She also noted that the industry had bounced back strongly since the end of the pandemic, with some 60 million people having gone to the cinema since 2022.

Minister for Tourism and Creative Economy Sandiaga Uno told a public talk on March 29 that Indonesia’s film industry had made “great strides” in recent times and said that his ministry would do its utmost to ensure that it continued to do so.

“To those in the film industry, I urge them to strengthen our national cinema,” the minister said. “Indonesian films have the potential to become a powerful instrument to promote the country and project a positive image of Indonesia to the world.”

Sandiaga further highlighted the importance of using cinema to “shape national identity, enhance national pride and showcase Indonesia’s beauty and richness on the global stage so that other countries won’t look down on us”.

His counterpart at the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, Nadiem Makarim, in a written statement posted to his ministry’s website, cited the production of 20 government-funded short films – via a grant programme – throughout last year as evidence of government support for the industry

Nadiem said his ministry had helped 19 local films enter international competitions, claiming eight of them won awards.

Some Indonesian films did receive international recognition last year. The short film Basri & Salma in a Never-Ending Comedy, by director Khozy Rizal, competed for the Short Film Palme d’Or at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, while in the superhero genre, Sri Asih received a Next Wave Features award at the Fantastic Fest 2023 in Austin, Texas.

Market projections by Statista, a global data and business intelligence platform, predict revenue from Indonesian cinema will reach US$732 million this year, with annual growth of 6.15 per cent over the next four years. By comparison, revenue from China’s cinema market is slated to be around US$17 billion in 2024.

Film critic Diah Utami said Indonesian cinema currently “punches below its weight”, but had the potential to augment the Southeast Asian nation’s soft power on the global stage.

“In Asia, K-pop culture and its drama series are proof that cinematography and storytelling remain powerful in projecting a country’s soft power,” she said.

Soft power, a term first coined by US political scientist Joseph Nye in 1990, is defined as a country’s ability to influence others using non-coercive tools such as culture, values and foreign policies.

But Yogyakarta-based book publisher and cinema enthusiast Ribut Wahyudi contends that filmmaking should not just be about “bringing glory to one’s homeland”. This should only be a knock-on effect.

“Cinematography is essentially an art form and shouldn’t be overly restricted by norms and taboos to the extent it suffocates creativity and the freedom of expression,” he said, adding that filmmakers in neighbouring Malaysia had broken such taboos with films like Tiger Stripes and La Luna.

An award-winning film director, who asked to be identified only as Alex, agreed with this assessment, saying government agencies responsible for supporting emerging talent in the film industry often tried to “redact” and “impose restrictions” on government-funded projects.

“Filmmakers applying for government grants are often dismayed at finding stipulations for their projects, such as ones stating the film shouldn’t be seen as encouraging LGBTQ rights, or depicting violence and so on.”

In trying to censor projects, Alex said, the government might be doing Indonesia’s emerging filmmakers a disservice by stifling their creative freedom at an early stage in their careers.

However, he said government agencies were still “on the right track” by providing assistance through certain initiatives to help Indonesian filmmakers reach bigger international audiences.

Funding remained a perennial challenge within Indonesia’s film industry, Alex said, with independent filmmakers often having to seek funding overseas. Their more mainstream counterparts, meanwhile, usually survive by catering to narrower local cinematic tastes.

“Most Indonesian cinema-goers want one thing only: entertainment. They want to laugh or even be scared when they watch films,” he said.

Film critic Nanda Winar Sagita lamented that some Indonesian producers were “not daring enough to buck market tastes” and go beyond certain genres.

“Our producers may be underestimating Indonesian film buffs by thinking their tastes are simple,” he said.

Nanda said it was high time Indonesian film producers took a chance on making more “intellectually challenging” films, as there were “top-quality scripts which continue to languish in a pile somewhere at producers’ offices because they are thought to be commercially unviable”.

Rakhmad Hidayattulloh Permana, a film critic for Gacmovies, agreed that comedy and horror genres were unbeatable in terms of mass appeal with Indonesian cinema-goers. He cited the 2024 horror-comedy release Agak Laen (Somewhat Different), which was watched in cinemas some 8 million times, breaking the record for the most tickets ever sold for an Indonesian film.

Even so, the big producers in those genres, such as Imajinari Pictures, and filmmakers like Charles Gozali continue to hone their skills and quality with each new release, Rakhmad said.

“Gozali’s newest offer in the horror genre, Pemukiman Setan [Satanic Dwelling], is a good example of fine and thorough research into its subject matter,” he said.

Despite its lack of panache, Alex said Indonesia’s film industry was in good shape, pointing out that cinemas were still popular with Indonesians, who “relish the collective experience of watching films at the cinema”.

