Four years ago, when Daniel Patrick Garrett was prescribed buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, in 2019, he drove to 10 pharmacies before he found one that filled his prescription.

One told him his ID wasn’t clear enough for them to confirm his identity, another wanted to put him on a pain management contract and a third pharmacy didn’t accept the discount card he needed to use in order to afford the medication, Garrett said. The pharmacy he finally found to fill the prescription was a 100-mile round trip from his home in Jackson, Tennessee. Once Garrett and his partner separated the next year and he lost access to a car, getting to the clinic became even more challenging.

That’s when Garrett went to his first detox program, through which he was able to get the cost of his medication covered. In Garrett’s first round of medication-assisted treatment or MAT in 2019, he was so stressed by the process of obtaining the medication that he wasn’t really seeing its effects. Once the financial and physical barriers were removed in his treatment program, things got a lot better, he said.

“The main issue surrounding MAT access is not the drug itself,” Garrett told Salon in a phone interview. “It’s the systems in which they are prescribed, dispensed and provided.”

“The main issue surrounding MAT access is not the drug itself. It’s the systems in which they are prescribed, dispensed and provided.”

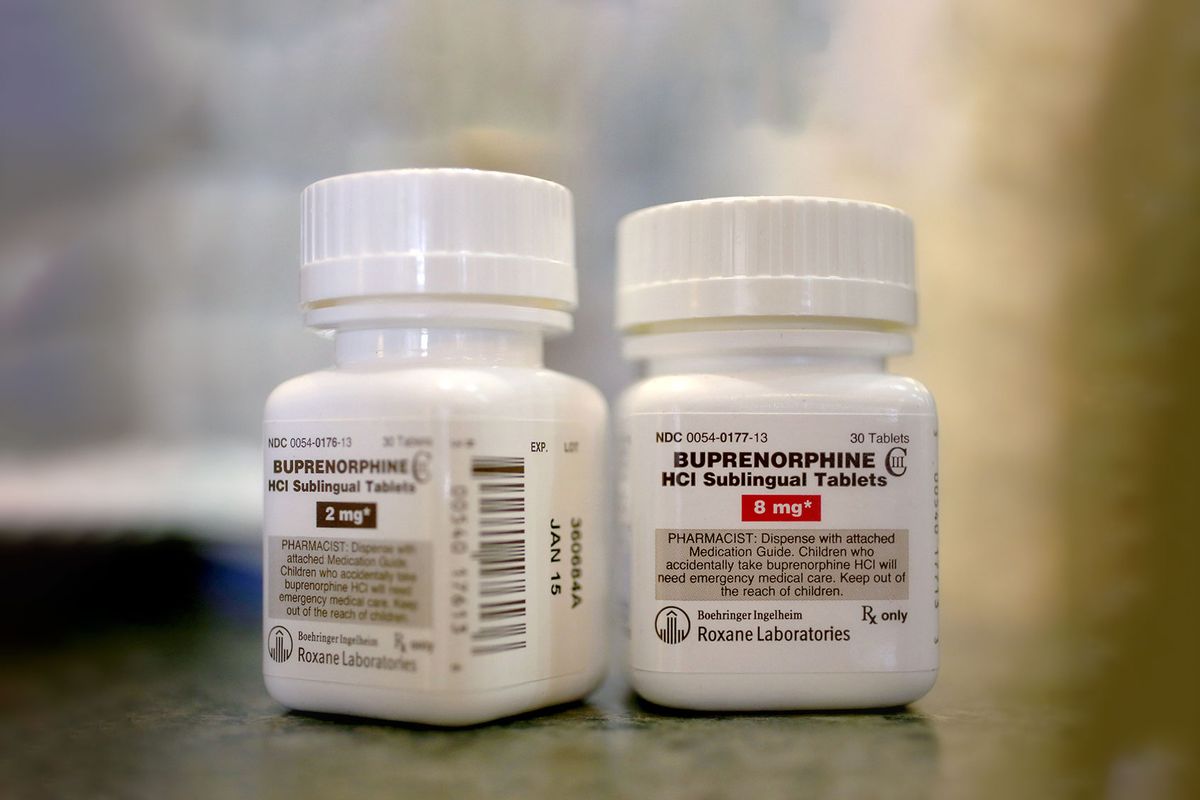

Patients with substance use disorder and their providers have to jump through various hoops to access MAT, which includes buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone. All of these drugs are opioids, but are markedly different in how they function compared to heroin and morphine. In December 2022, President Biden signed the Mainstreaming MAT Act of 2023, removing one barrier to treatment by no longer requiring so-called “X-waivers,” which doctors were previously required to fill out to authorize the outpatient use of buprenorphine.

But the bill was quietly passed at the end of the year, many doctors are still hesitant to prescribe these medicines and access hasn’t improved as much as some had hoped.

“I am happy that it’s gone,” said Dr. Ryan Marino, an emergency medicine physician at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, referring to the X-waiver. “I am still skeptical that this will expand accessibility and access.”

More than 46 million people in the U.S. met the criteria for substance use disorder in 2021, but 94% of them went untreated. Nationwide, over half of rural counties do not have a buprenorphine provider and roughly one-third of Americans living in rural counties do not have access to buprenorphine. Meanwhile, overdose deaths are an all-time high, reaching over 111,000 deaths in the 12 months ending in April 2022. These deaths are driven in large part by opioids like illicit fentanyl, but often combinations of drugs like stimulants, which are driving a “fourth wave” of the crisis.

