Only SpaceX launches more rockets from U.S. soil each year than Rocket Lab. Firmly established as a key player in the aerospace industry, the company isn’t just sitting back. Its upcoming Neutron rocket will push its capabilities even further, as it endeavors to expand its identity beyond just being a launch provider.

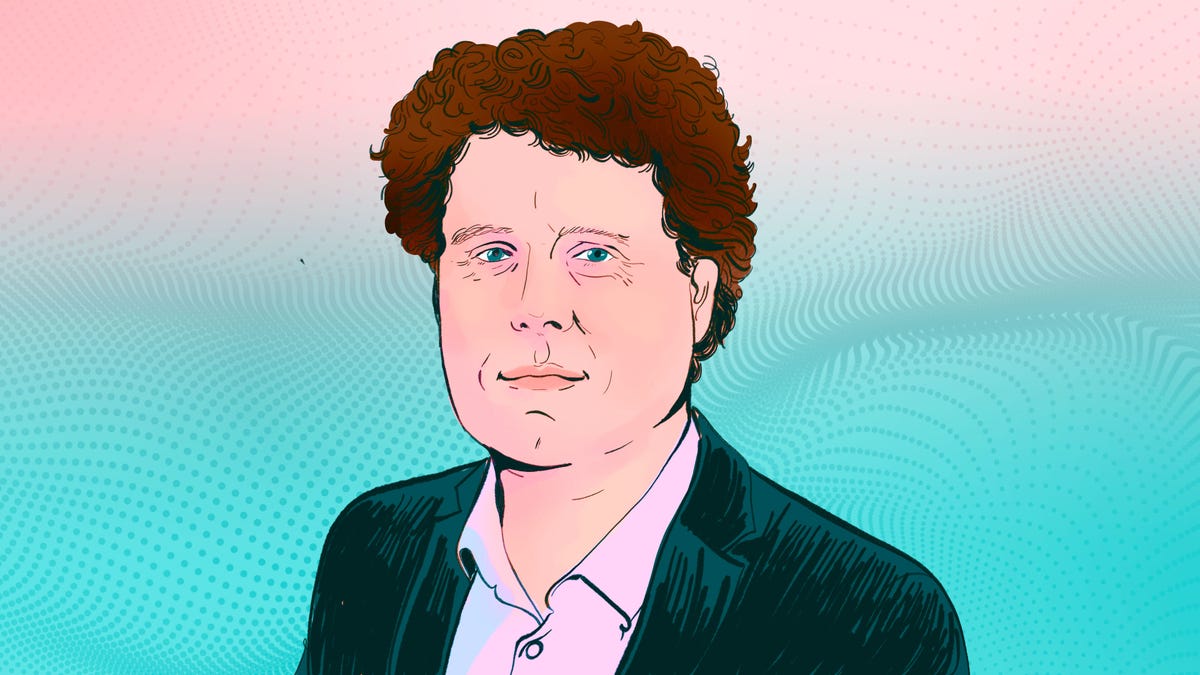

Rocket Lab, founded by New Zealander Peter Beck in 2006, routinely uses its light-lift Electron rocket to deliver satellites to Earth orbit, forging contracts with NASA, the U.S. Space Force, the National Reconnaissance Office, Capella Space, Spire Global, BlackSky, and Telesat, among others. To date, Electron has launched more than 160 satellites to space. Now based in Long Beach, California, Rocket Lab is very good at what it does.

The company went public in August 2021 (trading on Nasdaq as RKLB), and stands out as the only commercial firm capable of conducting rocket launches from two continents, operating in New Zealand’s Māhia Peninsula and Virginia’s Wallops Flight Facility. So far in 2024, Electron has flown on four missions, with as many as 20 missions planned for the coming months.

Rocket Lab’s progress can be attributed in large part to its smart innovations. This includes Electron, the first rocket with a full carbon-composite build, and the Rutherford engine, the first 3D-printed and electrically pumped rocket engine. Rutherfords are also the first 3D-printed engines to fly on multiple space missions. Rocket Lab initially wanted to use helicopters to catch falling Electron boosters, but it switched to ocean recovery after discovering that the boosters were fine after splashing around in the salty water; the company is steadily inching closer to rocket reusability. As for Photon, it’s proving to be a versatile and reliable satellite bus, capable of deploying an assortment of missions, including NASA’s CAPSTONE cubesat, which is currently in orbit around the Moon.

The company is in the midst of building a fully reusable medium-lift launch vehicle. Dubbed Neutron, the rocket will include the unique “Hungry Hippo” fairing design and the reusable Archimedes engine. Beck, the CEO and CTO of Rocket Lab, envisions Neutron as a “mega-constellation launcher,” and it’s slated to fly in late 2024, though next near seems more plausible.

Beck envisions Rocket Lab as more than just a launch provider; he sees it as an end-to-end space company. This vision extends to creating satellites and spacecraft components, as well as managing space assets. I recently spoke to Beck about what’s happening at Rocket Lab and what’s next for the company.

George Dvorsky, Gizmodo: What is your background?

Peter Beck: My background is unusual to say the least. As you can probably tell from my accent, I’m not from America. I was born in a small town at the bottom of New Zealand, which is not known for its aerospace industry. In fact, it had zero before I started Rocket Lab. So a very non-traditional start. I joke among my peers that I’m the only non-billionaire rocket CEO. Most of my competitors fall into that category. For us, it was always about creating this capability and doing it initially in a country and in an area that we thought was tremendously underserved. So, yeah, a very nontraditional background, though I am a mechanical engineer.

Gizmodo: How do you foster a culture of innovation at Rocket Lab, and how do you encourage your team to think creatively about some of the more complex challenges that are frequently placed before them?

