Even as INDIA flounders, with one ally after another either announcing plans to go solo or joining forces with the BJP, the Left parties remain steadfast in its faith on the usefulness of the alliance.

The Congress also appears unfazed as allies like the Trinamool Congress (TMC) threatened to walk out of the grouping over its closeness with the Left. “I won’t give you (Congress) a single seat until you leave the company of the Left,” TMC supremo Mamata Banerjee had warned the Congress.

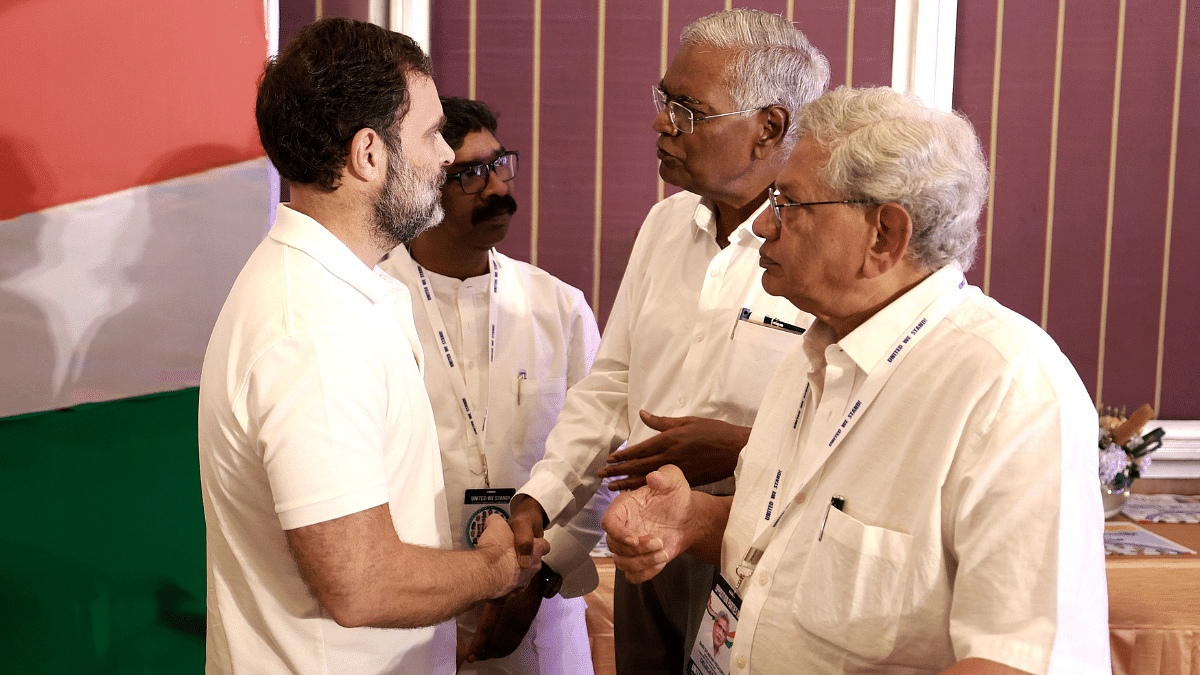

The Congress, however, chose to welcome Left leaders to Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Nyay Yatra in West Bengal. CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury is a prominent face at the high table of Opposition forums, often seen having intense discussions with Rahul.

Critics of the Congress maintain that, apart from the electoral battlefield where the two parties have allied time and again, the Left in recent years have continued to influence the Congress decision-making in matters of strategy, too.

“Who advises the Gandhis? Former AISA — students’ body of CPI(ML) — leader Sandeep Singh, who served as the JNUSU president in 2007, is the personal secretary of Priyanka Gandhi. Rahul seems comfortable in the company of CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury, who is often seen whispering into his ears like close aides do. It may sound like a stretch, but all these things are out there for people to make their own interpretations,” a TMC MP said.

The contradictions in Congress-Left dalliance have also been a matter of discussion — as also a source of embarrassment — for leaders of both the rival parties in Kerala whereas there is an understanding in West Bengal.

While CPI(M)’s Bengal secretary Mohammed Salim joined Rahul’s yatra in Murshidabad, the Congress stayed away from Kerala CM Pinarayi Vijayan-led protest against the Centre at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar.

