Update 2:32 p.m. EDT: Added mission details.

For a fourth time in a little more than a year, SpaceX launched a test mission of its massive Starship rocket from its development facility in southern Texas called Starbase. The launch, dubbed Flight 4, push the launch vehicle towards its goal of being a mostly reusable rocket.

Similarly to the previous three launches, Flight 4 did not include a payload and flew a suborbital trajectory. Unlike the preceding missions, Flight 4 saw a soft splashdown of the Super Heavy Booster (Booster 11) and of the Starship upper stage (Ship 29). Liftoff took place at 7:50 a.m. CDT (8:50 a.m. EDT, 1250 UTC), near the opening of a 120-minute window.

On Wednesday, SpaceX stacked the Ship 29 on top of Booster 11 to create the 121 m (397 ft) Starship rocket. In a post on X (formerly Twitter) on June 1, SpaceX founder Elon Musk stated that “the main goal of this mission is to get much deeper into the atmosphere during reentry, ideally through max heating.” In the aftermath of the mission, he celebrated the reentry of Starship “despite [the] loss of many tiles and a damaged flap.”

During Flight 3, the upper stage began to roll uncontrollably, preventing the vehicle from performing a relight of one of its six Raptor engines. However, thanks to its ability to connect to the Starlink satellite internet network, another part of SpaceX’s business, the rocket was able to stream back high definition camera views showing its reentry through a blanket of plasma.

“The lack of attitude control resulted in an off-nominal entry, with the ship seeing much larger than anticipated heating on both protected and unprotected areas,” SpaceX said in a post-launch blog. “The most likely root cause of the unplanned roll was determined to be clogging of the valves responsible for roll control. SpaceX has since added additional roll control thrusters on upcoming Starships to improve attitude control redundancy and upgraded hardware for improved resilience to blockage.”

Meanwhile, the Super Heavy Booster from the last flight also prematurely shut down six out of 13 Raptor engines used during the boostback burn, which remained offline when it attempted to perform a landing burn.

“The booster had lower than expected landing burn thrust when contact was lost at approximately 462 meters in altitude over the Gulf of Mexico and just under seven minutes into the mission,” SpaceX stated. “The most likely root cause for the early boostback burn shutdown was determined to be continued filter blockage where liquid oxygen is supplied to the engines, leading to a loss of inlet pressure in engine oxygen turbopumps.”

“Super Heavy boosters for Flight 4 and beyond will get additional hardware inside oxygen tanks to further improve propellant filtration capabilities.”

Now, with the success of Flight 4, Musk teased ahead to an ambitious milestone for Flight 5: catching the Super Heavy Booster using the launch tower’s so-called “chopsticks.”

I think we should try to catch the booster with the mechazilla arms next flight!

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) June 6, 2024

Eyes on the Moon

Flight 4 was an important mission not only for SpaceX, but also for NASA. The rocket will take center stage when the agency embarks on the Artemis 3 mission, which is currently targeting September 2026.

Lisa Watson-Morgan, the manager of the Human Landing System program, and her team continue to work alongside SpaceX to understand the development of the rocket that will serve as the Moon lander for the yet-to-be-named astronauts of the Artemis 3 and Artemis 4 missions. She spoke with Spaceflight Now in the lead up to the Flight 4 launch.

“It was great to see the lessons that came out of [flights] one and two and to see how that was employed either through manufacturing, production, through operations of how Flight 3 was conducted,” Watson-Morgan said. “There weren’t any issues around Raptor. No fires and a lot of good consistency, frankly, around the engines. When you get all those engines to light up, for us, it was a significant win.”

She noted that while the Raptor relight on the upper stage during Flight 3 wasn’t able to be accomplished, there’s still plenty of time to achieve that milestone. Watson-Morgan said they would need to see it demonstrated either in the back half of 2024 or in early 2025.

“As SpaceX continues to mature their Raptors, because they’re working through their design and development, as they do that, they’re making modifications and adjustments and changes,” Watson-Morgan said. “And all of that’s getting incorporated into an updated build sequence.”

One of the successes that Watson-Morgan and NASA took note of was the propellant transfer, which shifted liquid oxygen (LOX) from the ship’s header tank to the main upper stage LOX tank. That was designed to fulfill a $53.2 million Tipping Point contract with NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD), which had a requirement to demonstrate the transfer of 10 metric tons of propellant.

