Organic chemicals, primarily composed of carbon and hydrogen, underly all of life. They’re also widespread in the Universe, so they can’t be taken as a clear signature of the presence of life. That creates an annoying situation regarding the search for evidence of life on Mars, which clearly has some organic chemicals despite the harsh environment.

But we don’t know whether these are the right kinds of molecules to be indications of life. For the moment, we also lack the ability to tear apart Martian rocks, isolate the molecules, and figure out exactly what they are. In the meantime, our best option is to get some rough information on them and figure out the context of where they’re found on Mars. And a big step has been made in that direction with the publication of results from imaging done by the Perseverance rover.

Ask SHERLOC

The instrument that’s key to the new work has a name that pretty much tells you it was designed to handle this specific question: Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics & Chemicals (SHERLOC). SHERLOC comes with a deep-UV laser to excite molecules into fluorescing, and the wavelengths they fluoresce at can tell us something about the molecules present. It also has the hardware to do Raman spectroscopy simultaneously.

Collectively, these two capabilities indicate what kinds of molecules are present, though they can’t typically identify specific chemicals. And, critically, SHERLOC provides spatial information, telling us where sample-specific signals come from. This allows the instrument to determine which chemicals are located in the same spot in a rock and thus were likely formed or deposited together.

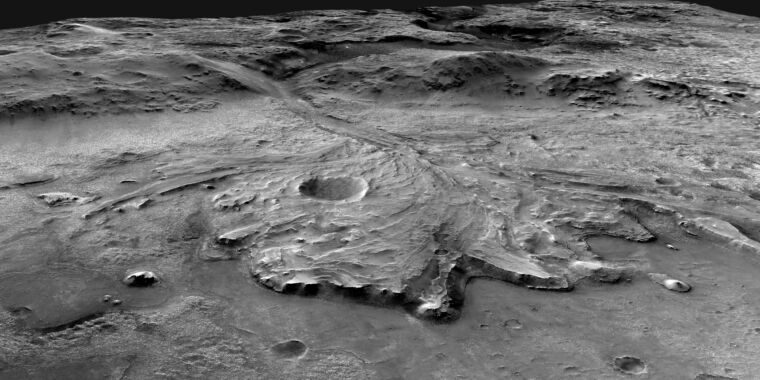

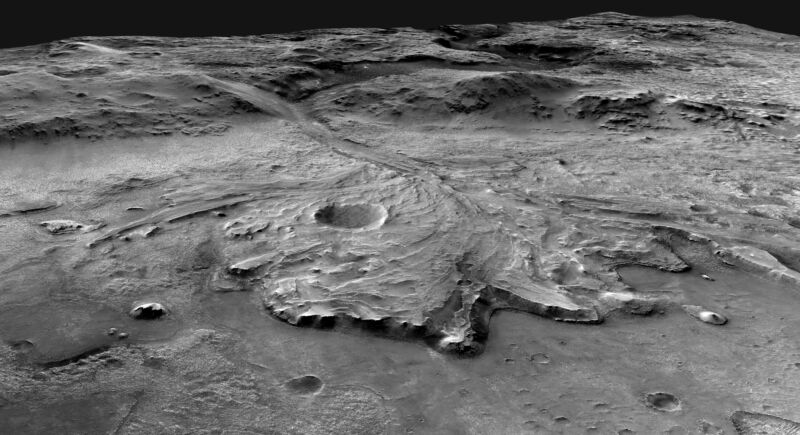

SHERLOC can sample rocks simply by being held near them. The new results are based on a set of samples from two rock formations found on the floor of the Jezero crater. In some cases, the imaging was done by pointing it directly at a rock; in others, the rock surface, and any dust and contaminants it contained, was abraded away by Perseverance before the imaging was done.

SHERLOC identified a variety of signatures of potential organic material in these samples. There were a few cases where it was technically possible that the signatures were produced by a very specific chemical that lacked carbon (primarily cerium salts). But, given the choice between a huge range of organic molecules or a very specific salt, the researchers favor organic materials as the source.

One thing that was clear was that the level of organic material present changed over time. The deeper, older layer called Séítah only had a tenth of the material found in the Máaz rocks that formed above them. The reason for this difference isn’t clear, but it indicates that either the production or deposition of organic material on Mars has changed over time.

Regional differences

Between the different samples and the ability to resolve different regions of the samples, the researchers were able to identify distinct signals that each occurred in many samples. While it wasn’t possible to identify the specific molecule responsible, they were able to say a fair bit about them.

One signal came from samples that contained a ringed organic compound, along with sulfates. The most common signal came from a two-ringed organic molecule and was associated with various salts: phosphate, sulfate, silicates, and potentially a perchlorate. Another likely contained a benzene ring associated with iron oxides. A different ringed compound was found in two of the samples.

Overall, the researchers conclude that these differences are significant. The fact that distinct organic chemicals are consistently associated with different salts suggests that there were either several distinct ways of synthesizing the organics or that they were deposited and preserved under distinct conditions. Many of the salts seen here are also associated with either water-based deposition or water-driven chemical alteration of the rock—again, consistent with the processes involved changing over time.

Collectively, the researchers say this argues against the organic chemicals simply having been delivered to Mars on a meteorite.

Again, the instrument can’t tell us what the chemicals are, so there’s no way to know whether any of the processes involved in creating these deposits involved living things. But that could eventually change since some of the rocks that SHERLOC examined have been used to obtain material for the planned Mars sample return. If that mission ever happens, then we’ll finally have the chance to isolate and study the chemicals on Earth.

Nature, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06143-z (About DOIs).