To gauge the popularity of contemporary Korean literature in China today, one need not look past Kim Cho-yeop’s short-story collection If We Cannot Move at the Speed of Light (2019).

Published in Chinese in 2022, this year it won the Korean science fiction writer both the Chinese Nebula Award for Best Translated Work and the Galaxy Award for Most Popular Foreign Writer, an unprecedented achievement.

“I accompanied Kim to the Galaxy Award ceremony in October and I could definitely feel the hype surrounding her,” says Kim Hak-je, lead editor of Hubble, the publisher of If We Cannot Move at the Speed of Light.

“In China, the majority of science fiction readers are male. But the organising committee said Kim opened the door for female readers. They seem to appreciate how Kim’s stories are focused on humanity compared with many other books that place emphasis on scientific accuracy and thought experiments.”

Contemporary Korean fiction has been gaining popularity in China in recent years despite the ongoing diplomatic tension between Beijing and Seoul, arising from the latter’s 2016 decision to deploy a US Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system.

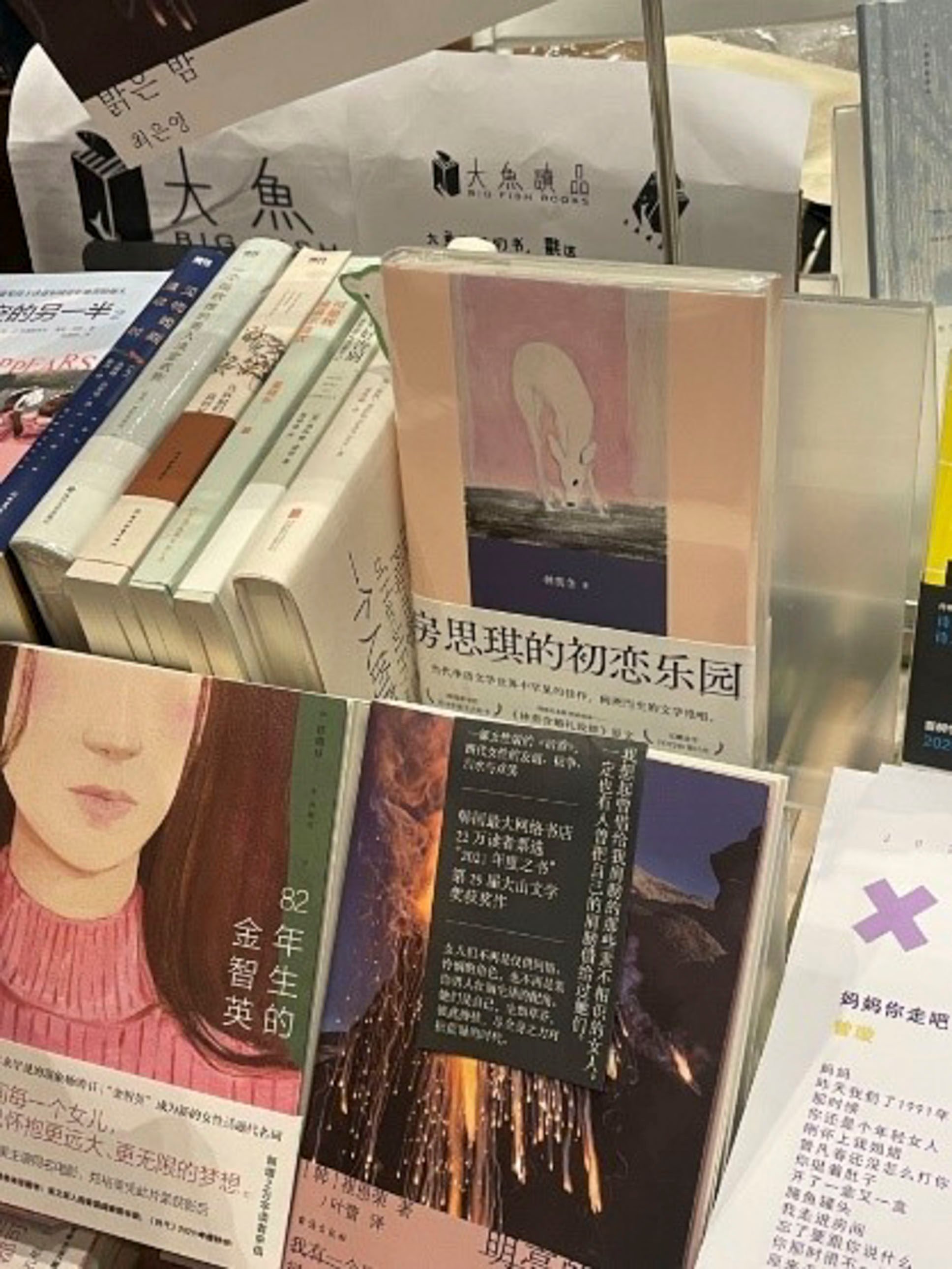

It started in 2019, when Cho Nam-joo’s Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 (2016) became a hit novel in China, prompting strong demand for translated Korean literature.

