But for Chandrawati, these are just minor jabs, typical of the upper castes. They no longer define her sense of self or her aspirations for her children’s future. At least one of them, she dreams, will become a doctor.

“Back in the day, we couldn’t even show our face to Brahmins and Thakurs,” she said. “But after Mayawati’s government came to power, everything changed.”

Chandrawati, along with several others from her Dalit caste group in the village, stopped celebrating Diwali and Holi two years ago. For them, 14 April, BR Ambedkar’s birthday, is as important as 22 January, the day of the Ram Temple’s inauguration, is for others.

“We only believe in Babasaheb Ambedkar. We are followers of Jai Bhim not Jai Shri Ram,” she declared with a knowing smile.

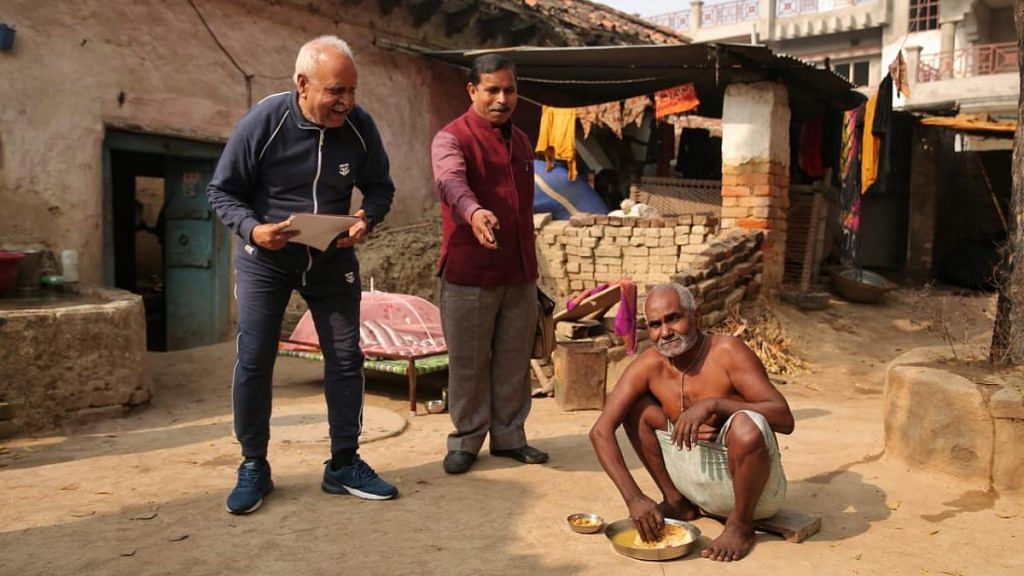

Less than 500 metres away from her house, Sukai Kannaujia, a Dalit from the Dhobi subcaste, rests on a wet charpoy for relief from the heat. Much like Chandrawati, he says things changed completely for Dalits after 2007 when Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) came to power with a majority in Uttar Pradesh.

“There was widespread oppression in the village before that,” he recalled. “We were never allowed to enter the temples. After BSP came to power, nobody could stop us.”

For both Chandrawati and Kannaujia, Mayawati becoming the chief minister marked a paradigm shift. For the first time, they experienced social and political samman (dignity) as Dalits. And it has persisted over the years.

However, the meanings of this dignity for Chandrawati and Kannaujia differ greatly.

For Chandrawati, it means rejecting Hindu temples where her entry was once prohibited. For Kannaujia, it means entering those temples freely. For Chandrawati, it’s about not calling Brahmin pandits for her children’s weddings, haunted by the humiliating memory of a priest chanting mantras from afar at her own wedding. For Kannaujia, it’s the pride of having a Brahmin pandit sit with his family for his son’s wedding. For Chandrawati, it’s the fearless freedom to not call herself Hindu. For Kannaujia, it’s the freedom to finally call himself Hindu with as much confidence as his former oppressors.

Yet, the BSP, which spurred these shifts, is now missing.

