It took a move to China to discover her “Indonesian-ness”, said author Grace Tioso, who grew up in the authoritarian era of Indonesian President Suharto, when Chinese language and culture were suppressed for three decades.

Discriminatory practices against her ethnic group, such as being endlessly asked to prove her nationality by government offices and an unofficial bar from entry to state universities, left Tioso ambivalent about Indonesia, where she was born.

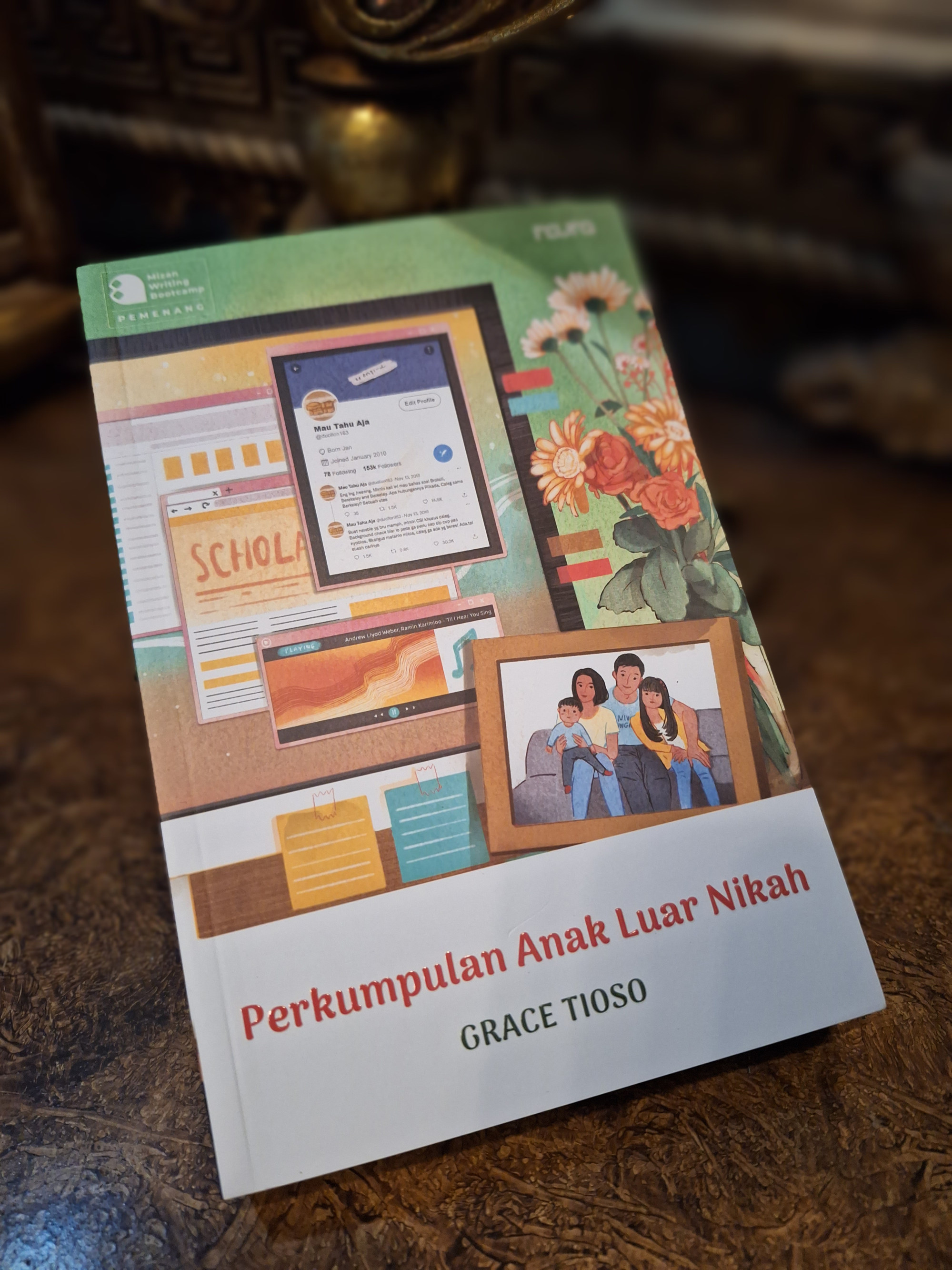

“I was eager to reconnect with my roots, so I went to university in China studying Mandarin,” said Tioso, the author of new book Perkumpulan Anak Luar Nikah (The Society of Out-of-Wedlock Children).

“But I didn’t feel I belonged in China, either. Instead, being in the ancestral land reaffirmed I was Indonesian, first and foremost.”

Tioso, who now lives with her husband in Singapore, was among the Indonesian-Chinese who grew up under Suharto’s 32-year rule, which saw ethnic Chinese businessmen drive the economy at the same time as racial tensions were fanned by the official delineation of people of Chinese descent as non-native-Indonesians (non-pribumi).

Her book explores the experience of the thousands of “out-of-wedlock” children born in the 1970s and 1980s to Indonesian-Chinese couples where the husbands, though born and raised in Indonesia, were officially “stateless”.

