Jamaal recalled that in 1991, then PM Chandra Shekhar brought UP Chief Minister Mulayam Singh Yadav to Ballia in the hope of kicking off development work. But instead of welcoming him, the upper castes waved black flags and threw chappals, angry at his pro-reservation stance during the Mandal era. After Yadav angrily left the dais, Chandra Shekhar urged the people they’d have to “learn to behave”.

Over thirty years later, some things haven’t changed in this largely rural, flood-prone region. Development is still lagging and, according to Jamaal, everyone thinks they are a revolutionary.

“Ballia me har ghar me neta hai, isliye vikaas nahi ho paya (There is a leader in every house, which is why development is stalled),” he joked.

Villagers complain that despite the “PM constituency” tag, Ballia remains “backward” and that none of its representatives, whether from the Samajwadi Party or BJP, have brought much development over the years.

Despite some positive changes like a double-line railway, new trains, and improved roads, Ballia still grapples with pending projects like a medical college—a promise oft-repeated in election speeches—and a university that remains vulnerable to flooding.

“Ballia is surrounded by the Ghaghara and Ganga rivers on three sides,” said Vishal Yadav, a 23-year-old Parmandapur resident who is preparing for the Staff Selection Commission (SSC) examination. “When these rivers flood, the university too gets waterlogged. In 2019, the DM and SP had to use a boat to reach the university premises. Classes for most courses still don’t run on campus, and the university mostly facilitates education via affiliated colleges.”

As the constituency gears up to vote on 1 June, hopes for the future remain muted.

This election, the BJP candidate is Chandra Shekhar’s younger son Neeraj Shekhar, who is pitted against the Samajwadi Party’s Sanatan Pandey. But residents are sceptical.

For one, this isn’t the junior Shekhar’s first bid for Ballia. He entered politics with the Samajwadi Party, winning the bypoll from the Lok Sabha constituency after his father’s death in 2007. He was re-elected in 2009 but lost to BJP’s Bharat Singh in 2014 during the Modi wave. In 2019, BJP’s Virendra Singh Mast took the seat.

Now, Neeraj is relying on both his father’s legacy and Modi’s clout, but old-timers point out a contradiction.

“Till the time Chandra Shekharji was alive, the lotus could not bloom in Ballia. He opposed the BJP’s politics his entire life,” said Jamaal. “It is ironic that his son is fighting from the BJP but you can’t expect him to be another Chandra Shekhar. That kind of politics is finished now.”

Neeraj Shekhar, however, told ThePrint that the country comes first for the BJP, just as it did for his father.

“The BJP has worked for the benefit of the country,” he said. “Most of the party’s policies are based on socialist ideology.”

Also Read: Remembering Chandra Shekhar, India’s 8th PM who was in office for just seven months

Politics, ‘vested interests’, stalled projects

When it comes to Ballia’s crumbling infrastructure, locals blame the failings of their politicians. But many, especially the elders, still credit eight-time MP Chandra Shekhar for building a school, hospital, and the constituency’s only rail over-bridge.

Centenarian Changur Singh fondly recalled how Chandra Shekhar’s election symbol would change with almost every poll he contested and still he would manage to win.

“When he would have to fight an election, he would spread a gamcha and seek donations from the villagers. He would meet people from all sections and everyone would donate to him, whatever little they could,” he said. “Politicians of today don’t have the calibre to do that kind of politics now. Now, it’s all about money.”

Some villagers remember the “idealist socialist leader” Chandra Shekhar as the glue that held the Janata Party together during his presidency from 1977 to 1988. Their accounts echo the vivid description in author Attar Chand’s 1991 biography, The Long March, where he writes Chandra Shekhar was “forced to accept the role of a wet nurse to three warring leaders in the Janata Party, Morarji Desai, Charan Singh and Jagjivan Ram”.

In those tumultuous times, Chandra Shekhar’s drive to improve local facilities was personal, according to his nephew Naveen Singh.

“In his younger days, he once suffered a boil on his thigh and failed to get good treatment. Realising that there was no good medical facility in his area, he wanted to construct a hospital,” he said.

However, this project in Ibrahimpatti, located in Salempur Lok Sabha constituency, took many years to get off the ground, added Singh, who is the president of a trust that operates the Devasthaly Vidyapeeth school established by Chandra Shekhar’s brother Kripashankar Singh in 1988.

“The hospital came up in the 1980s, but unfortunately, couldn’t be functional for years due to lack of funds, resources, and doctors’ reluctance to serve in the area,” he explained. “The Jannayak Chandrashekhar Hospital and Cancer Institute has now been handed over to a private foundation running other hospitals in neighbouring Ghazipur. It started functioning last year.

