ESO/M. Kornmesser

The Pew Research Center published the results of a new public survey on Thursday, the 54th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing on the Moon. The survey assessed Americans’ attitudes toward space exploration and space policy issues.

Similarly to five years ago, the survey found that Americans broadly support the national space agency, NASA. Three-quarters of respondents had a favorable opinion of NASA, compared to just 9 percent with an unfavorable opinion.

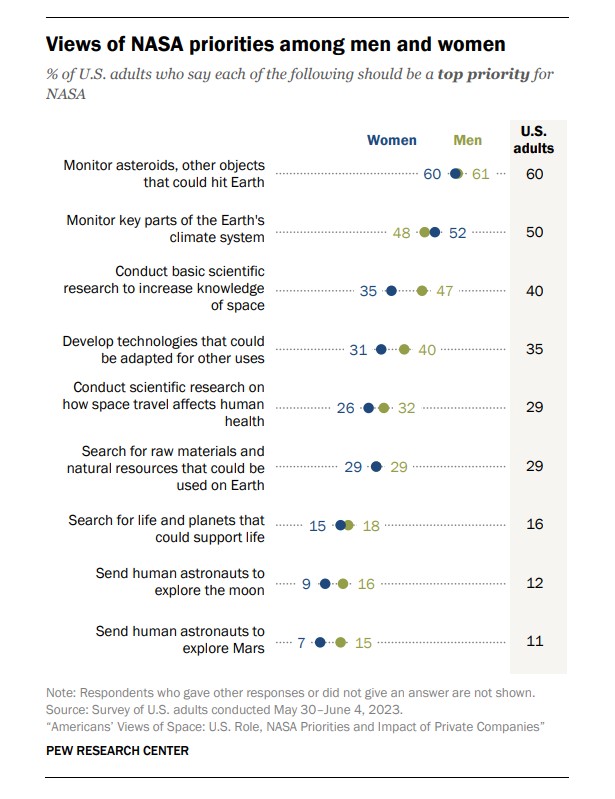

However, as several previous surveys have found, the public has far different priorities for NASA than are expressed in the space agency’s budget. In this new report, based on a large survey of 10,329 US adults, the highest support came for “monitor asteroids, other objects that could hit the Earth” (60 percent) and “monitor key parts of the Earth’s climate system” (50 percent). Sending astronauts to the Moon (12 percent) and Mars (11 percent) lagged far behind as top priorities for respondents.

Additionally, support for deep space exploration by humans was especially low among women. Just 9 percent of female respondents listed sending humans to the Moon as a “top priority” for NASA, and 7 percent of women said the same about sending humans to Mars.

The percentage of men and women who say the following areas should be a ‘top priority’ for NASA.

Pew Research Center

These priorities come in stark contrast to the funds NASA actually spends on exploration. In fiscal year 2024, for example, NASA has asked Congress for $210 million to continue the development of the Near-Earth Object Surveyor mission. Planned for a launch in 2028, this planetary defense mission will detect, track, and characterize impact hazards from asteroids and comets. NASA also proposes to spend about $2.5 million on Earth Science missions.

Meanwhile, the space agency has asked for about $8 billion to fund its ongoing Artemis program missions next year, including rockets, spacecraft, and landers, to allow for a human landing on the Moon later this decade. NASA officials say the Artemis program will allow the agency to learn skills and techniques that will eventually allow astronauts to fly to Mars in the 2030s or 2040s.

Protect the planet

Despite this disparity, NASA has stepped up its planetary-defense activities. Less than a decade ago, the space agency spent less than $50 million a year on detecting and tracking potentially hazardous asteroids, issuing notices and warnings of possible impacts and taking the lead in coordinating planning and response across US government agencies.

The agency, in concert with the European Space Agency, took a notable step forward in November 2021 with the launch of the Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission, which intercepted a near-Earth asteroid and then impacted a small asteroid in 2022. This demonstrated the capability of NASA to potentially deflect an incoming asteroid if a threatening object is found.

Overall, these survey results reinforce the notion that while public support for NASA is fairly broad, it does not run that deep, particularly for human space exploration. And where NASA spends the majority of its funding is where the public—in surveys, at least—seems to be least interested. So what does this mean for space policy?

For a long time after the Apollo program, NASA and space policy leaders lived in hope of seeing another era of support for a large space-exploration budget. In the 1960s, NASA’s budget peaked at about 5 percent of federal spending. Now it is about 0.5 percent. If NASA’s budget would just double or triple, space enthusiasts would say, think of all the wondrous things we could accomplish.

But those days are never coming back. The US public likes having NASA and astronauts and seeing cool things happen in space. But by and large, their priorities are much more Earth-bound. As Phil Larson, a key space policy official at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, told me a few years ago, “The vast majority of the public thinks that we should have a space program that saves Earth.”

To NASA’s credit, the space agency finally seems to have acknowledged this. Instead of shooting for the Moon with a much larger budget, it has nurtured a commercial space industry. Through public-private partnerships on lunar landers, spacesuits, and other activities, NASA is beginning to fit its deep-space exploration plans within the current budget it receives from the federal government. It has also prioritized landing the “first woman on the Moon” the next time humans go there. Perhaps that will win broader support for lunar exploration in future surveys.