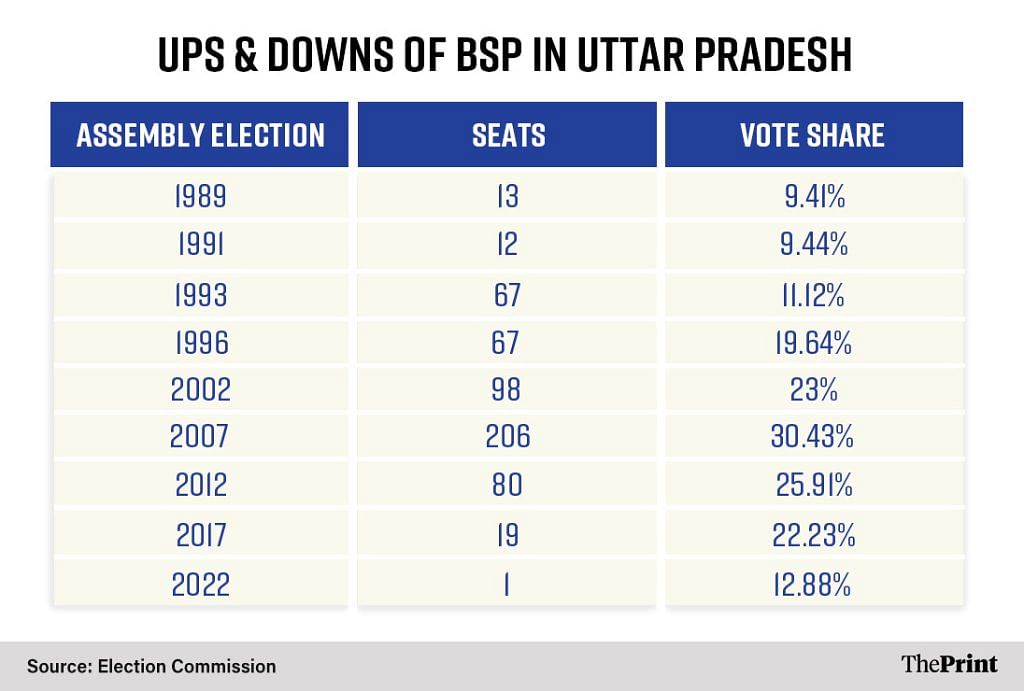

Forty years after its founding in 1984, the party that revolutionised Dalit politics in North India is almost invisible electorally and increasingly removed from the new sociocultural realities of Dalit identity and aspiration.

As Dalit politics finds itself torn between radical anti-religion Ambedkarism and a pro-Hindutva strand, the BSP seems to represent neither, leaving Dalit politics anchorless and more vulnerable to co-option than it has been in many decades.

As the BSP fights what many believe to be its penultimate battle for survival—its final test likely coming in the 2027 UP elections—several questions emerge.

With the political battle of the 1980s and 1990s between social justice and Hindutva seemingly won by the latter, what is the future of Dalit politics? And as the Dalit consciousness fostered by the BSP appears to have outlasted the party’s own fortunes, what are the prospects for the BSP under its leader, Mayawati? Both the BSP’s rise and fall hold some answers.

Also Read: Dalit housing, Ambedkar Gram to UPSC hubs. Are Mayawati’s legacies surviving in UP today?

Caste ‘annihilation’ to assertion

For ordinary Dalits like Chandrawati and Kannaujia, Mayawati provided their first taste of dignity. But for the Dalit intelligentsia, it was the maverick Punjabi scientist-turned-politician, Kanshi Ram, founder of the BSP and Mayawati’s mentor.