According to Ballia resident Ramavtar Singh, the fundamental problem was that VIP constituencies have a problem of diye tale andhera” (darkness below the lamp)— a situation where resources and opportunities don’t translate to progress and development. But he doesn’t blame Chandra Shekhar.

“Chandra Shekhar ji was a national leader. He was admired across India, especially in states like Bihar, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, etc. He would himself say that he has to think about the entire country and not Ballia alone,” Ramavtar added.

Another issue that Ballia residents point to is that development projects often face hurdles due to vested interests and local political interference.

“Traffic would remain stalled within the Ballia city for hours, but whenever road widening projects were proposed, people would get them stalled by contacting local politicians. Nobody would part with a portion of personal land. There is only one flyover in Ballia which connects the TD College with the district hospital. Yahan har insaan ek neta ko jaanta hai (Every person here knows one politician),” said Jamal.

Currently, two ministers in Yogi Adityanath’s council belong from this region—Transport Minister Dayashankar Singh and MoS Danish Azad Ansari (the latter’s village is in Salempur Lok Sabha). In the previous Yogi cabinet too, two ministers, Upendra Tiwari and Anand Swarup Shukla, were from Ballia.

Throughout Ballia, residents express their disappointment with local politicians.

“Leaders should be asked why the region remained without development. They beautified only their own houses,” alleged Tarachand Prasad Gond of Agarsanda village. “The only medical facility here is the district hospital where you can get first aid and preliminary treatment, but for all major ailments and accidents, patients are referred to hospitals in Mau and Varanasi.”

In Piyariya village, 23-year-old Adesh Kushwaha, another SSC aspirant, is upset about the lack of a library and higher educational institutions. “I have to travel over 20 kilometres to access the library in the city. There is no development here,” he said.

Socialist legacy, development gap

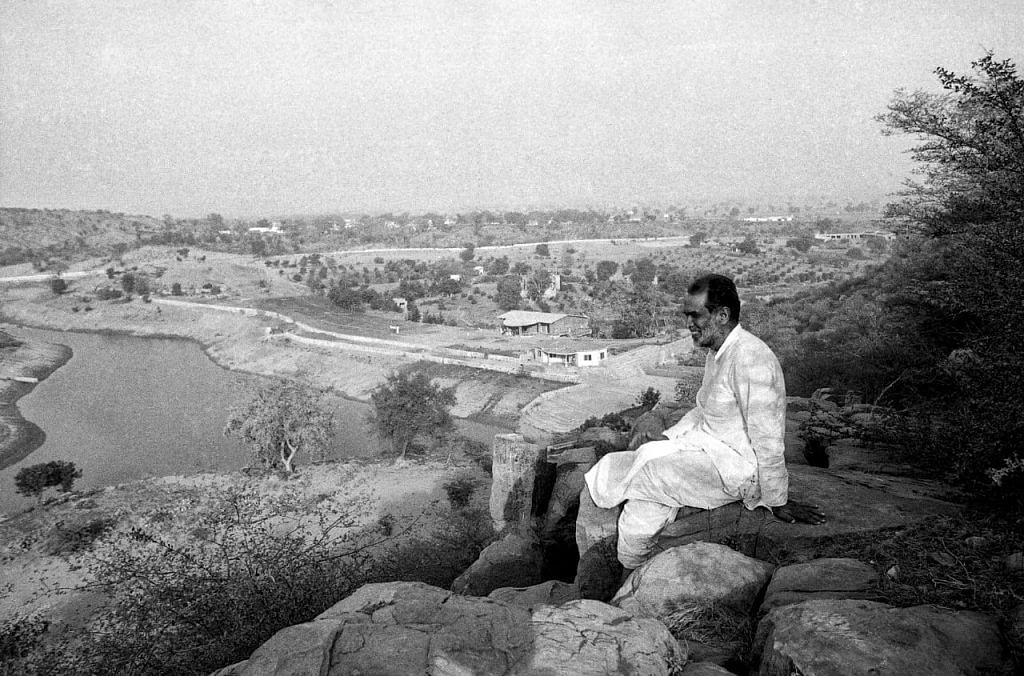

No other corner of Ballia has received as much political attention as Korrha Nobarar village in Sitab Diara area of Ballia’s Bairia — the birthplace of socialist icon and anti-Emergency crusader Jayaprakash Narayan, often referred to simply as JP.

