Its tasting menu, which starts at £120 (US$150), tracks a journey across West Africa, including jollof rice, the region’s signature dish.

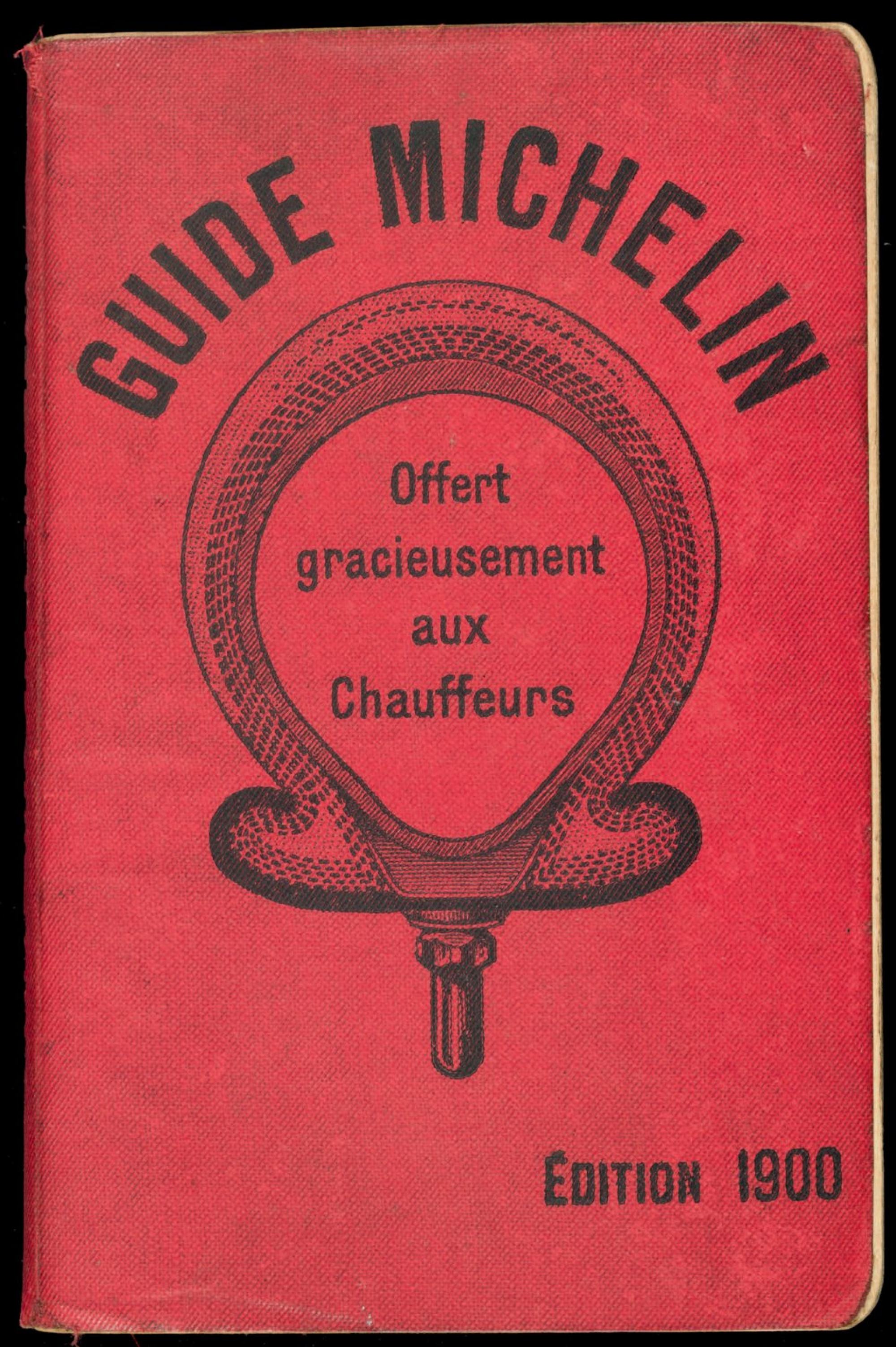

The first Michelin Guide was published in 1900 and provided French motorists with such information as maps, and listings of service stations and hotels. The goal was to encourage road travel and drive demand for the company’s core product: tyres.

In 1926, the guides began awarding a star to dining establishments; five years later, ratings expanded to the three-star system still in use. While stars are technically awarded to restaurants, the achievement is often attributed to their head chefs.

The judging process is secret. Anonymous reviewers visit restaurants several times before awarding stars.

When I was growing up in the industry as a young chef, restaurants like this weren’t around

Michelin maintains that assessments are based on five criteria: quality of products; mastery of cooking technique; harmony and balance of flavours; voice and personality of chef as expressed in the cuisine; and consistency between visits and throughout the menu.