Watson-Morgan said that while the HLS office was not directly involved with that, representatives from STMD echoed the opinion of SpaceX in that it was a successful demo. It’s the first step in being able to conduct a ship-to-ship propellant transfer, one of the main components of the SpaceX mission for Artemis moon landings.

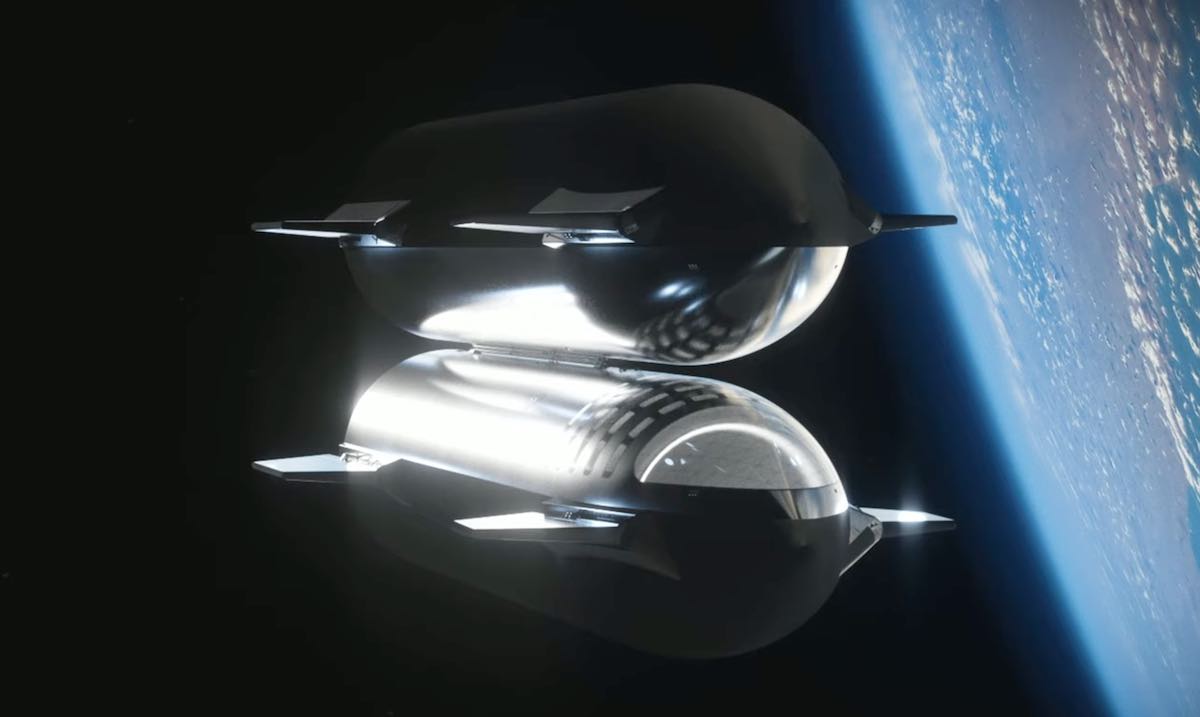

SpaceX’s concept is to launch a tanker version of the ship upper stage into low Earth orbit. They would then launch a series of ships to dock with the tanker and transfer propellant into it, which would in turn, shift that over to the HLS version of Starship before it heads off to the Moon.

“Prop transfer is really the key to the portal to the rest of the universe. It genuinely is. It’s the key to Mars, it’s the key to the South Pole and really, that is our long pole and we’re doing all we can to get ready for that, to help SpaceX with that,” Watson-Morgan said. “In addition, we’re doing all we can to help Blue Origin with it because they have that as well in their concept.”

The number of fueling flights heading up to the tanker doesn’t have a hard and fast number at this point, Watson-Morgan said, because it’s not entirely clear how much propellant needs to be transferred.

“It’s contingent on the six of the tanks. It’s contingent on how much how much do we want to transfer. It’s contingent on what all are the other objectives that we want to prove out and how long do we want to make the demonstration of the flight test?” Watson-Morgan said. “And so, it could be just a couple and it could be more than a couple. And so, it all depends on our objectives.”

“One thing that I appreciate much about SpaceX is that they are willing to be open and fluid with objectives and open to more objectives, if NASA believes we need them, depending on the timing.”