This village, spread across four acres at the confluence of the Ghaghara and Ganga rivers, shares a border with Lala ka Tola village in Bihar’s Saran district —another contender for JP’s legacy.

Here, a curious story has unfolded of socialist monument-building coupled with shortfalls in development.

The most famous part of Sitab Diara is Jai Prakash Nagar, a complex of structures dedicated to JP Narayan, established by Chandra Shekhar and beautified by various central governments. Painted in a palette of red, mustard, and pink pastels, these buildings include the Jai Prakash Memorial, Prabhavati Library, a postgraduate girls’ college, a Khadi centre, and a primary health centre.

While the Jai Prakash Nagar memorial was developed in 1986, the first pucca road linking Narayan’s birthplace with the rest of Ballia came up in 1982.

“I vividly remember those times. We would carry cement, wood, and sand on camelback and travel to Sitab Diara for hours,” recalled Jai Prakash Singh, the former PM’s nephew who still lives in Chandra Shekhar’s birthplace in Ibrahimpatti. “Chacha ji (Chandra Shekhar) personally oversaw the memorial’s construction.”

According to Singh, political heavyweights from Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Sushma Swaraj to Mulayam Singh Yadav and Nitish Kumar would visit to pay their respects during the ‘JP Jayanti’ celebrations spearheaded by Chandra Shekhar between 2001 and 2003.

But for some years now, a tussle has been brewing over whether the “cradle” of socialism is in UP or Bihar.

Nitish Kumar kicking off the Bihar Vikas Yatra from neighbouring Lala Tola village in February 2010 and his government’s subsequent development of a JP Museum was seen by many in Ballia as an affront to their claim as JP’s birthplace.

Then, in 2015, ahead of the Bihar state polls, the Modi government also announced a national museum in Lala Ka Tola, attracting criticism from Narayan’s family and former UP minister Ambika Chaudhary, who alleged that “confusion” was being created by terming Lala Ka Tola as the birthplace” of Narayan. Yet, in October 2022, Union home minister Amit Shah unveiled JP’s statue in Lala Ka Tola on the latter’s birth anniversary.

Notably, Chandra Shekhar’s son Neeraj, who joined the BJP in 2019, has also emphasised that there are misconceptions about Narayan’s birthplace and that it was Sitab Diara of UP’s Ballia, not Bihar.

But this contest over legacy is not the only cause of resentment in Sitab Diara.

In 2015, some residents launched a fast unto death, demanding that Sitab Diara be merged with Bihar. They were upset, villagers say, because of the apathy of the UP government toward the area, which was troubled by annual flooding and land erosion, rendering thousands of villagers homeless every year.

It was only last year that this issue was addressed with a ring embankment to protect the area from floods. However, about 100 families in the Bhagwan Tola area at the bank of the Ganga remain outside the embankment and expect floods to wreak havoc again this year.

“We boycotted the 2022 Uttar Pradesh assembly election because we have to shift to the embankment area and relocate every time Ganga gets flooded,” said 40-year-old Brij Kumar Yadav, a resident of Bhagwan Tola. “We have made a temporary embankment like previous years, but the same thing will repeat this time too. We are all landless and don’t have money to construct a pucca house like the upper castes in the village.”

Yet, even those villagers who own pucca houses in nearby villages say that life near the confluence of the Ganga and Ghaghara is difficult and painful.

“There is only one hospital nearby, in Jai Prakash Nagar. They give good service, but even to deliver a baby, patients are referred to hospitals in Chhapra, which is much closer than Ballia,” said Anjani Singh, a resident of Bawan Tola.

Another issue, he added, was the lack of institutes of higher education in the region. “As of now, most move out to Lucknow, Patna, Chhapra, Allahabad for higher studies,” he noted.

On the development gap in this hub of socialist history, Jai Prakash Singh said that Chandra Shekhar’s illness and subsequent death in 2007 resulted in the area getting neglected.

It was only about two years ago that villagers heaved a sigh of relief when the ‘BST bandh vali road’—the only road connecting Jai Prakash Nagar to the Chanddiar police chowki—was repaired.

‘No mafia could raise their head’

Chandra Shekhar was known more for his oratory, idealism, and national appeal than for developmental projects in the area, acknowledge many of his admirers in Ballia. They hint, however, that his powerful voice and clout were enough for them.

“(Chandra Shekhar) considered Ballia his home but felt that if one’s neighbour is fine, then one too is fine. His style of politics was different. There wasn’t an orator like him. When he would speak in Parliament, everyone would listen,” said Parmandapur resident Gunja Singh. “The BJP could never emerge here till the time he was alive.”

