Points of connection and intersectionality between his Macau, that of the metropolitan Portuguese settler/expatriates, and that of the Chinese population, are recurrent themes.

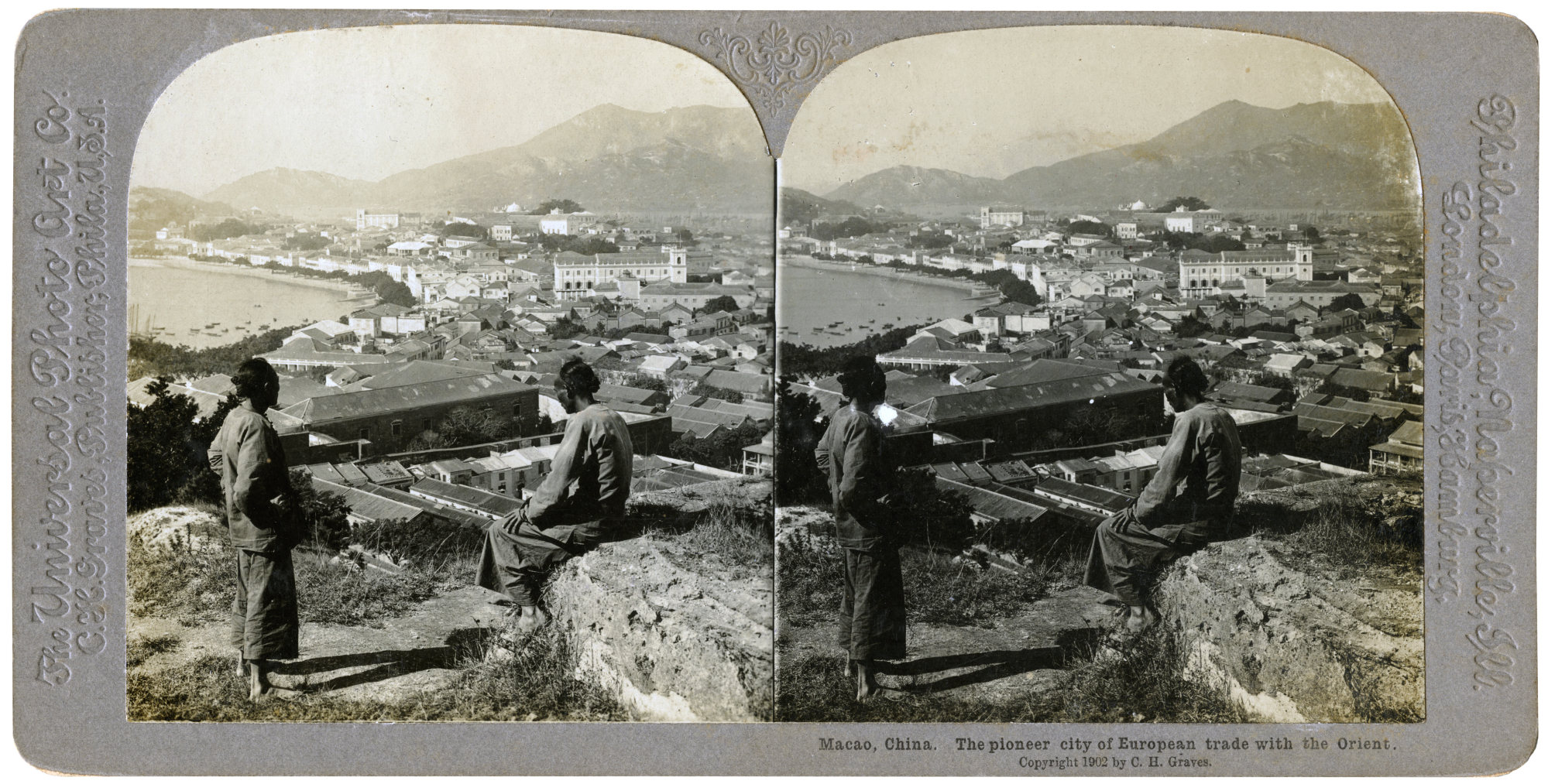

The Praia Grande, with its timeworn vista of junks and the odyssey of its heroic, adventurous lorcha crews, inspired my early writing

An extended post-war sojourn in Portugal, where he studied law at Coimbra, caused him to discover that his own personal ancestral homeland – the ultimate source of all his creativity – was in fact Macau, not Portugal.

