“Mr. Kuok has mentored me on being a good custodian of such an important Hong Kong institution as the South China Morning Post. I want to send my warmest congratulations to him on his 100th birthday,” Tsai said.

Although a Hong Kong resident since the 1970s, Kuok’s 2017 memoir revealed his enduring affection for Malaysia, despite his disdain of its preferential treatment of the majority Malays.

Kuok, the youngest of three sons from a prosperous family, faced challenges in his rise to corporate success. After his father’s death in 1948, his brothers and cousin took over the family’s rice distribution business.

Kuok referred to his “humiliation … at the hands of the banks” after taking over the business. “Now, if that doesn’t drive you forward in life to make as much money as possible so you can thumb your nose at those bankers, then what will?”

By the 1960s the tycoon had diversified his business and was known as the “Sugar King of the East”. Today, Forbes estimates his wealth, spanning a region-wide property-to-logistics empire, at US$10.3 billion, making him Malaysia’s wealthiest man.

His Shangri-La Group, established in 1971, now owns, operates, and manages over 100 hotels and resorts in 78 destinations.

Mother, Mao, and Hong Kong taxes

Mother, Mao, and Hong Kong taxes

Lee sought Kuok’s counsel during the early years of his 31-year stint as prime minister. When Lee died at age 91 in 2015, Kuok hailed him as “the greatest Chinese outside mainland China”.

Weeks after the election, Kuok met Mahathir – serving his second stint as premier after holding that position from 1981 to 2003 – in the prime minister’s office and saluted the veteran politician in front of cameras, saying: “I salute you, you’ve saved the country”.

Mahathir, who appointed Kuok to his council of advisers, replied: “We need your help now.”

Malaysia-Singapore Airlines, Siamese twins set for separation

Malaysia-Singapore Airlines, Siamese twins set for separation

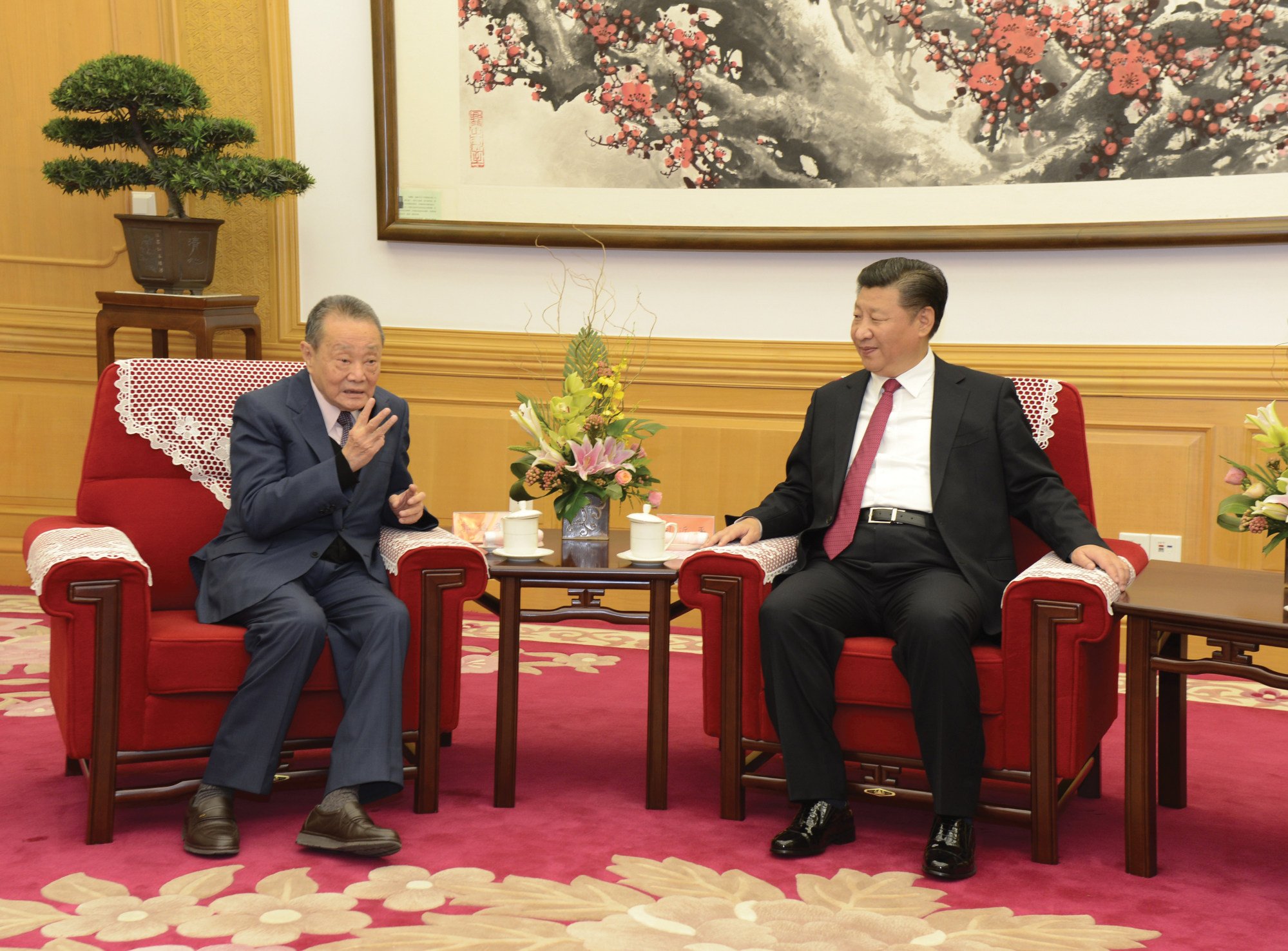

On the Chinese mainland, Kuok’s vast commercial interests across industries are underpinned by his careful nurturing of ties with Beijing from the early years of his business – when he traded rice and sugar with the behemoth Asian economy.

That same year, Kuok’s Kerry Group acquired a controlling interest in the South China Morning Post from Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, holding it for 22 years, until 2015.

During the Kerry Group’s stewardship of the Post, Kuok once said: “l am a firm believer in freedom of the press and I am also a firm believer that the Hong Kong press and media must work for the good of Hong Kong.”

The mega development was also a major vote of confidence by Kuok in the country that earned him a lot of goodwill.

In his memoirs, Kuok referred to the venture as “one of the best investments anybody has made in China”, saying it opened the floodgates for others to also bet on the country’s property market.

He also revealed how his love for Malaysia remained steadfast even as he described himself as a patriotic Chinese who felt duty bound to help China, the birthplace of his parents, during its economic transformation and rise on the global stage.

The very private father of eight dedicated the book to the two guiding lights in his life. The first was his Fuzhou-born mother Tang Kak Ji, whom he called the “true founder” of the Kuok empire and the reason for his lifelong interest and patriotism towards China, and the second, his brother William, “a great human being who died too young”.

Known for his humility and compassion as much as for his business acumen and charisma, Kuok ended his memoir with the contemplative question, “What is wealth for?”