Residents also claim that Chandra Shekhar’s presence kept the local mafia in check, but now things are different. They point to the suicide of gun shop owner Nandlal Gupta as a case in point. Gupta had accused local moneylenders of harassment on Facebook Live before taking his own life in January of last year.

His wife had named 18 people, including moneylenders, for allegedly torturing her husband and forcefully getting his residential plot registered in their name despite having cleared all dues. Ballia police subsequently arrested a dozen persons in connection with the case.

“Until Chandra Shekhar was alive, no mafia could raise their head but now, several mafias from the dominant upper castes have gained sway here,” said another Ballia resident Atmaram.

He gave the example of gangster Kaushal Chaubey, who was arrested by the Uttarakhand police in 2019 after being on the run for 15 years. According to Atmaram, Chaubey still has influence in the area.

Villagers also talk about Chandra Shekhar’s grandson, BJP MLC Ravi Shankar Singh ‘Pappu’, who had a murder case lodged against him in connection with the killing of Ballia resident Sanjay Singh in May 1996. Pappu was acquitted of the charges by a local court in November 2022 for lack of evidence.

Jamaal, however, said that Chandra Shekhar’s sons enjoy a clean image.

Legacy vs caste

To ostensibly capitalise on the continuing affection for the former PM in Ballia, the BJP dropped sitting MP Virendra Singh Mast in favour of Neeraj Shekhar this election. The Samajwadi Party has fielded Sanatan Pandey, called ‘Baba’ by villagers, who lost in 2019 by a slim margin of some 15,000 votes.

But residents are weary and disgruntled this poll season, with anti-incumbency sentiments running high as the BJP has held the Ballia seat for a decade.

Election after election, politicians mention the Ballia medical college as a poll promise, but the facility is yet to develop. While a university named after Chandra Shekhar was built during the Akhilesh Yadav government, it needs an upgrade.

Neeraj Shekhar, however, told ThePrint that these issues would be addressed.

“The pending project of a medical college got delayed because of lack of land availability. The foundation will be laid after the election,” he said.

In Ballia’s Piyariya village, residents acknowledge that Neeraj has the advantage of his father’s legacy, but that might not be enough this time as the youth are particularly disgruntled with the “failure of the Agnipath scheme,” unemployment, inflation, lack of an advanced medical facility, and BJP’s “jumlebaazi” (empty promises).

“I had been preparing for entry into the Army for two years but dropped the idea when the Agneepath scheme was launched. I am now preparing for the SSC examination. The BJP promised one crore jobs but where are they?” rued Kuldeep Kushwaha, 26.

Another resident, Hariom Verma,20, said that unemployment is the biggest concern of the youth.

“Against 26,000 vacancies in paramilitary forces, about 20 lakh applied… this means that the rest of the youth will stay at home,” he scoffed.

Some residents also claim that while Neeraj has a strong legacy, he lacks visibility in the region. “He comes, meets his supporters only, and leaves. The SP is in a better position this time,” said 35-year-old Shyam Narayan Yadav.

Expecting the Muslims and Yadavs to rally behind it anyway, the SP has fielded a Brahmin candidate from Ballia.

According to the local BJP unit, in Ballia Lok Sabha constituency, both Brahmins and Scheduled Caste voters constitute about 15 percent each of the electorate, followed by 13 percent Rajputs, 12 percent Yadavs, 8 percent Bhumihars, and 8 percent Muslims.

Anil Pandey, a resident of Piyariya village and the principal of a homeopathic college in Bihar’s Siwan, claimed the SP candidate is getting the “sympathy” of the Brahmin community.

“He was attacked by rivals in the previous election and the general feeling is that he was wrongfully defeated. Sixty percent of Brahmins will vote for him. The community is divided,” he said.

But the family legacy and the fact that the BSP has fielded a Yadav candidate may help Neeraj Shekhar, coupled with the fact that Suheldev Bharatiya Samaj Party (SBSP) chief OP Rajbhar is now with the BJP.

“Last time, the SBSP had fielded a candidate in this Lok Sabha constituency, taking away over 65,000 votes. But this time, Rajbhar is with BJP, which may help the party. More than anything, the fact that BSP has fielded a candidate here might take away some of the Yadav vote,” Pandey speculated. “Last time, SP-BSP were in a coalition. This time, that advantage is missing.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: ‘Raja Bhaiya’ factor tilting odds against BJP-led NDA in Kaushambi, Pratapgarh & now Mirzapur