The relatively small, still picturesque town was recalled with saudades (“lingering, somewhat regretful nostalgia”) and portrayed as inhabited by a more liberal, tolerant and racially inclusive colonial bourgeoisie than may actually have been the case at the time.

In a foreword to Nam Van – Tales of Macao (2020), a posthumously published English translation of a Portuguese-language collection first published in 1996, Senna Fernandes noted the hypnotic effect of Macau on his own writing.

“Nam Van is the Chinese name for the Praia Grande. The long sandy beach of olden times, with its graceful curve, was transformed over the centuries into an elegant thoroughfare, the nerve centre of the administrative and social life of Macau, and the most sought-after residential area.

“The Praia Grande, with its timeworn vista of junks and the odyssey of its heroic, adventurous lorcha crews, inspired my early writing and my first dreams as an author.

“The Praia Grande nurtured the basis of my sensitivity and imagination, with the nostalgic tone of its dusks and the sadness of its winter mists.”

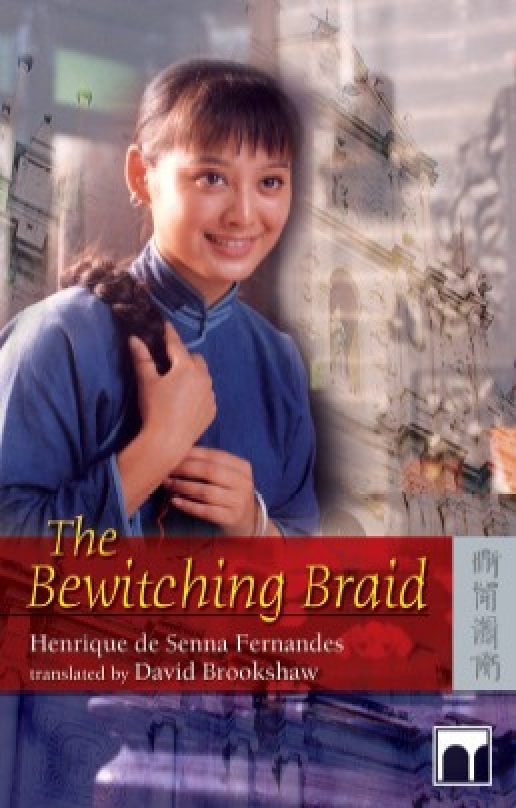

The Bewitching Braid (2004), his charming novel of a beautiful water-seller nicknamed “Ah Leng”, illuminates the hard lives experienced in a city that – well into Senna Fernandes’ young adulthood – was still largely without a reliable town water supply.

Otherwise comfortably off residents in various areas, such as his own substantial family home below Guia Hill, ordinarily bought water for domestic use, by the bucketful, from ambulant women vendors.

In this and other stories, he writes movingly about the lives and struggles of mui tsai (“little sister”), the girls sold by poverty-stricken parents into virtual slavery; a common feature of the time in which he grew up. Macanese families also had mui tsai, but most preferred to depict them as servant girls.

How Macau was observed from Hong Kong’s vantage point has been widely explored in local literature. Less well documented are how certain aspects of Hong Kong society were observed from Macau, and by the Macanese themselves. How the Hong Kong Portuguese chose to live – as distinct from their Macau-resident cousins – was closely observed.

An old girlfriend of the narrator, encountered in later years, “had become the perfect Englishwoman, with a diction that never ceased to surprise him”.

And of the Macanese woman’s British husband, “he was the complete Anglo-Saxon, tall and well-built. He had a determined mouth, and the arrogant look of someone used to getting his way. What a contrast with Candy’s dark, Oriental Portuguese face!”

Various cultural compromises and ventriloquisms deliberately made by some community members, to better fit with British colonial life, are acutely and sympathetically observed.