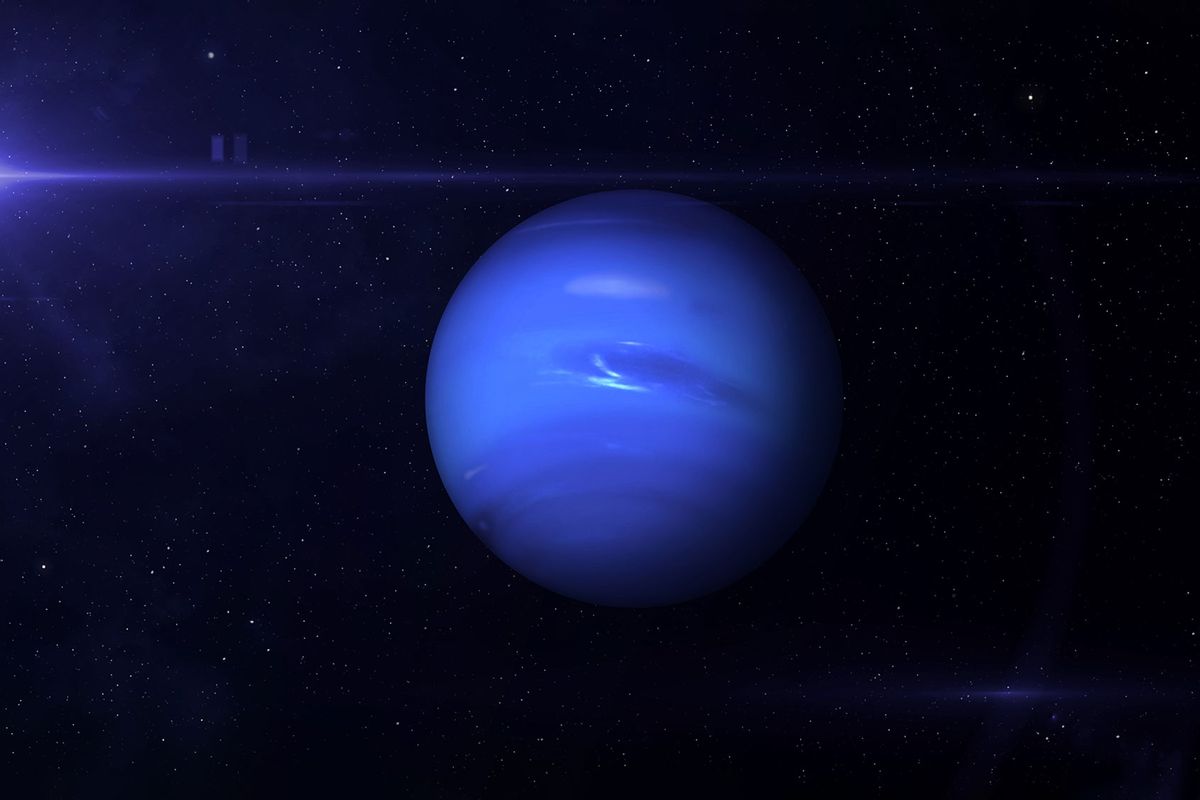

The ice-giant Neptune, the most distant and third largest planet in our solar system, is a distinctive dark blue ball of gas, which may appear calm but is actually throttled by a chaotic atmosphere. It’s actually the windiest place in our solar system. Despite earning the label “ice-giant” in part because of its massive size (and also because it is primarily composed of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium), Neptune is far enough away from Earth that our astronomers continue making new discoveries of this enigmatic world.

For example, researchers from colleges like the University of California, Berkeley, Stanford University and the University of Leicester believe they have finally cracked a mystery that has bedeviled astronomers since 2019: The enigma of Neptune’s vanishing clouds.

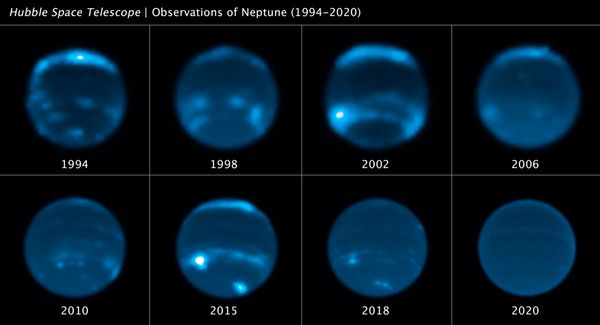

The culprit, the authors hypothesize in a recent paper in the journal Icarus, is the ultraviolet rays that the Sun emits throughout the solar system. They drew from archives of near-infrared observations of the eighth planet from both the Keck and Lick Observatories and the Hubble Space Telescope between 1994 and 2022, documenting how cloud activity evolved during that time. They establish a positive correlation between cloud activity and the amount of electromagnetic energy emitted by the Sun at a very specific wavelength, which is known as Solar Lyman-Alpha irradiance.

“The clear positive correlation we find between cloud activity and Solar Lyman-Alpha (121.56 nm) irradiance lends support to the theory that the periodicity in Neptune’s cloud activity results from photochemical cloud/haze production triggered by Solar ultraviolet emissions,” the authors concluded.

This sequence of Hubble Space Telescope images chronicles the waxing and waning of the amount of cloud cover on Neptune. (NASA, ESA, Erandi Chavez (UC Berkeley), Imke de Pater (UC Berkeley))

This sequence of Hubble Space Telescope images chronicles the waxing and waning of the amount of cloud cover on Neptune. (NASA, ESA, Erandi Chavez (UC Berkeley), Imke de Pater (UC Berkeley))

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“I was surprised by how quickly clouds disappeared on Neptune.”

“Even now, four years later, the most recent images we took this past June still show the clouds haven’t returned to their former levels,” Erandi Chavez, the study’s first author and a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a NASA statement. “This is extremely exciting and unexpected, especially since Neptune’s previous period of low cloud activity was not nearly as dramatic and prolonged.”

The study’s most prominent author elaborated on the significance of that low cloud activity.

“These remarkable data give us the strongest evidence yet that Neptune’s cloud cover correlates with the Sun’s cycle,” Imke de Pater, emeritus professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley and senior author of the study, said in an additional NASA statement. “Our findings support the theory that the Sun’s UV rays, when strong enough, may be triggering a photochemical reaction that produces Neptune’s clouds.”

“I was surprised by how quickly clouds disappeared on Neptune,” de Pater added. “We essentially saw cloud activity drop within a few months.” Right now, it’s not clear when or if they’ll return.

This is not the only recent big news to come for fans of the frigid behemoth. The European Southern Observatory recently used their Very Large Telescope (VLT) to observe a dark spot on Neptune, the first time that has ever been done with an Earth-bound instrument. Patrick Irwin, Professor at the University of Oxford in the UK and lead investigator of the study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, explained in a statement that “I’m absolutely thrilled to have been able to not only make the first detection of a dark spot from the ground, but also record for the very first time a reflection spectrum of such a feature.”

The dark spot is likely he result of mixing hazes and ices. Next to the dark spot was a smaller, brighter spot that is actually a previously unknown cloud species.

“In the process we discovered a rare deep bright cloud type that had never been identified before, even from space,” study co-author Michael Wong, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, said. Clearly, there is more to learn about Neptune, but a mission may not arrive there until 2049.