The FDA approved buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder in 2002 along with a boxed warning, stating its potential for misuse and abuse, as well as extra requirements for prescribing. Buprenorphine and methadone work to reduce cravings associated with substance use. Studies consistently show MAT is effective in reducing overdose deaths and relapses — decreasing death by as much as 50 percent or more — and it is the standard of care for patients with substance use disorder. (Buprenorphine and methadone are also used to treat pain because they activate opioid receptors, partially and fully, respectively.)

Buprenorphine is “actually safer than a lot of things people feel maybe too comfortable prescribing every day.”

As overdose deaths continued to climb year after year, doctors and legislators called on the federal government to remove the extra hoops embedded in buprenorphine prescribing to save lives. Some championed the removal of the X-waiver and saw it as a necessary step in clearing the way for providers, especially in rural areas, to be able to prescribe MAT, while also eliminating a layer of stigma that additional restrictions created for patients.

“The fact that there was this whole system, this separate license requirement and training, created this false idea for prescribers and for everyone in general that it was somehow dangerous, more difficult to start and a more complicated drug that had a lot more risk,” Marino told Salon in a phone interview. “It’s actually safer than a lot of things people feel maybe too comfortable prescribing every day.”

In the past couple of decades, buprenorphine prescribing has increased, with the number of psychiatrists and addiction medicine doctors able to prescribe buprenorphine increasing from about 9 to 12 per 10,000 specialists between 2010 and 2018. Some argue it is essential to widen the prescriber base to include family medicine doctors and general practitioners, and the number of registered primary care doctors did increase from about 13 to 27 doctors per 10,000 across the same time period. Between 2006 and 2019, the number of buprenorphine doses in national supply also increased from 42 million to 577 million, according to a Washington Post analysis published last week.

However, just because providers have a waiver and the nation has a greater supply doesn’t mean clinicians are actually prescribing more buprenorphine. One 2020 study found only half of clinicians with waivers were writing buprenorphine prescriptions. In a survey published in July of this year, a majority of providers who had newly gotten access to prescribing buprenorphine said they hadn’t made the effort to prescribe it before because of the waiver and educational requirements. Yet the same group also reported a lack of patient demand as the most common reason that they hadn’t prescribed the drug since obtaining prescribing privileges.

That suggests additional barriers remain. Ten states have their own regulations for prescribing MAT, including urine screening for providers that prescribe buprenorphine, or counseling to be used with treatment. A 2019 survey of family medicine providers found only one in five were interested in treating opioid use disorder, suggesting stigma still largely influences whether patients are getting treatment.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

There are still regulations on the amount of buprenorphine that can be prescribed and the number of patients for which doctors with prescribing authority can write scripts. For the treatment of substance use, the recommended dose of buprenorphine is usually 16 milligrams, but recent data suggests that a higher dose of 24 milligrams may be more effective, especially as fentanyl has entered the drug supply and increased drug tolerances with its high potency. Nevertheless, even if providers prescribe buprenorphine, pharmacies do not always dispense it.

For this reason, some doctors have argued that buprenorphine should be allowed for sale without prescription, making the drug behind-the-counter, but far easier to obtain. “The incidence of any risks related to buprenorphine is likely low for individuals and the population; however, the magnitude of risk is high (overdose death) when it does occur,” Drs. Payel Jhoom Roy and Michael Stein wrote in JAMA in 2019. “On balance, this risk-benefit calculation favors making buprenorphine available under select regulation without a prescription.”

Meanwhile, methadone arguably has even stricter stipulations, making it one of the most heavily restricted drugs on the market, requiring patients to take treatment at federally-accredited facilities nationwide.

“There’s a weird double standard where you can use methadone for the treatment of pain and there’s no restrictions on it at all,” Marino said. “But when it comes to withdrawal and addiction treatment, it is not allowed to be prescribed by anyone at all as an outpatient and you have to instead go to a federally-accredited opioid treatment facility.”

Efforts are being made to reduce barriers that remain in prescribing MAT, with some medical schools embedding buprenorphine training into their curriculum. The Mainstreaming MAT Act was passed with the additional requirement that the Secretary of Health & Human Services will “conduct a national campaign to educate practitioners about the change in law and encouraging providers to integrate substance use treatment into their practices.”

Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a substance use researcher at the University of California, San Francisco who worked to get the X-waiver removed, said he is hopeful the next generation of practitioners will be more willing to incorporate addiction treatment into their practice regardless of specialty, but that these changes might be slow-moving.

“It’s going to take time,” Ciccarone told Salon in a phone interview. “Just because the policy changed doesn’t mean that there isn’t some cultural resistance to it.”

In recent years, many efforts have been made to abate the opioid overdose crisis, including changes in policy like the removal of the X-waiver, lawsuit payouts from pharmaceutical companies sued for their role in the overdose crisis and increased access to naloxone and other harm reduction policies. But these strategies are still ramping up to meet the massive need, Ciccarone said.

“We haven’t gotten there yet,” Ciccarone said. “Meanwhile, people are dying.”

In Tennessee, Garrett, who is uninsured, said he wishes there was more information about which if any, family medicine providers in his area prescribe MAT so he doesn’t have to shop around through multiple providers as he did with the pharmacies.

“I was excited that whenever I get out, I wouldn’t have to go to a Suboxone doctor, specifically, the costs would be lower and maybe I would only have to go once every month to see the doctor right off the jump,” Garrett said. “I figured I’d see some advertisements or see this in the news or hear about this from somebody … I haven’t seen any of that.”

Read more

about substance use