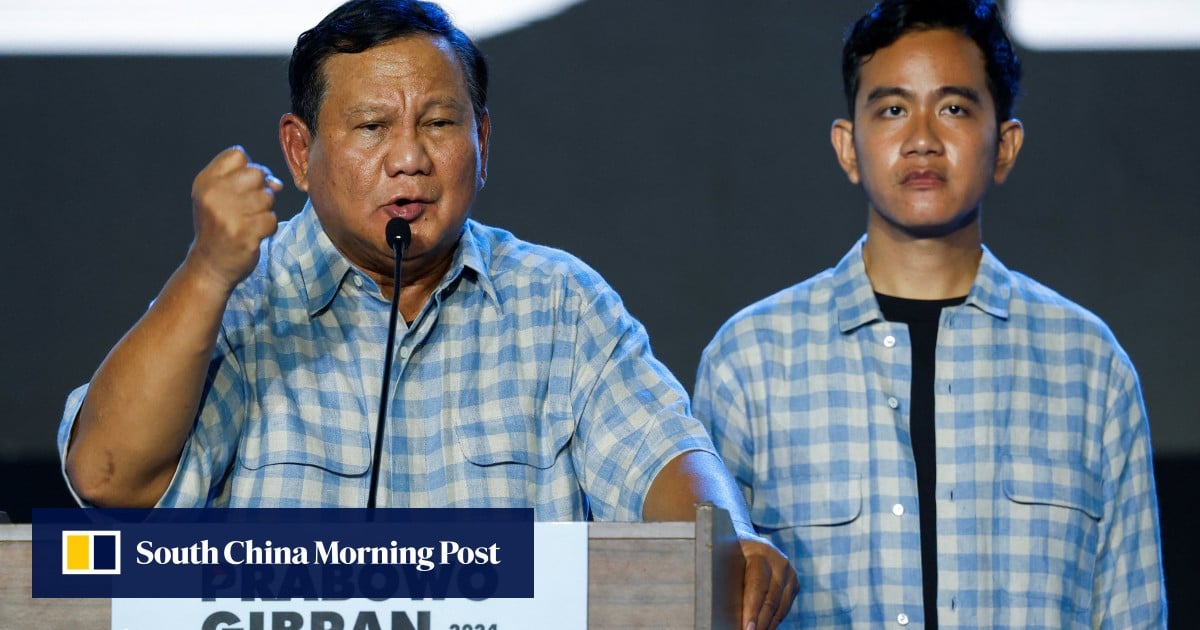

In a victory speech to supporters on Wednesday night, Prabowo said: “All survey institutions, including institutions that are on the sides of other candidate pairs, show figures that the Prabowo-Gibran pair won in one round.

“Gibran and I said, although we are grateful, we should not be arrogant. We can’t be proud. We must not be euphoric. We must remain humble, this victory must be a victory for all Indonesian people.”

This was the 72-year-old’s third campaign to lead the country after losing two bitterly contested presidential races in 2014 and 2019, both times to Widodo. Still, the president named Prabowo as his defence minister in 2020.

During his current campaign, Prabowo’s pick of Gibran as his running mate signalled to voters he would maintain popular Widodo policies if he were to clinch the top job.

With the president’s tacit support of the pair, Prabowo surged ahead of his rivals in opinion polls before the race, making him the runaway candidate to win the election.

Arya Fernandes, head of the politics department at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Jakarta, said there was a very strong chance Prabowo would continue Widodo’s policies.

“But it is also hard to say. He may go in another direction,” he added.

Indonesia election 2024: everything you need to know

Indonesia election 2024: everything you need to know

A combative career

If confirmed, Prabowo’s presidency would mark the apex of a military and political career that has spanned more than 50 years.

After graduating from the Indonesian Military Academy in 1970, Prabowo served in the Special Forces (Kopassus) before being tapped to lead the Strategic Reserve Command (Kostrad) in 1998.

That same year also saw the economic and political crisis that led Prabowo’s father-in-law President Suharto to resign after 32 years of dictatorship. Around the time of the riots that precipitated Suharto’s ouster, troops under Prabowo’s command kidnapped and tortured at least nine democracy activists. Prabowo acknowledged responsibility for the incidents and was dishonourably discharged from the military.

He was banned from the United States for decades due to alleged human rights abuses, including military crimes committed during the occupation of East Timor, but the sanction was lifted after Widodo named him defence minister.