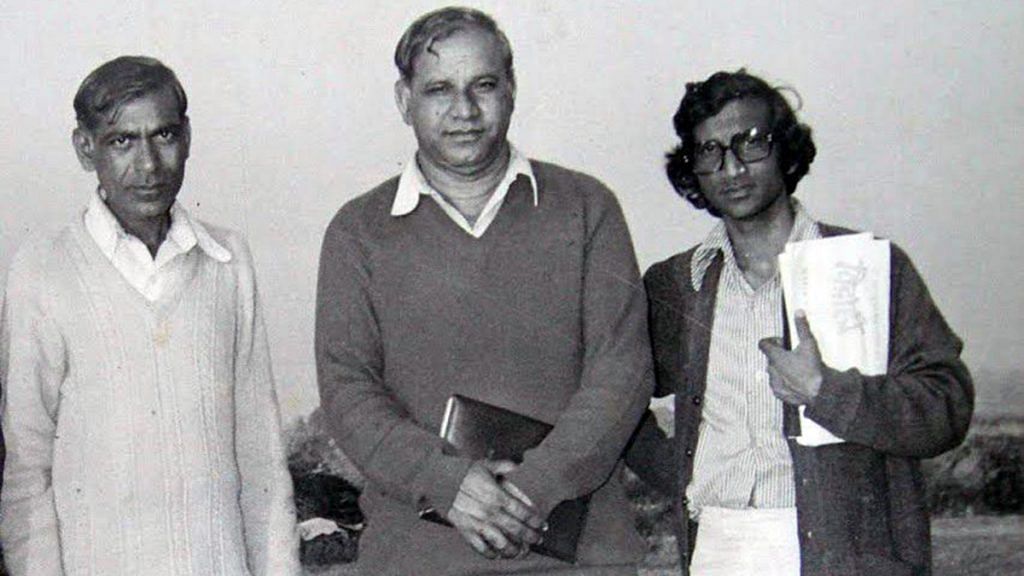

“If there is one leader in post-Independence India who understood Ambedkar, it was Kanshi Ram,” said Ravi Kant, associate professor of Hindi at Lucknow University. “Yet, he differed from Ambedkar foundationally. Kanshi Ram realised early on that caste wasn’t going anywhere, so instead of trying to annihilate it, he sought to mobilise it.”

In the 1970s and 80s, as the Congress’s political hegemony began to wane, Kanshi Ram appeared on the scene. He aspired for a political and social dignity for Dalits that was not only unimaginable, but also deeply offensive to the upper-caste vanguards of North Indian politics.

“Kanshi Ram knew that if society was mobilised at the social and cultural level, political dividends would automatically follow,” said Daddu Prasad, a former minister in the BSP government.

Prasad, who was expelled by the party in 2015 for “anti-party activities”, still identifies as the son of a bandhua mazdoor (bonded labour) and as one of Kanshi Ram’s proteges.

“He ran the Bahujan movement with a missionary spirit, relentlessly organising pad yatras, cycle yatras, music events, graffiti and wall writing,” recounted Prasad. “Even now I remember the impact his slogans—like Tilak, Taraju aur Talwar, inko maro joote chaar (The Brahmin, merchant, and warrior, strike them with four blows of a shoe)—had on the psyche of the people. He would say the unimaginable, and the unutterable, and we would feel ecstatic.”

Kanshi Ram’s initial task was to convince Dalits, backward classes, and minorities that they formed the majority of India’s population—the Bahujan samaj. The 1980s were a decade of democratic resurgence across UP as voting percentages rose up to 60 percent for the first time, primarily due to the participation of the lower castes and Dalits.

Dalits comprise 21.5 percent of UP’s population, according to the 2011 Census.

His slogans captured Kanshi Ram’s revolutionary politics. These included Jo zameen sarkari hai, woh zameen humari hai (Government land is our land); Mandal report lagu karo, warna kursi khali karo (Implement the Mandal report or vacate the seat); Brahmin, Thakur, Bania chor, Baki sab hain DS4 (Brahmins, Thakurs, Banias are thieves, the rest are DS4—a reference to the Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti, precursor to the BSP); and Jiski jitni sankhya bhari, uski utni hissedari (Greater the numbers, greater the share).

But it wasn’t just about sloganeering; Kanshi Ram’s strategy worked on multiple levels to mobilise different sections of Dalit society.

‘Exactly like the RSS’

Six years before founding the BSP in 1984, Kanshi Ram established the All India Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF), with a mission to “educate the educated”.

Essentially, BAMCEF was an organisation of Class 3 and 4 employees from communities that had benefited from reservation and Kanshi Ram used it to penetrate the larger Dalit and backward society, Kant explained.

“It was exactly like the RSS,” he said. “There were reading circles where people would sit, discuss history, religious texts, read Ambedkar. This is how cadres committed to the Ambedkar ideology were created.”

Fateh Bahadur, an IAS officer who worked closely with Mayawati, also draws parallels between RSS, the BJP’s ideological parent, and BAMCEF.

“The BSP was formed years after BAMCEF. And there was a time when BAMCEF would decide ticket distribution for the BSP—it was the moral, political, and ideological parent of the BSP in every way,” Bahadur said.

