different places so your site will load faster—at least in theory.)

This all happens quickly, and it all happens within the confines of a single server—be it a physical box, a VPS, or whatever else you have. If we take away the server to contain all this within, how does it all hang together?

The short-short version is it hangs together because we use the tools from part one, and apparently, it all works because you’re reading these words right now. Science!