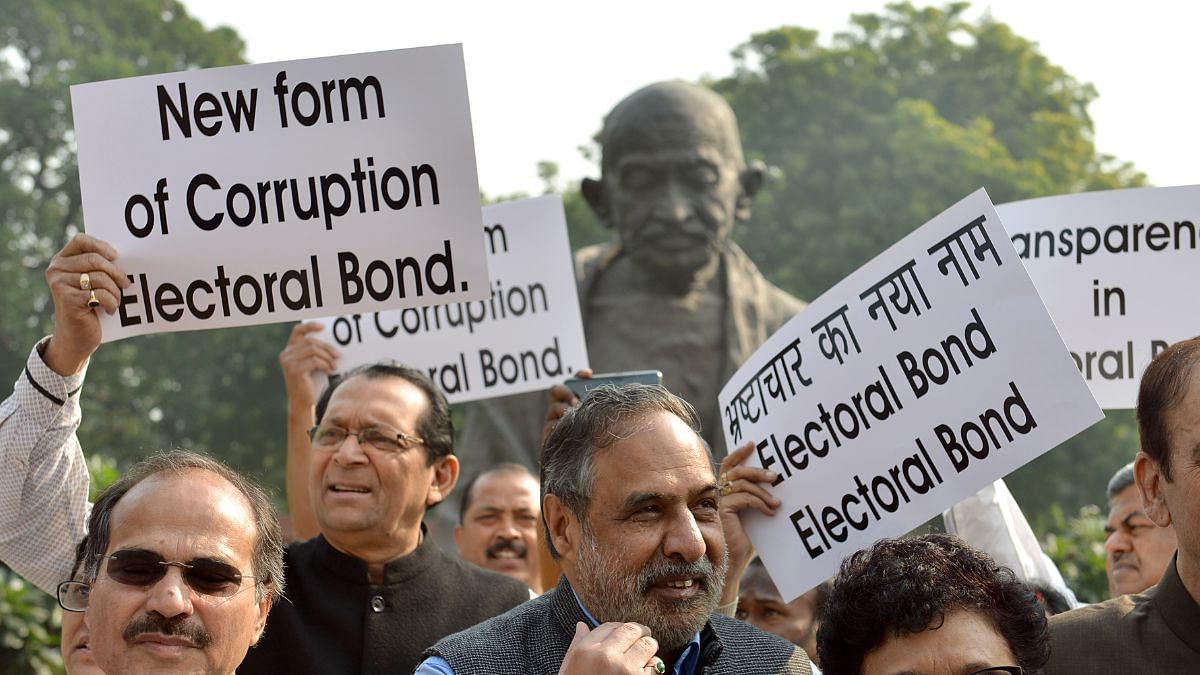

New Delhi: “Retrograde step towards transparency” — this is what the Election Commission of India (ECI) had said about the electoral bonds scheme in 2017, before it was introduced by the government in a bid to formalise anonymous corporate donations to political parties.

In its verdict delivered Thursday, setting aside the electoral bonds scheme, the Supreme Court noted that major apprehensions were raised by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the ECI in 2017 before the scheme was formalised.

“It is evident from the Amendment which has been made, that any donation received by a political party through electoral bond has been taken out of the ambit of reporting…this is a retrograde step as far as transparency of donations is concerned and this proviso needs to be withdrawn,” the ECI had then said.

To trace the background of the electoral bonds scheme, the Court laid out the context in which the electoral bonds scheme was introduced, including major apprehensions and concerns pointed out by the RBI and the ECI.

Also read: ‘Throwing baby out with bathwater’ — BJP reacts to SC declaring electoral bonds unconstitutional

What the RBI had said

In 2017, the finance ministry had proposed to the central bank that “scheduled commercial banks” should be permitted to issue electoral bonds for donation to political parties. However, the RBI objected to the proposal on the ground that the amendment would allow multiple “non-sovereign entities” (such as commercial banks) to issue bearer instruments, which would affect the RBI’s sole prerogative to issue such instruments.

The RBI had also said that if such notes are issued in bulk, it had the possibility of eroding faith in banknotes issued by the central bank.

RBI had also said that the objective of electoral bonds could be met via existing channels, such as cheque, demand drafts, and electronic/digital payments. “There is no special need for introducing a new bearer bond in the form of electoral bonds,” it had said.

However, the finance ministry had then reacted sharply, noting that the RBI had “failed to understand” the core purpose of electoral bonds, which was to ensure anonymity while ensuring donations were made only through taxpayer money. It had also then said that bonds being used as currency was unfounded, as such bonds only had a short duration.

In response, the RBI deputy governor suggested a “transitional” mechanism, including a limited life of 15 days of bonds and mandatory KYC compliance. Notably, the RBI suggested that the bonds must only be issued at RBI Mumbai and did not give in to the suggestion of issue by commercial banks.

Despite such suggestions from the RBI, the electoral bond scheme was circulated to the RBI for comments again which included the provision of issue of such bonds by commercial banks.

The RBI had again opposed the move, flagging issues such as public perception and it affecting the credibility of India’s financial system. It instead suggested issuing electoral bonds in electronic form for reasons of risk management, cost, and security.

“This [issue in scrips] will not leave any trail of transactions. While this would provide anonymity to the contributor, it will also provide anonymity to several others in the chain of transfer,” the RBI had said in 2017.

“The electoral bond may not only be seen as facilitating money laundering but could also be projected (albeit wrongly) as enabling it,” it warned.

What the ECI said

In a letter sent to the ministry of law and justice in 2017, the ECI, too, had opposed the electoral bonds scheme, raising questions about the transparency and the impact on political funding of political parties.

The ECI had said that where contributions through electoral bonds are not reported, even on examination of the contribution receipt statement of political parties, the originator cannot be ascertained.

It had even flagged concerns about the potential violations of The Representation of the People Act, 1951, which prohibits donations from government and foreign companies. The commission suggested that political parties must declare “party-wise” contributions in the profit and loss statement in a bid for transparency.

It said that the government’s removal of a cap on corporate funding of 7.5 percent of average net profits for preceding three years, which was imposed under the companies law, was not desirable.

“Notwithstanding anything contained in any other provision of this Act, a company, other than a government company and a company which has been in existence for less than three financial years, may contribute any amount directly or indirectly to any political party…,” the proviso said, imposing a cap of 7.5 percent on such donations.

It had pointed out several reasons for such concern, including the risk of use of black money for political funding through shell companies. Capped corporate funding could ensure that only profitable companies could donate, the ECI had said.

(Edited by Zinnia Ray Chaudhuri)

Also read: 10 important observations SC made while striking down electoral bonds scheme as unconstitutional