Much like the RSS, BAMCEF had different wings focusing on various facets of mobilisation. “According to me, the history wing was the most significant in terms of bringing a sense of history and identity to the Bahujan samaj,” said Kant.

For many in the Dalit intelligentsia, the ideological cadre-ization introduced by Kanshi Ram through BAMCEF in the 1970s and 80s has helped the BSP survive even today, despite what seems to be a self-imposed retreat from aggressive electoral politics.

Power at any cost

One of Kanshi Ram’s core strategies to build the Bahujan movement was to always be on the lookout for potential leaders, and, as Kant puts it, he created a “nursery” of them.

Several big names in UP’s politics today trace their political journeys back to Kanshi Ram—Sanjay Nishad of the NISHAD party, Om Prakash Rajbhar of the Suheldev Bharatiya Samaj Party (SBSP), Swami Prasad Maurya, who is now in the BJP, Babu Singh Kushwaha and Lalji Verma of the Samajwadi Party, Naseemuddin Siddiqui, now with the Congress, and the late Sone Lal Patel, founder of the Apna Dal.

“He was on a mission to create leaders,” said Bahadur. “He believed in a federal system that could last beyond himself.”

One such leader he discovered was Mayawati, who impressed him instantly.

“She once snatched the microphone away from Raj Narain on stage because he said something incorrect about Ambedkar,” Kant said. “Kanshi Ram was so impressed with her that he literally went looking for her and asked her to join the movement.”

At the time, Mayawati was preparing for the IAS exam, but Kanshi Ram painted a picture of an even more glowing future, Kant added: “He told her he would instead make her someone who would have dozens of IAS officers swarming around her.”

In 1984, Kanshi Ram formed the BSP with a clear mission—power at any cost.

Less than ten years after its formation, the BSP was indeed in power, albeit in alliance with the Samajwadi Party. On 14 December 1992—days after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya—Mulayam Singh Yadav and Kanshi Ram formed an alliance. For Kanshi Ram, it was a natural outcome of the Bahujan politics he had championed for years, marking the unprecedented coming together of OBCs, Dalits, and Muslims in UP.

For a while it seemed UP politics had decidedly defeated the politics of Hindutva, encapsulated in the slogan reverberating throughout the region—Mile Mulayam-Kanshi Ram, hawa mein ud gaye Jai Shri Ram (When Mulayam and Kanshi Ram come together, Jai Shri Ram blows away in the wind).

Except, two years later, Kanshi Ram withdrew from the SP-BSP alliance and joined hands with the BJP, which he continued to call Manuwadi and naagnath (snake).

And it was with the help of the BJP, a party that Kanshi Ram identified as Brahminical, that Mayawati, just 39, became the first Dalit chief minister of UP in 1995.

“Kanshi Ram was unapologetically opportunistic,” Prasad says. “He used to say, ‘Avsarwadi bano kyunki humein kabhi avsar mila hi nahi hai (Be an opportunist because we have never been given opportunities).’ He would take support from anyone to come to power, but never give them his support if he saw them as status-quoist.”

Indeed, in 1995 itself, Kanshi Ram outrightly rejected the possibility of campaigning for the BJP in the upcoming general elections. “The BSP stands for social transformation, while the BJP is a Brahminical party. We’ve come together for a short time to fight criminals,” he said in an interview with India Today.

Kanshi Ram’s gumption seared deep into the Dalit political psyche, argued Prasad.

“Here was a community that had been a bandhua mazdoor to bigger parties and upper-castes. Now, it had found the power to use and throw the upper castes,” he said. “It was a revolutionary act, and its after-effects still live on in the minds of the people.”

It was this politics of avsarvad that brought the BSP to power thrice in Uttar Pradesh with the BJP’s support—in 1995, 1997, and 2002. But these were tumultuous times, and for more than 20 years, no government in UP served a full term. Until 2007.

Also Read: ‘Heart has soured’—why UP’s RSS workers are lying low in BJP campaign

Historical rise & seeds of decline

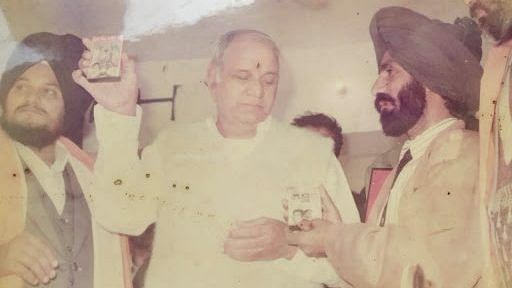

In 2007, a year after Kanshi Ram’s death, Mayawati came to power as chief minister for the fourth time. This time she needed no SP or BJP, winning a majority of 206 seats with 31 percent of the vote.