In Brazil, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo have a combined 13 restaurants with at least one star. None count black head chefs – in the country with the highest population with African descent outside Africa itself.

Michelin publishes no guides for the Caribbean and Africa.

According to the group’s chief inspector in North America, nearly 200 cuisine types are represented in the global selection – yet no restaurant whose menu focuses on West African foods has received a star.

In Paris, Sacko’s single-star MoSuke uses a good amount of West African ingredients, but the menu is international.

It was a pretty toxic environment. I was not being treated with the respect I deserve.

The Michelin website lists more than 16,000 restaurants, including ones “recommended” by Michelin – places deemed notable but not worthy of a star.

Just 13 are listed under the Africa category; only one, Piment in Hamburg, has a star, and its menu is focused on North African cuisine.

Adeyemi notes that African gastronomy has gained global recognition in recent years.

“When I was growing up in the industry as a young chef, restaurants like this weren’t around,” he says of Akoko. “So I was forced to have to learn the modern British culture, the modern Asian culture, the modern French culture.”

But even with this expanded selection, Michelin still carries a strong association with fine dining, a term that remains charged with prestige and exclusivity.

Meanwhile, many chefs of colour face continuing obstacles navigating the culinary industry – one of them being racism in the kitchen.

James Cochran, for one, cut his teeth working in a string of Michelin-star kitchens until 2018, when he opened 12:51, his own restaurant in London.

Cochran says running his own kitchen has allowed him to highlight his West Indian and Scottish heritage. He has worked in hospitality since his teens in Kent, but after moving to London, Cochran found a dark side in the sector.

While he was accustomed to being the only person of black or mixed heritage at work, he was not expecting to deal with high levels of racial abuse from colleagues.

“It was a pretty toxic environment,” he reflects. “I was not being treated with the respect I deserve.”

Black chefs face business challenges, too, according to Adejoké Bakare, head chef at Chishuru in London.

Many black restaurateurs are told they are not “commercial enough”, she says, noting a list of prerequisites that landlords put forth and investors present before they feel comfortable putting money into black-led businesses.

Even prior experience at distinguished restaurants guarantees nothing, says Asma Khan, the Indian-born British chef-owner of Darjeeling Express, who faced discrimination securing a space for her restaurant.

Chishuru was opened by Bakare in 2020, and was named best restaurant of 2022 by London’s Time Out magazine.

The £48 set menu featured dishes such as tamarind-glazed fried tripe and her take on gbegiri, a West African soup with seared chicken and spicy bean and lentil purée.

This autumn, the Nigerian-born Bakare will reopen her restaurant in a new location after closing the previous one in October 2022.

She summarises the hesitation she noted among landlords in the city centre as, effectively: “We don’t think you are the look of people in this area.”

This stands in contrast to another skin-colour-focused kitchen story that recently garnered attention.

British chef Thomas Straker went viral after posting a photo of his all-white, all-male team of cooks for the coming outpost of his eponymous restaurant.

Straker responded to the backlash by asking commenters to “gather CVs of any chefs you think we’re missing from the team” before he issued an apology.

Part of the wider problem for black chefs are the financial barriers to becoming one.

“Representation at the upper levels of gastronomy starts with access to a culinary education, financial support, mentorship and mobility, which are challenges to aspiring chefs,” wrote the Michelin Guide’s chief inspector in North America in an email.

To complete an associate’s degree at the Culinary Institute of America, one of the world’s foremost cooking schools, a student in New York would have to pay US$35,520 for tuition alone.

Matters of exclusion extend to dining out. The average cost of a tasting menu at a three-star restaurant in the UK is £240, excluding wine – a price that is out of reach for most people.

“The Michelin star doesn’t mean what it used to,” Cochran says. “It’s kind of a dated accolade.”

Michelin could use its expansion to help tackle its lack of diversity. Later this year, it will publish an inaugural guide for Atlanta in the US, presenting it with fresh opportunities to find black dining spots that merit stars; the city’s population includes 48 per cent black residents, and traditional African-American cooking is integral to Atlanta’s food scene.

Even with the obstacles, Adeyemi hopes more young black people will note his own success to envision a career in hospitality as a viable path.

Fretting that black chefs are conditioned to view certain foods as inferior, Bakare insists that cooks of colour maintain their sense of identity while persevering to prove the value of their work.

“Rightly or wrongly, we put ourselves in that category without other people doing it for us,” she says.

Most importantly, the industry needs to recognise that the market for food from black chefs from all over the world exists and is growing fast.

Bakare is baffled by the perception that diners do not want West African food. She heard over again from landlords in central London: “People in this area might not come to eat that food”, to which Bakare responds: it is something “which time and time again, we have debunked”.