Ranked: the 15 best high-school Korean dramas of all time

Ranked: the 15 best high-school Korean dramas of all time

After coming out in September 2019, the book ranked No. 1 in sales on China’s leading online bookstore Dangdang. It has sold more than 300,000 copies and was republished in 2021.

With Chinese publishing houses today looking beyond books by award-winning or bestselling authors and being willing to collaborate with their Korean counterparts, it means that the profile of their writers is becoming more diverse, Kim Hak-je says.

Li Xia, who translated If We Cannot Move at the Speed of Light and writer and filmmaker Lee Chang-dong’s Nokcheon, says Korean literature is enjoying rising popularity because it deals with important social issues, such as feminism and challenges faced by young people today.

“From Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 to My Crazy Feminist Girlfriend by Min Ji-hyoung [published in May], Korea’s female writers and women’s literature have always captured Chinese readers’ attention,” Li says.

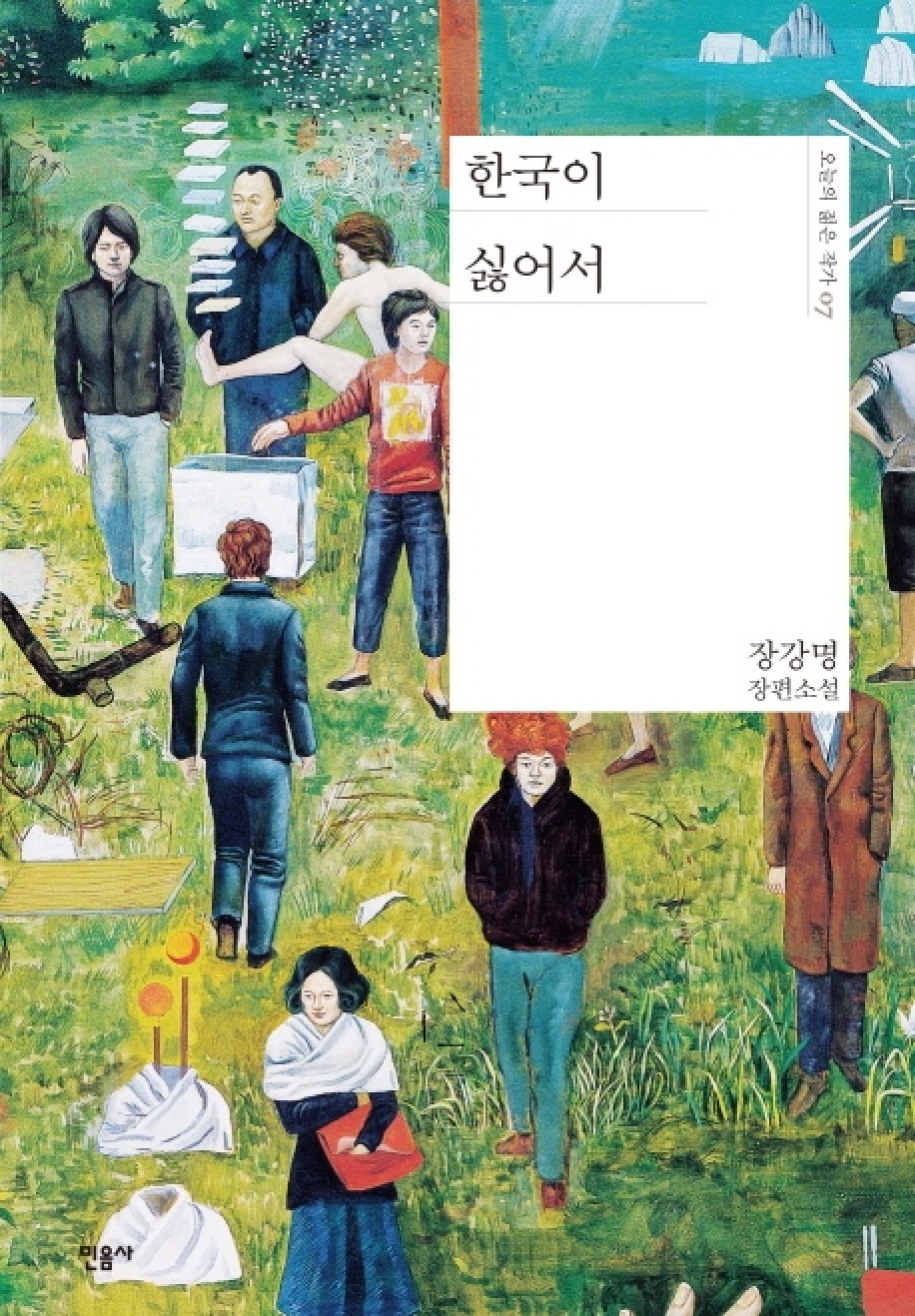

“Their popularity reflects a surge of interest in women’s rights, saying no to marriage and parenthood. Because I Hate Korea by Chang Kang-myoung resonated with many Chinese readers because it tackles universal themes by portraying the sufferings of young people.

“Apart from them, we are now seeing a growing interest in the science fiction genre thanks to Korean writers who took part in the 2023 Chengdu World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon) in October.”

The success of Korean literature in China may also be a knock-on effect of the country’s overall increased interest in Korean culture.

“The popularity of K-dramas, K-pop and Korean movies has led to a growing interest in Korean literature,” says Sophia Bae, a PhD candidate of art management and cultural industries at Peking University, and China coordinator for the Publication Industry Promotion Agency of Korea.

“The Chinese publisher of Kim Ji-young, Born 1982 promoted the book as the original book that was adapted as a film starring Gong Yoo.

“For Uncanny Convenience Store by Kim Ho-yeon, the Chinese publisher promoted it as the next heartwarming story about community following hit drama Reply 1988.

“Cocktail, Love, Zombies by Cho Yae-eun became popular among readers who enjoyed watching zombie thriller Train to Busan and zombie series All of Us Are Dead.”

Because young women in their 20s and 30s are the main consumers of Korean cultural content, most Korean literature fans are also female, Bae says.

She explains that Korean literature addressing social issues and reflecting contemporary concerns makes up a large part of the appeal for Chinese readers.