For mainstream media, it was nothing short of a miracle. She was termed the “newly armed liberator of the heartland”, “the sorceress of the mass mind”, “the highest diva of Dalit politics”. Almost overnight, she became the second most important woman in Indian politics, after Sonia Gandhi.

Mayawati achieved this through a kind of social engineering previously championed only by the Congress, though perhaps more by accident than by design. Unlike Kanshi Ram, she included upper castes in her electoral equation, giving Brahmins 86 of the 403 seats the BSP contested.

“By wooing upper castes, particularly the Brahmins from the BJP camp, Mayawati has shown her political acumen as a master strategist, better than the combined powers of the BJP’s think-tank, the Samajwadi Party’s money, and muscle power and the Grand Old Party’s GenNext,” an India Today cover story declared.

But this victory carried the seeds of decline. For the ideologically trained cadres of BAMCEF and the BSP, the party’s overtures to Brahmins spelled an existential crisis.

“It was the beginning of the Brahminisation of the BSP. Suddenly, the BSP worker did not know who their fight was against,” said KK Gautam, a former minister in the BSP government who left the party in 2015. “BSP was a party that had come to power after an ideologically driven, radical movement. Now, it wanted to be in power at the cost of the principles of the movement that rode it to power.”

There were key differences in the opportunism and ideological flexibility of Kanshi Ram and Mayawati, according to Kant.

“Kanshi Ram knew he was using the upper-caste parties for some strategic reason,” Kant said. “Mayawati, on the other hand, misconstrued these strategic alliances for actual social solidarities. She didn’t realise they were there only for power.”

This ideological shift was evident in the change of the party’s slogans. Kanshi Ram’s radical slogans gave way to Brahmin-embracing ones, such as

“Brahmin shank bajayega, haathi dilli jayega“— The Brahmin will blow the conch, the elephant (BSP’s symbol) will go to Delhi.

Around this time, Mayawati also stopped the cadre-isation through BAMCEF, hollowing the party out from within. “BAMCEF produced workers with a missionary zeal. Without them, BSP was bound to be like any other party,” said Gautam.

Moreover, as Mayawati’s hold over the party grew, she began purging the organisation of the “nursery of leaders” Kanshi Ram had cultivated.

“One by one, leaders who had joined the BSP from various caste groups—Dalits, OBCs, and Muslims—under Kanshi Ram began to leave the party,” Gautam claimed.

The mass purging of the BSP has consequences even today. Of the Lok Sabha candidates the SP has announced in this election, at least 14 are BSP defectors. “There could be a book on the leaders who were forced to leave the BSP,” said Bahadur.

Dalit politics began to show cracks, too. Allegations surfaced that the government favoured the Jatavs/Chamars, who constitute over 50 percent of the Dalit population in the state, over other subgroups.

What started as a social consolidation of the entire Bahujan samaj by Kanshi Ram, therefore, slowly became a consolidation of the Dalit samaj, and then finally, just the Jatav samaj under Mayawati, Kant argued.

Yet, Mayawati’s ambitions kept growing. By 2008, she was declared by the media as the third pillar of Indian politics—alongside Sonia Gandhi and LK Advani.