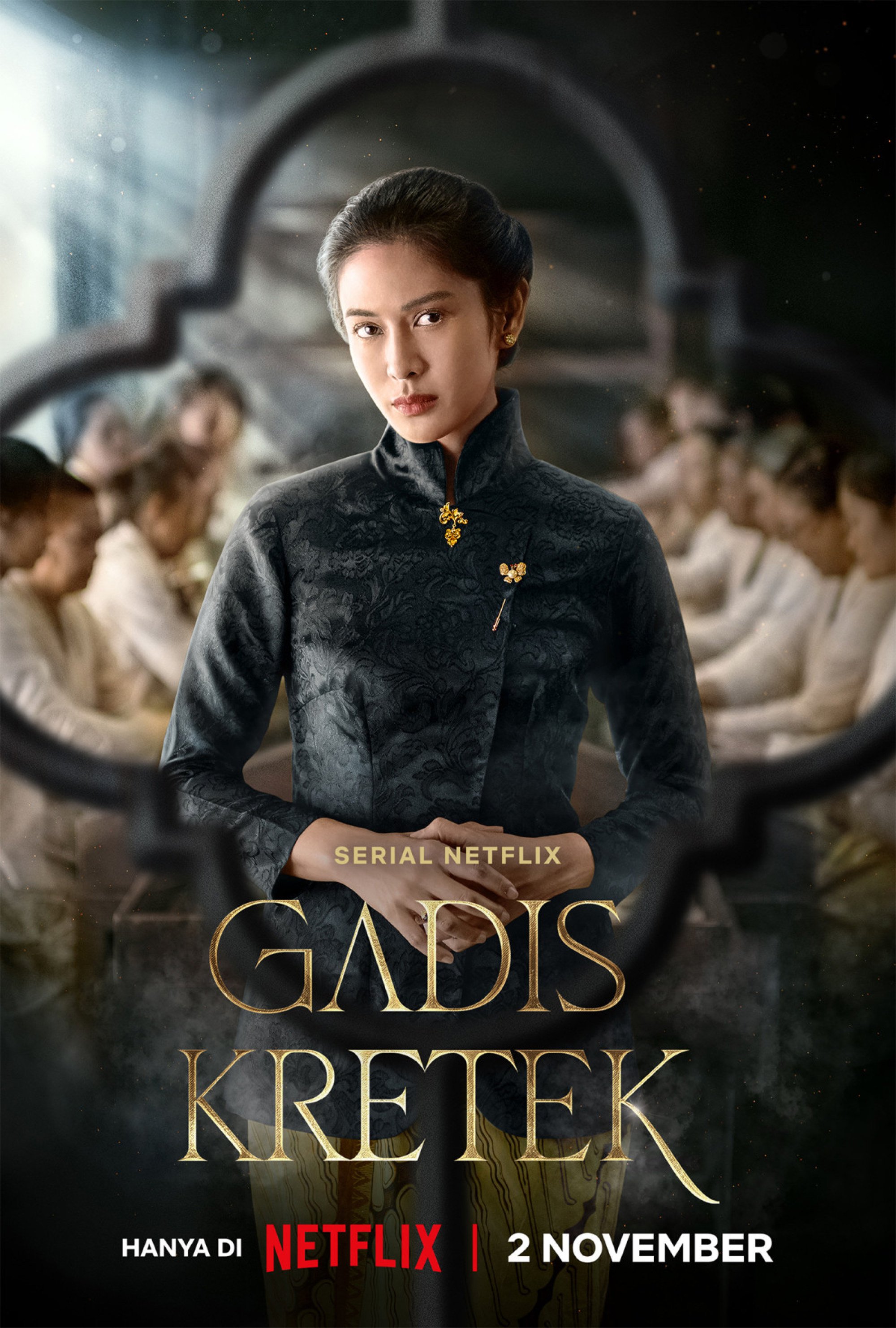

But he said so-called OTT streaming platforms such as Netflix were also making inroads into the country, and helping boost visibility of Indonesian productions, as subscription fees became increasingly affordable. The miniseries Gadis Kretek (The Cigarette Girl), released by Netflix in November 2023, reached the platform’s top 10 globally in its non-English shows category.

“OTT platforms are an important development. Gadis Kretek, for instance, would never have been made if it hadn’t been for Netflix,” Alex said.

Ribut agreed that Netflix’s foray into Indonesian cinema was a welcome development and listed highly successful films distributed by the company, such as Timo Tjahjanto’s The Night Comes for Us (2018) and The Big 4 (2022).

But ultimately, Nanda argued, both film producers and the government would have to take risks and support more nuanced types of projects in order to push the industry to new heights.

“Only groundbreaking films with diverse themes can achieve this.”