After his military career, Prabowo focused on politics, forming the Great Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) party in 2008. He ran as the vice-presidential candidate to Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) chairwoman Megawati Soekarnoputri in 2009 and they were defeated by incumbent president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

Who are the 3 candidates vying to be Indonesia’s next president?

Who are the 3 candidates vying to be Indonesia’s next president?

During his 2014 and 2019 presidential campaigns against Widodo, Prabowo painted himself as a military strongman through fiery speeches brimming with nationalist rhetoric.

He initially refused to concede defeat after the 2019 vote, insisting a count by his team showed he was winning. This led to his supporters alleging the polls had been rigged, culminating in riots in Jakarta, during which eight people lost their lives. Prabowo finally relented after the Supreme Court rejected his appeals against the election result.

Prabowo’s appeal this election goes beyond his supposed alliance with Widodo. Arya from CSIS said a survey conducted by his think tank in December found that young Indonesians were increasing seeking strong, assertive leaders.

“This is part of a trend we are noticing across the world, and it seems to be the case for the Indonesian public. Prabowo appears to be seen as the strong leader figure,” he said.

Prabowo’s nationalistic agenda?

While a large percentage of his voters appear to have a desire for Prabowo to maintain Widodo’s policies, he has hinted that he could take a more nationalistic approach to foreign affairs than his predecessor.

Prabowo’s election manifesto indicates that the former general would be focusing on turning Indonesia into a “strong country”. According to the manifesto, Indonesia will be a country “respected in international relations” and one that has “a well-managed defence and security that can protect the nation and ensure peace in its territory”.

Arifianto from RSIS said that given Prabowo’s military background, it would be no surprise he aspired to make Indonesia powerful not just economically but also militarily.

“He is probably going to continue to seek to boost Indonesia’s defence spending, to make the Indonesian military into one of the largest armies in the region. Whether the other trade or regional powers respond well to this is a big question,” Arifianto added.

Indonesia election 2024: is Prabowo poised for a first-round win?

Indonesia election 2024: is Prabowo poised for a first-round win?

“The West teaches us democracy, human rights … but the West has different standards … There’s a shift in the world. Now we don’t really need Europe any more.”

He also accused the EU of “unfair” treatment over tariffs imposed on Indonesian exports such as palm oil.

When questioned whether Indonesia would side with China or the US in their rivalry, however, Prabowo stressed Jakarta’s “neutrality”. He said he respected the US for its contributions towards Indonesia’s independence as well as China’s contributions to the Indonesian economy.

Sana Jaffrey, a research fellow at Australian National University specialising in Indonesian politics, said that while Prabowo has made some “anti-foreigner, highly nationalist statements” on the campaign trail, she’s also “heard that he’s given assurances to foreign diplomats in private that he’s not going to be unfriendly to foreigners, that he’s very open to investment, that he’s going to have good relations.”

“So I think what we might have seen in the public is more to bolster his image as a nationalist, and it’s part of his brand. But he has, from what we’ve heard, said different things in private,” Jaffrey added.

Legislative hurdles

Regardless of his agenda, Prabowo is expected to be busy initially with building his coalition partners for an administration and soliciting support for his policies.

Widodo managed to set up a large coalition that has given him the ability to pass his most ambitious policies, including the US$32 billion plan to move the country’s capital from traffic-clogged Jakarta to a new city in Eastern Borneo.

However, Widodo’s coalition was possible in large part due to his affiliation with the ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P). By backing Prabowo instead of PDI-P’s own candidate in Wednesday’s election, former Central Java governor Ganjar Pranowo, Widodo may have alienated an important segment of parliament for Prabowo.

“It is hard to see PDI-P joining Prabowo’s cabinet, so you might have a presidency that is quite personalised in terms of power, in terms of how he handles policy,” said Noory Okthariza, a political researcher with CSIS.

“At the same time, you also have quite a robust opposition group that may comprise different parties, as opposed to Jokowi’s time, where it was mainly only the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) that sat in opposition,” Noory added, referring to a conservative Islam-based party that has often challenged Widodo’s agenda.

Noory said PDI-P might join PKS in the opposition, along with some other factions including the NasDem party and the National Awakening Party (PKB), another Islam-based party, which could create a more serious challenge to Prabowo’s legislative priorities.

With uncertainty on how the parties will realign themselves following the vote, the only thing that is clear, according to observers, is that Prabowo’s presidency remains one that is for now unpredictable.