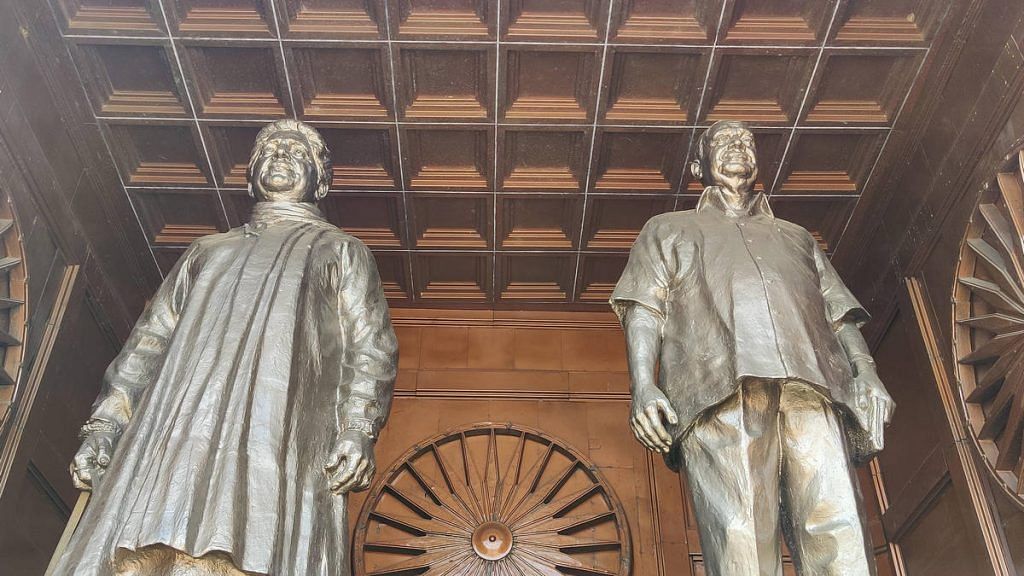

“If I am fit to rule the largest state of India, why can’t I run the whole country?” she would say. She built massive monuments to herself, drawing heavily from the state coffers.

But the party was rotting from within.

“Allegations of corruption were becoming louder, and people on the ground were getting increasingly disillusioned,” says Gautam. “But she created an ecosystem around her where nobody could tell her this. If you spoke the truth, you could get fired from the party.”

“Before the 2012 election, I told her as unequivocally as possible, ‘Behenji sarkar nahi ban rahi (we won’t be forming government)’.”

Creating ‘friendly subalterns’

In his book, The Buddha and His Dhamma, Ambedkar describes his chagrin at his father’s insistence that all his children read the Ramayana and Mahabharata.

Ambedkar’s wrote that his father believed these epics would help them overcome their “inferiority complex” as “untouchables”. He’d cite characters like Drona and Karna, “small men” who achieved greatness, as examples. “‘Look at Valmiki,’ his father would say, ‘he was a Koli, but he became the author of [the] Ramayana.’”

Back then, as now, Dalits have grappled with asserting dignity through two conflicting aspirations—gaining access to dominant Hindu culture or completely rejecting it.

In the 19th century, when the idea of a united Hindu nation gained steam, a big question emerged—how to include the ‘lower’ castes? This became a central theme for mobilising a political Hindu identity.

A major part of this project was distancing Hinduism from casteism.

Ram Mohan Roy, who started the Brahmo Samaj, argued that the practice of untouchability wasn’t part of Hinduism originally. Dayananda Saraswati, founder of the Arya Samaj, proclaimed that the ancient Hindu system assigned varnas based on skills, not birth. Later, Later, VD Savarkar was more direct about the problem he saw with the caste system—it made Hindus weak compared to the more organised and aggressive Muslims.

The RSS inherited this centuries-old desire to strengthen and unify the Hindu community by eclipsing caste identities.

In the 1980s, as the Ramjanmabhoomi movement gained traction and Kanshi Ram mobilised a Bahujan identity, the RSS intensified efforts to create an all-encompassing Hindu identity— creating in the process what political analyst Sajjan Kumar calls the “friendly subalterns”.

And while the mobilisation of the Bahujan identity stopped under Mayawati, that of the Hindu identity kept growing.

“The RSS sees no difference among castes,” said Indra Bahadur Singh, an RSS vistarak from Mau village in Mohanlalganj. “You see our shakhas, everyone comes and bows to the same flag.”

To combat its Brahminical image, the Sangh uses community meals as one of its tool for outreach.

“The most central way in which untouchability is practiced is by not eating with lower castes,” Singh explained. “For the last many decades, we have organised khichdi bhoj, where everyone brings khichdi from home, mixes it, and eats together—there can be no stronger repudiation of the allegation that we are casteist.”

Additionally, the RSS organises events like wrestling matches and tells “stories” about caste unity—typically involving a Muslim villain.

“For instance, we tell the story of how during the Mughal rule, there was once a Gadaria herder (a Dalit caste) herding his cattle, who, when he saw a Hindu princess on a palanquin being attacked by Muslims, gave up his life to save her,” Singh said animatedly. “This way they realise that we all have always been one.”