While she was limited on what she could say about it, Watson-Morgan also mentioned that SpaceX is developing a smaller thruster-style engine to help with the prop transfer demonstration. She said a development milestone on that is coming up later this year.

“Our team has been very impressed. They’ve developed this engine within less than half a year and it’s, so far, been performing well,” she said.

Starship expansion

Part of the timing for the propellant transfer will hinge on being able to launch multiple Starship missions from more than the one launch tower SpaceX currently has. The company is in the process of building a second tower down at Starbase.

To that end, they manufactured additional segments and components at their facilities at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida and have barged them down to Texas. A collection of four tower segments shipped earlier this year and this week, they loaded two more segments onto the barge, along with the tower’s so-called “chopsticks” and their elevator system supports.

Watson-Morgan said the propellant transfer mission could be conducted from two towers at Starbase, but NASA is very interested in making sure that Starship launch capabilities come online at KSC as well. Next week, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) will host public scoping meetings to gather input on allowing around 44 Starship launches per year from historic Launch Complex 39A.

Simultaneously, the Department of the Air Force is also doing a similar assessment for Starship launches from either Space Launch Complex 37, which is the former launch site of United Launch Alliance’s (ULA) Delta 4 Heavy rocket, or from a proposed new launch pad called SLC-50.

“We definitely want to see that. We have to see it by the uncrewed demo for sure and clearly, we’d like to see that before to make sure that everything checks out,” Watson-Morgan said. “We will go ahead and have pad checkouts and all that and operational readiness reviews in advance of it.”

Part of SpaceX’s HLS agreement with NASA is that it will perform an uncrewed landing of Starship on the Moon prior to the Artemis 3 mission.

Humans in loop

As they’re developing the human-rated version of Starship, they’re also gathering input from Astronaut Office, which is located at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Watson-Morgan, referring to them as “the crew” for shorthand, said the office offers insight and opinions on the functionality of certain parts of the vehicle, like interface, control system and location of handles.

She said the HLS office mainly works with astronauts Raja Chari and Randy Bresnik, the latter of whom has been a part of the process “since the very beginning.” Watson-Morgan said that they also have members of the astronaut office on their control board.

“We have a Human Landing System control board, where any requirements changes or updates or how things are implemented get to go through their formal board actions and the crew’s a voting member,” she said.

On April 30, at the SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California, NASA astronaut Doug “Wheels” Wheelock and Axiom Space astronaut Peggy Whitson performed the first integrated test of Axiom’s pressurized spacesuits alongside mockups of a Starship elevator and the airlock.

“Overall, I was pleased with the astronauts’ operation of the control panel and with their ability to perform the difficult tasks they will have to do before stepping onto the Moon,” said Logan Kennedy, lead for surface activities in NASA’s HLS Program, in a statement. “The test also confirmed that the amount of space available in the airlock, on the deck, and in the elevator, are sufficient for the work our astronauts plan to do.”

Shorter turnaround?

Through the Starship test campaign, SpaceX achieve shorter and shorter turnaround times between launches. That’s partly due to accomplishing more each time in a less destructive way, but also thanks to work being doing by the FAA.

Flight 2 came just 212 days after Flight 1, Flight 3 was 117 days after Flight 2 and Flight 4 comes just 84 days after Flight 3. Watson-Morgan said her understanding is that SpaceX would like to reach a monthly launch cadence at Starbase, but knows that they’ll want to infuse the learning of previous flights into successive ones, which may take more time.

“Even if it’s every two to three months, that’s still quite an achievement for a test campaign and each one of these tests will buy down different risks,” Watson-Morgan said. “For a NASA standpoint, seeing each one of those launches, we’ll get a little deeper insight into how all the engines act, how they’re performing, with respect to the ISP (specific impulse) and so, we will have that.”

In its approval of the launch license modification allowing for Flight 4, the FAA said that SpaceX gave it three scenarios for Starship entry at the end of the mission “that would not require an investigation in the event of the loss of the vehicle.”

“The FAA approved the scenarios as test induced damage exceptions after evaluating them as part of the flight safety and flight hazard analyses and confirming they met public safety requirements,” the agency said in a statement. “If a different anomaly occurs with the Starship vehicle an investigation may be warranted as well as if an anomaly occurs with the Super Heavy booster rocket.”

That language, coupled with a good performance of Flight 4 could open the door for a much faster announcement of a Flight 5 mission.