Sega Retro

Most of the changes on the Sega Retro wiki every day are tiny things, like single-line tweaks to game details or image swaps. Early Monday morning, the site got something else: A 47MB, 272-page PDF full of confidential emails, notes, and other documents from inside a company with a rich history, a strong new competitor, and deep questions about what to do next.

The document offers glimpses, windows, and sometimes pure numbers that explain how Sega went from a company that broke Nintendo’s near-monopoly in the early 1990s to giving up on consoles entirely after the Dreamcast. Enthusiasts and historians can see the costs, margins, and sales of every Sega system sold in America by 1997 in detailed business plan spreadsheets. Sega’s Wikipedia page will likely be overhauled with the information contained in inter-departmental emails, like the one where CEO Tom Kalinske assures staff (and perhaps himself) that “we are killing Sony” in Japan in March 1996.

“Wish I could get our staff, sales people, retailers, analysts, media, etc. to see and understand what’s happening in Japan. They would then understand why we will win here in the US eventually,” Kalinske wrote. By September 1996, this would not be the case, and Kalinske would tender his resignation.

Not all of the compilation is quite so direct or relevant. There are E3 floor plans, nitpicks about marketing campaigns, and the occasional incongruity. There is a Post-It note stuck to the front of the “Brand Strategy” folder—”Screw Technology, what is bootleg 96/97″—that I will be thinking about for days.

Sega Retro

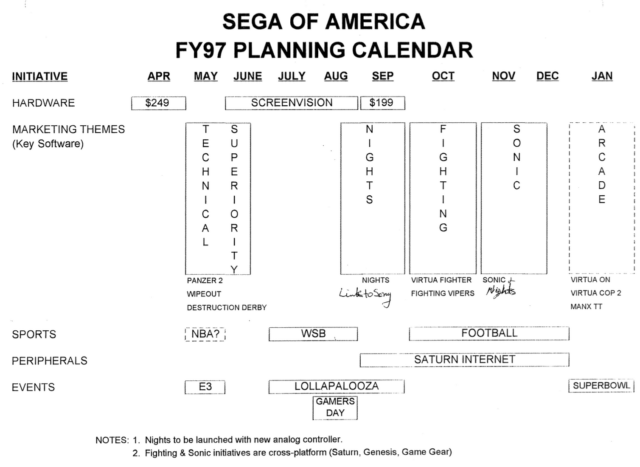

If you were a Sega fan or just have a clear memory of Sega’s irreverent (OK, “edgy”) console marketing style, you can see scanned storyboards for two of Sega’s ads from its “Nothing Else Matters” campaign for the Saturn: “La Zona Blanca” and “Armageddon.” And you can read Kalinske’s notes to marketing head Neil Cohen demanding 50 percent of the ad be game footage and asking, “When did we decide on Hare Krishna cult members?” Later on, you can see Lollapalooza as a key, multi-month milestone in Sega’s marketing plan for fiscal year 1997. It was a different time.

“La Zona Blanca,” a 1996 Sega Saturn advertisement that thoroughly assures you that it dates back to 1996.

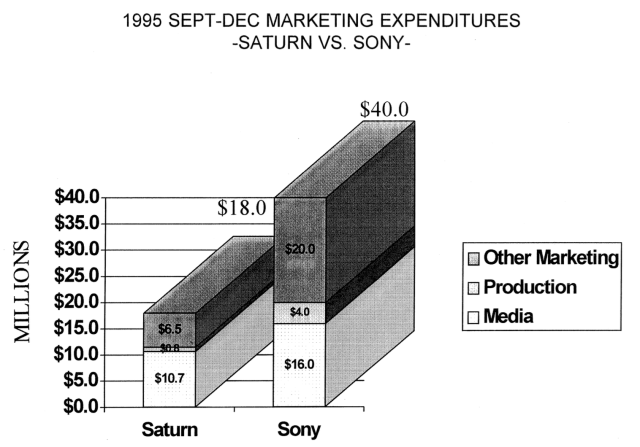

Crucially, there is nearly as much Sony as there is Sega in this brand analysis. Before the Nintendo 64 showed up, Sega spent a lot of time watching Sony and figuring out how it could keep the company from gaining a foothold. Strategies included “position Saturn as the technically superior next generation system,” “leverage exclusive Saturn peripherals,” and “strengthen sports line-up and ship titles concurrent with season.”

Sega Retro

Hindsight suggests none of those really worked and that Sega’s other primary obsession, lowering hardware costs after its launch, both for competition and margins, backfired. The retail margin on a core $250 Saturn system, without pack-in games, was 6 percent, or $15, while Sony seemed to be offering 10 percent core, 15 percent pack-in.

“How Did Sony Do it?” one slide rhetorically asks. The answer, according to Sega, is that it was perceived to be cheaper, its software “looks better than ours,” that Sega “equity has been damaged by 32x and Sega CD,” and that Sony has “effectively leveraged their considerable equity from consumer electronics.” All Sega had to do, according to the next slide, was improve its software, get pricing advantage, improve its advertising, spend better on TV advertising, and “dramatically improve” its game timing. Simple enough.

The posting on Sega Retro may not last forever, though the PDF has likely entered many interested hands by now. Reading through it feels like getting early access to the research folder of an unwritten follow-up to Console Wars.

For another perspective on the troubled Saturn, be sure to read Senior Technology Editor Lee Hutchinson’s memoir of his time at retail outlet Babbage’s, where the Saturn surprise-launched early for $400 in 1994 and, as he recalls, “rotted on our shelves.”