The two parties together fought the 2016, 2021 assembly elections in Bengal. Previously, the Left Front, under the astute Harkishan Singh Surjeet, lent crucial outside support to the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2004. This continued till 2008, when it exited the alliance opposing the Indo-US civilian nuclear deal. Former CPI general secretary A.B. Bardhan shared a close rapport with UPA chairperson Sonia Gandhi during the UPA years.

Salim told ThePrint that both in West Bengal and at the national level, the CPI(M) and the Congress are fighting “common enemies Trinamool Congress and the BJP”. “We knew Mamata Banerjee will not stay in the (INDIA) alliance because she wants to help the BJP,” the West Bengal CPI(M) state secretary added.

Also Read: Sonia ‘welcomes’ Bharat Ratna to Narasimha Rao & Charan Singh but here’s why Gandhis won’t celebrate

‘Duality’ towards Congress

For the most part, however, a duality has marked the Left’s attitude towards the Congress over the decades. Professor of Contemporary Indian History at JNU, Aditya Mukherjee, said while the Communists worked very closely with the Congress’s Workers and Peasants Party, there was a marked shift in 1928 after the 6th Congress of the Communist International.

“Till then, the communists were following Lenin’s line of working on broad fronts representing anti-imperialist movements. But in 1928, under (Joseph) Stalin, the communists adopted a line that non-working class struggles against imperialism cannot work. In that characterisation, Congress was not a working class party. As a result, the communists lost their influence in the Congress at a time when it was leading popular movements such as the civil disobedience movement, anti-Simon Commission protests,” Mukherjee said.

Within five years, there was another change in position after the 7th congress of the Communist International. The Left leaders now started working with the Congress under the umbrella of the Congress Socialist Party, only to keep away from the Quit India Movement in 1942.

“The communists changed their position from saying that WW-II is an imperialist war, in which we will not participate, but once the Soviet Union was attacked, they said it is a People’s War. We must support the British because the Nazis, the Axis powers have attacked the Soviet Union,” Mukherjee said. But many grassroots communists continued to back the Quit India Movement despite the party’s flip-flops at the central level, he added.

Post Independence, while the Congress emerged as the biggest party in the 1952 polls, securing 364 seats with 45 percent votes, the undivided CPI finished second, albeit a distant one, winning 16 of the 49 seats it contested, polling 3.29 percent of the total votes.

The party’s performance, however, appeared impressive particularly considering that it not only stayed away from the Quit India Movement, but also dismissed Indian independence as a “sham” till 1951. Those were the years when Jawaharlal Nehru was a “running dog of imperialism” for the Communists.

It was only after B.T. Ranadive was replaced by Ajoy Ghosh as the general secretary of the CPI in 1951 when the party decided to work under the framework of parliamentary politics.

But the party’s antipathy towards the Congress remained as its socialist tilt and championing of a non-aligned foreign policy was yet to come to the fore. Unsurprisingly, the CPI viewed the Congress as a party beholden to “British and American imperialists”.

“What has come is the replacement of a British Viceroy and his councillon by an Indian President and his ministers, of white bureaucrats by brown bureaucrats, and a bigger share in the loot of Indian people for the Indian monopolists collaborating with the imperialists,” the CPI poll manifesto observed.

The Congress was not sparing in its hostility to the CPI either. So much so that in 1959, the Centre, with Nehru at the helm, dismissed the communist government in Kerala led by Chief Minister E.M.S Namboodiripad. Till date, the Congress faces criticism for the move.

The growing proximity of India with the Soviet Union and pursuit of bloc neutrality during the Cold War, led to a section of the CPI softening its stand towards the Congress, wrote author Praful Bidwai in his book ‘The Phoenix Moment: Challenges Confronting the Indian Left’.

But differences between the Soviet Union and China, coupled with contrasting positions on dealing with the Congress, led to a split in the CPI, with the pro-China and anti-Congress faction forming the CPI (Marxist) two years after the 1962 Sino-Indian war, he said.