These “stateless” men were unable to marry legally. When they did so and had children, the infants were denied paternal names. Instead, they would grow up with “out-of-wedlock” signed on their birth certificates.

Ana Yu, a 45-year-old Indonesian-Chinese who lives in the United States with her American husband, describes herself as an “out-of-wedlock” child. Raised in Madiun, a small town in East Java, she said she initially felt strange when she saw the term on her birth certificate.

“As far as I knew, my parents were married. But there were dozens of us in my hometown, so all of us stuck together,” Yu said.

A colonial-era law is why Chinese-Indonesians can’t own land in Yogyakarta

A colonial-era law is why Chinese-Indonesians can’t own land in Yogyakarta

Melissa Tan, a Jakarta resident, is another “out-of-wedlock” child. The 48-year-old said reading Tioso’s novel was a bittersweet experience. “I could see a lot of my own life experiences in it, but at the same time, it also made me relive some past trauma.”

Tan was a university student during the May 1998 riots in Jakarta, witnessing horrific scenes as mayhem broke out in response to the economic crisis and the Chinese diaspora were blamed for the inequality and corruption of the Suharto years. More than 1,000 Indonesian-Chinese were killed and entire districts were burned to the ground.

“One of the characters in the book says she loves Indonesia, her land of birth, though cautiously. That’s exactly me,” Tan said.

The legal discrimination against Indonesian-Chinese might be a thing of the past, she said, but Sinophobia still lingered.

“Loving my own country cautiously means I must prepare myself and my children for every eventuality,” she said.

Indonesia currently outlaws dual citizenship. But last year, the Indonesian parliament started deliberating on a bill which would allow members of the Indonesian diaspora to hold two nationalities.

“It makes sense to extend the dual citizenship option to our diaspora so that Indonesia can also benefit from their investment and expertise,” said Ahmad Jazuli, a researcher at the Ministry of Law.

Government statistics claim there are around 8 million Indonesians living and working abroad.

Team Indonesia

In many ways, Tioso observed, the sense of suspended belonging common to Indonesian-Chinese has prepared them well for a life outside their homeland. She claimed many Indonesian-Chinese professionals, like her husband, had chosen to work overseas for better pay as employment for their expertise in Indonesia was non-existent.

“Chindos (as Indonesian-Chinese are colloquially called) are often in a bind. If we stay home in Indonesia, there are always those who question our patriotism,” she said. “If we go overseas, the same is said of us.”

Like their forefathers who relocated to Indonesia from China, many in the current generation find themselves as migrant workers in foreign lands.

Tioso’s novel has revived debate on an increasingly distant vignette of Indonesia’s complex history, capturing the attention of celebrities, including the Indonesian-German actor and singer Cinta Laura Kiehl, and actress Sherina Munaf.

“Millennial or Gen Z Chindos may be unfamiliar with this chapter of history,” Tioso said. “Their parents may be out-of-wedlockers, but they may never have told their children out of shame.”

Award-winning filmmaker and producer Ginatri S. Noer was effusive in her praise of the book. “It’s been a while since I’ve come to love an Indonesian novel so much like this one,” she said.

“Grace never held back as she told the story of how complicated it was to be Chinese in Indonesia,” she wrote on Instagram, saying she devoured the book in one go.

Surabaya resident Nur Aini, 26, said she had been unaware there were Indonesian Chinese who were denied citizenship in the past, let alone children who had to deny their paternity.

“I saw Cinta Laura [Kiehl] pose with the novel on her Instagram story and became curious about what the book was all about,” she said.

After Suharto’s fall, restrictions and administrative discrimination against Indonesian Chinese were gradually relaxed by successive administrations.

“The whole rigmarole with stateless Chindos is mostly over now. But it’s important to talk about it lest we forget,” Tioso said.

Tan, an “out-of-wedlocker” from Jakarta, said her father-in-law’s citizenship papers were still being processed when his son – and her future husband – was born. To ensure the son would have Indonesian citizenship, the family decided Tan’s mother-in-law would enter into a pretend marriage with her husband’s younger brother, who was the only family member whose citizenship papers were in order.

Under the old Indonesian law, a child’s citizenship was inherited from the father.

“Applying for Indonesian citizenship for Chindos in those days required bribes and time. My father-in-law eventually became a citizen 20 years later,” Tan said.

Chinese-Indonesians in the Netherlands feel the pull of home

Chinese-Indonesians in the Netherlands feel the pull of home

Tan said she planned to send her children to study abroad so that they have the option of building their lives there, if need be.

“I want my kids to have the options I never had. Patriotism doesn’t always mean you have to live and work here,” she said.

Yu shared the sentiment. Despite being married to an American, she still holds an Indonesian passport.

“I will never relinquish my green [Indonesian] passport willingly,” she said.

Yu said she hoped the Indonesian government was sufficiently bold to pass the dual nationality bill. Whatever the outcome, her heart would always call Indonesia home.

“If Indonesia ever made it to the [Fifa] World Cup Finals and faced the US team, I’d be on Team Indonesia in a heartbeat.”