3.5/5 stars

It amounts to both an innocuous introduction and a potential spoiler to point out that The Goldfinger is based on the real-life financial scandal of the Carrian property empire, which enjoyed a meteoric rise to power in the early 1980s but suffered a spectacular collapse in 1983, following an economic downturn the previous year.

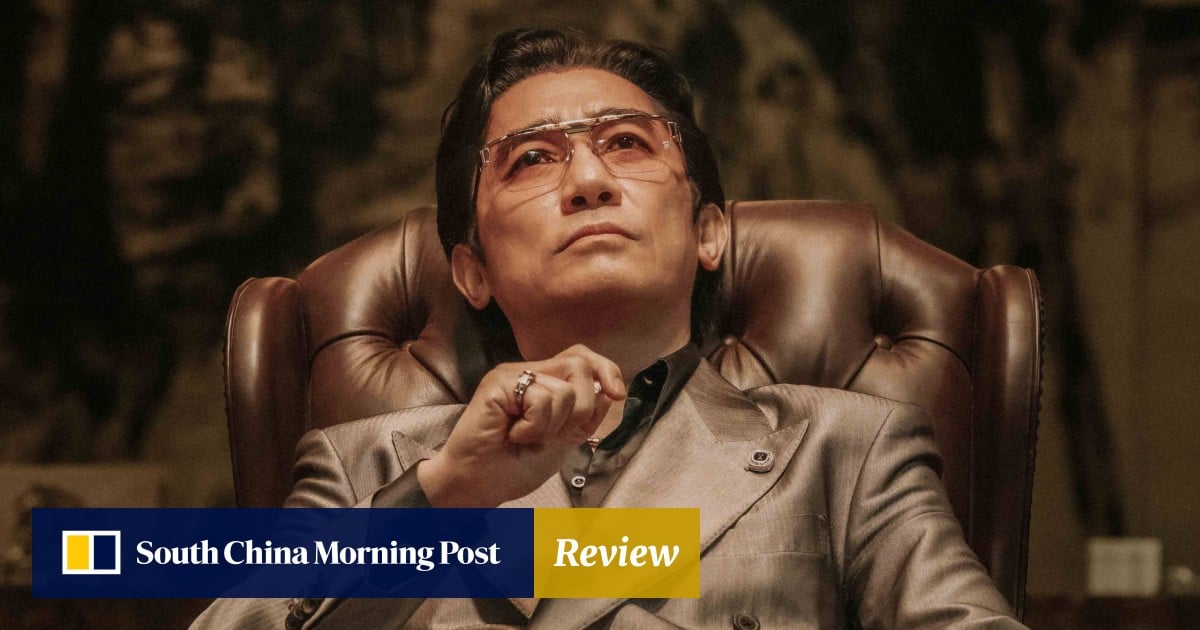

Leung has a field day hamming it up as the charismatic con man Henry Ching – a stand-in for Carrian founder George Tan, who arrived in Hong Kong as a bankrupt Singaporean in the 1970s and swiftly built up his own international conglomerate via an extraordinary series of investment gambles, fraud and corruption.

Some of The Goldfinger’s most intriguing scenes arrive early, as when Ching swindles Tai Bo’s cocky property investor out of millions; or when he hires his first secretary, Carmen (Charlene Choi Cheuk-yin), and names his company after her – only to push her into the arms of Michael Ning’s influential stockbroker to further his scheme.

Next to Ching’s dramatic efforts to attract new partners – with bribes and women – and secure outrageous bank loans, the relentless quest of Independent Commission Against Corruption senior investigator Lau Kai-yuen (Andy Lau in a glorified supporting role) to bring him to justice pales in entertainment value.

Similar to Project Gutenberg, much of The Goldfinger is narrated in flashback through recollections of Ching’s associates under questioning, which often take the form of tall tales that they spin on behalf of the cigar-chomping protagonist out of a mix of admiration and fear.

While Ching impishly declares to Lau that he is just a frontman for the far more powerful people behind his back, the film never bothers to hypothesise on how exactly he has positioned himself in the middle of this stranger-than-fiction series of events – and Chong is content to stick to many of the known facts with his story trajectory.

A visually engrossing tale of corporate sleaze that brings a bygone era lavishly back to life, The Goldfinger may come across as little more than a glossy re-enactment of the news stories for those who actually remember them.

For the uninitiated viewer who goes into Chong’s film without any knowledge of its key inspirations, however, the writer-director’s decision to paint Henry Ching as an enigma unto itself may very well feel like a bewildering cop-out in the end.