For decades, the RSS has co-opted Dalit icons, built temples for them, and rewritten complex histories to fit narratives of a united Hindu struggle against Muslim oppression, Kant argued.

He cited Suheldev, a 17th-century king, as an example. “Nobody has ever seen his photograph, but the Hindu nationalists modelled him on the popular image of Maharana Pratap, and now that is his popular depiction,” Kant said.

While the Chamar-Jatav Dalits have not been easy to sway, the process of Hinduising sub-castes like the Valmikis, Dhobhis, Sonekars, and even Pasis has largely succeeded.

“It is only the Chamars who see themselves as outside of the Hindu community,” said RSS’ Singh. “They keep saying Jai Bhim instead of Jai Shri Ram. The educated among them go to the cities, come back and misguide them.”

In contrast, Singh argued, the Valmikis in his village are the “cleanest”, “most educated”, and “closest to dharma”. “They even built a grand Durga temple in the village that everyone goes to.”

Basara village’s Sukai Kannaujia, who belongs to the Dhobi caste, agrees.

“Being a Hindu gives us a sense of identity,” he said. “When Muslims call themselves Muslims, why can’t we do so? We are Dalit, but repeating that incessantly is backward, not forward politics.”

Also Read: What happens to an ‘adopted’ village when a ‘parent’ MP moves on? The story of Mayawati and Mall

Post-BSP Dalit politics

Dalit politics in Uttar Pradesh is at a turning point, where the BJP is poised, at least for some, to fill the vacuum left by the BSP.

“The violence against Dalits is often blamed on dominant caste groups in the villages today, and not necessarily on the BJP. So, the shift to the BJP is tactical — a sort of protection from Samajwadi Party-emboldened OBCs who are hostile to the rise of Dalits — and ideological,” write Sudha Pai and Sajjan Kumar in their book Maya, Modi, Azad.

It is an observation that gets easily corroborated on the ground, where Jai Shri Ram and Jai Bhim coexist for many Dalits, sometimes without a sense of contradiction.

While Dalits across villages view upper castes as antagonistic, the BJP and the RSS are not seen as their representatives, even among the sections of Jatavs/Chamars who follow Ambedkar. The BJP has managed to shed its Savarna party image by culturally and ideologically assimilating Dalits and giving subcastes neglected by the BSP positions of leadership within the party and government.

“There are Dalit MPs and ministers in this government, so how can the BJP be considered an anti-Dalit party?” asked Rachit, a Jatav youth from Mohanlalganj.

For him, the BJP is a party of the sarvajan samaj, even if the community’s vote still goes to the BSP.

“Our vote goes to the haathi (elephant) we say Jai Bhim, but we have no problem in saying Jai Shri Ram also,” he said. “We will vote for the BJP if needed. Now, we are not wedded to any political party. We got dignity from the BSP, but we have to look after our interests post-BSP too,” he says.

While several Dalits remain hopeful for Mayawati’s electoral resurrection, her absence on the ground has created a glaring void.

“Dalit politics is at a crossroads right now. Activists are mobilising the BSP’s legacy base through Ambedkarism, while the BJP-RSS is mobilising the rest,” said Gautam. “The BSP needs to not only fight more but also reimagine its fight—can the 1980s politics of social justice suffice now?”

As Pai and Kumar argue in their book, the desire for material advancement among Dalits and an increased inclination towards Hindutva make it unlikely. They contend that the Dalit movement in UP has entered a post-BSP phase, noting that this is not necessarily a bad thing. To the authors, it indicates confidence within the community to make their own social, political, and electoral choices, moving towards different parties as needed.

Nevertheless, despite the BSP’s decline, Dalit mobilisation on the ground remains strong, as seen with the rise of parties such as the Bhim Army.

However, the BJP-RSS seem confident about co-opting this Ambedkarite assertion too.

“We don’t see Jai Bhim as a problem,” said a Lucknow pracharak, who goes only by the name Virendra ji. “Ambedkar was a kattar Hindu. He was anti-Muslim, anti-Pakistan. It is okay if there are attempts to convert to Buddhism, too. Buddha was, after all, an avatar of Vishnu… Jai Bhim and Jai Shri Ram can coexist.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)