Beck: We have our internal methodologies for developing technology, and part of it is making sure that we fail fast on the small stuff. We don’t like to fail fast on the big stuff, but fail fast on the small stuff. What that means is, we’ll do a whole bunch of small tests at the component level, for example, and then by the time it gets to the whole system level we don’t expect failures.

We’re not afraid of taking big swings at innovation. We were the first to put a 3D-printed rocket engine in orbit. And of course, not everybody 3D prints their rocket engines. When we announced the Rutherford engine in 2015, the current state of the art of 3D printing was cats, prosthetics, and bottle openers, so nobody really took it that seriously that we were going to print a rocket engine.

We’re not afraid to take on what we think are going to be transformative innovations or technologies and give them a crack, provided they have big outcomes. We don’t do things to try and get Wikipedia pages, but we do things because we think they’re going to have big outcomes. Same with our carbon composite rocket—we were the first to put a carbon composite rocket into orbit, once again, not for any other reason, but we could see that that was going to be a huge performance advantage for us both now and in the future, and that’s proven to be true.

One other thing that I drive home to everybody—probably the hardest—is to make beautiful things. And that stems from my belief that, if you create something that is at least aesthetically beautiful, then the chances of it working is significantly higher than if it isn’t. If you make it beautiful, at least it looks good. If you made it and it’s ugly and it doesn’t work, then you’ve achieved absolutely nothing—you’ve got something that doesn’t work and doesn’t look good. We really care about quality engineering and building beautiful things, and innovation flows deeply through the business. We’re willing to take big swings at things that we think are going to have big payoffs.

Gizmodo: Looking at the next decade in terms of space technology innovation, what role do you see Rocket Lab playing in this landscape?

Beck: If we play our cards right, we play a big one. Our view of the space industry was unique as of a few years ago, and we’re starting to see some followers. But our view always was that the large space companies of the future are not going to be just solely a launch company or just solely a satellite company. They’re going to be a merging of two, where things get blurry.

At the end of the day, nobody in the space industry goes home and salivates about how beautiful the rocket they bought was, or how good looking their satellite was—they salivate over the fact that they have something in orbit that’s generating revenue, and truth be known, everything prior to that is just a necessary evil. So if you can cut out all of the junk in between an idea and generating revenue from orbit, then you bring tremendous value to a customer. Our view is that the large space companies of the future are going to be combined launch and infrastructure companies. And when I say infrastructure, I mean companies that can build the satellites and operate the satellites, as well as launch them.

We’re starting to see a wider range of players entering the space domain—those who are, I would say, less traditional in the context of space. They don’t want to know about the thermal bias on a radiator on a satellite. They don’t need to learn about that stuff—they just want signal from space, and the easier you can make that, the more successful you’ll be.

Gizmodo: What are some of the most critical emerging technologies in the space industry, and how is Rocket Lab adapting to or driving these particular trends?

Beck: I think you’re starting to see some really interesting trends. One is internet from space, but I think it’s yet to be proven whether or not that’s going to be viable, but certainly a lot of capital is flowing into that. I think another interesting one is direct-to-mobile; being constantly connected through the space infrastructure with direct mobile is super interesting. Another one is pharmaceutical manufacturing from space.

As to how we’re playing in those things, we have a finger in every pie. Right now, I would say to you that obviously we build and launch rockets, we build and launch satellites. Two-thirds of our revenue comes from our satellite manufacturing arms or satellite component arms. Through those, we’re deeply involved in play in all of those kinds of elements.

Gizmodo: Are there specific technologies you’re hoping to develop in the coming decade?

Beck: The most important thing to recognize about the space industry is that it is a cottage industry full of little shops. So everywhere you look in the space industry, it’s upscale. The development of technology is one element, and the other is scaling these technologies in an industry where they are so bespoke and unique. That’s really where the majority of the challenge lies.

I don’t think there are massive holes in technology development, except, perhaps, in the area of propulsion. And I guess the reason why I pick on propulsion is that we’ve been burning dinosaurs since the beginning of the Space Age. By the late 1950s, we achieved the maximum performance you could achieve out of burning fuels. All we’ve done is increase the pressures in the chambers and increase the size of the engines, and that’s because we’ve reached chemical equilibrium on combustion. There is nothing more to give. To me personally, the biggest innovation that will set the stage for the most substantial change in the space industry will be a revolution in propulsion. Now, I don’t know what that revolution will be, but we are thinking about it as hard as we can. Until we get away from burning propellants, we’re locked to building ever larger rockets.

Gizmodo: Why is 3D-printing so important to Rocket Lab?

Beck: It’s all about manufacturing—it enables some geometries that weren’t possible under other manufacturing techniques. For us, it also enabled the innovation cycle to be much, much faster, where we could try new designs quickly and iterate much more rapidly. 3D printing is really ideal because a large volume in the space industry is like a thousand of something, which is not even a sample run in most other parts of manufacturing.

Gizmodo: What advice do you have for young entrepreneurs and innovators looking to make their mark in the space industry?

Beck: Well, this is going to sound almost a little bit CEO-y, but it needs to be said: Do something that people want, that people need. The space industry is littered with businesses that have failed, where a technologist has come up with a wonderful piece of technology, built a business around it, and then tried to figure out how to make a viable business around this cool piece of technology.

Nowhere is this more true than in the space industry, where someone will create a new kind of solar panel, spend their life on it, and raise a whole lot of money. And then at the end of the day, the market is tiny and nobody cares.

So my advice would be, if you’re entering the space industry, think about the technologies that people really need, not the technologies that are really cool. Instead, think about technologies that have scale, and go after those because there’s nothing worse than creating something for an industry that is, by its very nature, incredibly niche and small.

For more spaceflight in your life, follow us on X and bookmark Gizmodo’s dedicated Spaceflight page.