Bae notes there were only four or five Chinese publishing houses that sold translated Korean literature before 2019, including Jiangsu Literature and Art Publishing House, Beijing United Publishing, People’s Literature Publishing House and Citic Press Group.

Since 2019, the number expanded as regional publishing houses got in on the action, and now there are about 30-45 publishers that publish Korean books.

A lot of Chinese readers know about Korean literature, so it’s about time to prove what makes Korean literature special

Ye Mengyao has long been a K-drama superfan. But it was not until six years ago that she became fascinated with Korean literature.

“In 2017, there was a K-drama called Chicago Typewriter and Park Wan-suh’s Who Ate Up All the Shinga? appeared in the series. At that time, I realised I had never read Korean literature before. So I did some research and shared my thoughts on my personal Weibo account,” she says.

Since then, she began to read Park’s other works, as well as books by acclaimed Korean writers including Kim Young-ha, whose 2013 novel How a Murderer Remembers was adapted into a movie; Han Kang, whose 2021 novel I Do Not Bid Farewell won France’s Prix Medicis for foreign literature this year; and Cheon Myeong-kwan, whose 2004 novel Whale was shortlisted for the 2023 International Booker Prize.

With an aim to share the latest news on Korean books translated into Chinese, Ye started a public account called “GoodbyeLibrary” on Weibo and WeChat in 2019.

She shares news and updates of events related to Korean literature, publication schedules, and books that are looking for translators. Her account has over 17,000 followers on Weibo.

“[Chicago Typewriter] totally changed my life. I was meant to be a doctor and I have all the certificates to work as a doctor. But now, I work at a publishing house in Shanghai,” the 30-year-old says, adding she has read over 150 works of Korean fiction in Chinese.

According to Ye, the number of books translated from Korean to Chinese and published in China has been increasing over the past three years. In 2021, only nine Korean novels were translated into simplified Chinese; in 2022, the number increased to 24; and in just the first three-quarters of 2023, it had gone up to 37.

To increase the visibility of Korean literature in China, translator Li says Korea should start thinking about its market positioning and whether it wants to be remembered simply as a source of trendy books on Korean popular culture (hallyu), or also for books with more literary merit.

“A lot of Chinese readers know about Korean literature, so it’s about time to prove what makes Korean literature special,” she says.