“The Left’s growth as a force in national politics became dependent on its strategy of allying either with the ruling Congress or its major adversaries. Here the two parties took the opposite approach. This benefited both to an extent in different ways, but extracted a high price through ideological confusion and political disarray. The Left acquired the profile of a kingmaker in the 1990s, but committed a ‘historic blunder’ by refusing to lead a non-BJP, non-Congress government in 1996,” Bidwai wrote.

Also Read: Fresh jolt for INDIA bloc as AAP names 3 Assam candidates amid impasse with Congress — ‘We’re tired’

1970s & onwards

While the CPI(M) remained hostile to the Congress for a long time, the CPI not just supported the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi, but also allied with the Congress to form governments in Kerala for nearly a decade starting from 1970.

It was between 1977 and 1982 that the CPI revised its line, and that’s how the Left Front in West Bengal or the Left Democratic Front (LDF) in Kerala came about.

In 1989, the support of the Left parties and the BJP was instrumental in the formation of the V.P. Singh-led non-Congress National Front government. The United Front government between 1996 and 1998 also saw the participation of the Left parties.

At the same time, in states like West Bengal, Tripura and Kerala, the Left parties and the Congress remained adversaries. The gradual rise of the BJP, however, moved the needle, as the Left and the Congress again began collaborating, as seen in 2004 when the UPA came to power.

The Left parties did not just provide outside support to the UPA till 2008, but also played a key role in the formulation of policies ranging from RTI to MNREGA as Left-aligned activists and academics were part of the National Advisory Council (NAC) which guided the government on policy matters.

The NAC was disbanded after the Narendra Modi government came to power in 2014.

Prof. Mukherjee attributes the many shifts in the Left’s position vis-a-vis the Congress to the fact that “they have not questioned their basic theoretical premises.”

“So even when they shift away from that sectarian dogmatic position (of not allying with the Congress), they do it pragmatically. They do not do it by reexamining their position. Euro Communism tried to question the dogmatic line. They gave up the notion of the dictatorship of the proletariat. The communists theoretically never undertook that exercise. While their leadership may occasionally do the pragmatic thing, their cadre is still trained in a completely different theory. The communist mind still remains sectarian and that keeps resurfacing and unfortunately damages their long-term impact,” he said.

Commenting on the tie-up between the Left and the Congress in Bengal in 2016, Jadavpur University Prof. Om Prakash Mishra, who as a Congress leader was a key player in the formation of the alliance, said despite objections from the state leadership, he sought to convince the party’s high command of its feasibility.

The two parties, however, stopped short of calling their partnership an alliance, dubbing it as a seat-sharing agreement. Eventually, the TMC won 211 of the 294 total assembly seats, the CPI(M) 26 and the Congress 44, with a vote share of 44.9, 19.75 and 12.25 percent.

Mishra, who later joined the TMC, pitched a Left-Congress alliance in Bengal even for the 2019 general elections, but it found no takers. In 2018, the differences in the CPI(M) regarding cooperation with the Congress came to the fore, with Yechury advocating that the possibility of an “understanding” be kept open, even as the lobby led by former party general secretary Prakash Karat opposed it.

Eventually, the CPI(M)’s 22nd and 23rd Party Congress in 2018 and 2022 adopted the line that given its basic link to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) — according to the CPI(M) website — the BJP is the “main threat. So both the BJP and Congress cannot be treated as equal dangers. However, there cannot be a political alliance with the Congress party.”

It effectively meant that the CPI(M) kept the door open for seat-sharing agreements.

In the 2021 West Bengal polls, the Left parties and the Congress shared seats along with the Indian Secular Front (ISF). But it came a cropper again, as the TMC stormed back to power, and the BJP emerged as the principal opposition party. Both the Congress and the Left Front drew a blank, and their combined vote share was 7.66 per cent, down by 24 percentage points from 2016.

According to political analyst Snigdhendu Bhattacharya, the Congress and the Left Front cannot put up a solo show in West Bengal. “Congress is limited to Malda and Murshidabad, but it has lost ground to the TMC since the 2019 Lok Sabha polls and that is reflected in the 2021 assembly polls data. The Congress alone is unlikely to win a single seat. This winnability perception influences supporters,” he said.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Tenacious fighter, gritty — how ‘captain’ Minakshi Mukherjee is emerging as Left’s hope in Bengal